It was another case of “so near, yet so far” for Brighton and Hove Albion last season, as the Seagulls missed out on automatic promotion to the Premier League only on goal difference, while a spate of untimely injuries led to defeat in the play-off semi-finals by Sheffield Wednesday, who had finished a full 15 points behind them in the league table.

Chairman Tony Bloom captured the feelings of the Albion fans: “The 2015/16 season was one of the most remarkable and exciting in my 40 years as a Brighton and Hove Albion supporter. The team, under Chris Hughton’s astute leadership, gave us a season to savour – and although we twice missed out on taking that final step to the Premier League, it has laid the foundation for our current season.”

This is the third time in the last four seasons that Brighton have reached the Championship play-offs, only to fall in the semis. This consistency on the pitch is all the more impressive, as it has been achieved under different managers: Guy Poyet in 2013; Oscar Garcia in 2014; and Hughton last year. The only blip came in 2015, when the club slipped back under the far-from-flying Finn Sami Hyypia.

"Many Happy Returns"

Of course, for those with longer memories it is great news that Brighton are still around to mount a challenge, given that they only avoided dropping out of the Football League to the Conference by the skin of their teeth in 1997 with a final day 1-1 draw at Hereford United.

There then followed years of struggle, exacerbated by the problems of finding a suitable ground after the Goldstone was sold to property developers, leading to exile in Kent and a ground share with Gillingham. The club returned to Brighton two years later to the Withdean, an old council-owned athletics stadium where the facilities were far from ideal.

It took 12 years, but finally Brighton moved to the magnificent new Amex stadium in 2011, coinciding with promotion to the Championship. The major investment required to build the stadium (and indeed a superb new training centre) was funded by Bloom, a lifelong fan who became chairman.

He has continued to finance the club, as can be seen by the 2015/16 accounts, which revealed a massive £25.9 million loss, £15.4 million worse than the previous season’s £10.4 million loss. To put that into perspective, that means that Brighton lost more than £2 million a month or around £500,000 every week.

The club said that this underlined Bloom’s commitment and in particular the ambition to reach the Premier League, while the chairman himself explained the strategy: “Our increased losses result directly from an ongoing and growing investment in our playing squad.”

This explains the main reasons for the higher loss, as wages shot up £6.7 million (33%) from £20.6 million to £27.4 million, while player amortisation (the annual cost of transfer fees) also rose £1.4 million (60%) from £2.4 million to £3.8 million. Moreover, the desire to retain players meant that profit from player sales fell £7.5 million from £8.7 million to just £1.2 million.

In addition, other expenses also increased by £1.1 million (7%) from £15.0 million to £16.0 million, largely due to higher costs associated with running the stadium.

The sizeable cost growth more than offset the £1.0 million (4%) increase in revenue from £23.7 million to £24.6 million, mainly due to broadcasting income rising £0.9 million (18%) to £5.9 million, though commercial income was also up £0.5 million (8%) to £9.4 million, driven by catering and events. On the other hand, gate receipts fell £0.4 million (4%) to £9.4 million, primarily due to no home cup ties.

Other operating income was up £0.4 million, thanks to other grants received.

In fairness to Brighton, almost all clubs in the Championship lose money and are reliant on owners’ funding. In 2014/15, the last season where all clubs have published their accounts, losses were reported by 18 of the 24 clubs – in stark contrast to the Premier League where the new TV deal, allied with wage controls, has led to a surge in profitability.

The club that made most money in the Championship that season were Blackpool – and their model is not one to be recommended, as it culminated in relegation to League One. As Bloom noted, “Any Championship club without parachute payments wishing to compete for promotion will inevitably make significant losses.”

That said, Brighton’s loss of £26 million in 2015/16 is likely to be one of the highest in the division. Only two clubs reported higher deficits in 2014/15: Bournemouth £39 million, though their loss was inflated by £9 million promotion payments and an £8 million fine for failing Financial Fair Play (FFP); and Fulham £27 million, but this was impacted by £11 million of exceptional impairment charges.

Brighton could have reduced their loss by accepting some of the lucrative offers received for their top talents, but Bloom noted that the club made a conscious decision “to retain our key players” and “not to cash in on our key assets”.

Consequently, there were no significant player disposals in the 2015/16 season, leading to only £1.2 million profits, probably driven by additional clauses from earlier player sales, as the contingent receivables on transfers have fallen from £2.1 million to £0.8 million in the latest accounts. In comparison, £8.7 million was booked in the previous season, mainly from the sales of Leo Ulloa to Leicester City and Will Buckley to Sunderland.

Although Championship clubs rarely sell players for big bucks, at least compared to the Premier League, this was a useful money-spinner for Brighton in 2014/15 with only four clubs generating more money from this activity. In contrast, the 2015/16 profit of just over £1 million is likely to be one of the smallest in the division.

Of course, losses are nothing new for Brighton. In fact, the last time that they made a profit was back in 2007/08 – and that was less than £1 million and only arose because of a £3.6 million exceptional credit, due to a change in the accounting for the Falmer stadium expenses. Since then, the club has made cumulative losses of £88 million.

Moreover, the losses have been growing. Since promotion to the Championship, Brighton’s total losses have amounted to £71 million, averaging £14 million a season. As finance and operations director David Jones confirmed, “We’ve lost money every year we’ve been (at the Amex).”

Jones added, “While we’re getting a competitive team on the pitch, we’re going to continue to lose money with the revenue streams that we’ve got.” The difference with the top flight is colossal. Jones again, “If we were in the Premier League, we would be able to be a sustainable business that makes an annual profit.”

If they are not promoted, it will be interesting to see what the board decides regarding player sales. Traditionally Brighton have made very little from the transfer market , though there was a change in stance in 2013/14 when the club sold Liam Bridcutt to Sunderland and Ashley Barnes to Burnley, followed by the even more profitable sales in 2014/15.

This summer Brighton could have made a lot of money if they had accepted all the offers they received, e.g. Dale Stephens (Burnley), Lewis Dunk (Fulham) and Anthony Knockaert (Newcastle United). That could have brought in £15-20 million, though obviously would have damaged Brighton’s prospects of promotion.

The current strategy is to “speculate to accumulate”, but as Bloom has admitted, “It would be ridiculous for me or any owner to say that a player is never for sale. There’s always a price for any player.”

Brighton’s strategy is more clearly seen by the club’s alternative presentation of the profit and loss account, which highlights the 29% (£7 million) increase in the football budget in 2015/16.

Chief executive Paul Barber, who has overseen a “pretty radical and dramatic programme of reducing our costs” explained the approach as follows “It gives us more opportunity to put more into the football budget, which should improve our chances of promotion.”

In this way, administrative and operational costs have been cut by 22% since 2012, which has meant that Brighton’s different managers have benefited from a significant increase in the football budget over this period of around 134%, as it has grown from £13 million to £31 million.

Bloom praised his team for “ensuring we remain operationally efficient”, but the reality is that Brighton’s underlying profitability has still been getting worse, as seen by the reduction in EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Depreciation and Amortisation).

This metric is considered to be an indicator of financial health, as it strips out once-off profits from player trading and non-cash items. It has been consistently negative at Brighton, but has declined in the last eight years from minus £3 million in 2008 to minus £18 million in 2016.

Unsurprisingly, a negative EBITDA is far from uncommon in the Championship with 21 clubs generating cash losses, though only Nottingham Forest have worse underlying figures than Brighton. In stark contrast, in the Premier League only one club reported a negative EBITDA, which is again testament to the earning power in the top flight.

Brighton’s revenue surged from £7.5 million in 2011 to £24.6 million in 2016 following promotion from League One to the Championship, exacerbated by what can be described as the "Amex effect" with gate receipts being more than four times as much as Withdean, increasing from £2.3 million to £9.4 million.

In addition, the new stadium has brought more commercial opportunities, leading to income climbing from £3.1 million to £9.4 million. The club could negotiate better deals with sponsors in the higher division (up from £0.8 million to £5.5 million), increase retail sales, e.g. from the stadium megastore (up from £0.5 million to £1.3 million) and make more from catering, i.e. pies and the famous Harveys beer (up from £35k to £1.3 million).

However, the growth since the first season back in the Championship in 2012 is less impressive, amounting to just 11% (£2.5 million) in four years. The fact is that it is difficult to substantially grow revenue streams without another promotion to the top flight.

Brighton’s revenue of £25 million places them around 7th highest in the Championship, but the clubs with the three highest revenues in 2014/15 (Norwich City, Fulham and Cardiff City ) were more than 60% higher with £40-52 million.

Bloom is acutely aware of the challenge this poses: “Our player budget is the highest it has ever been, so we have certainly invested, but we absolutely can't compete financially with relegated clubs like QPR, Burnley and Hull with their parachute payments.”

He’s not wrong, as two of the three clubs he named were promoted back to the Premier League last season, once again proving that money talks in football. Jones reiterated his chairman’s message, noting that this factor “presents difficulties when trying to assemble a playing staff that can compete with clubs coming down from the Premier League, whose TV parachute payments can inflate their revenue to around £40 million.”

Excluding the impact of the parachute payments made to those clubs relegated from the Premier League (£26 million in first year after relegation) Brighton’s revenue would be one of the highest in the Championship. This season the disparity between “the haves and the have nots” will be even larger, as the relegated clubs include Newcastle United and Aston Villa.

Even Chris Hughton has commented on this hurdle, when discussing Newcastle: “They’ve come down with parachute payments, they are a massive club and they are doing their very best to make sure they go straight back up again.”

The majority of Brighton’s revenue comes from the stadium with gate receipts contributing 38%, up from 30% at Withdean, though this is only just ahead of commercial income 38%, following the relatively higher growth rate in the last few seasons. Broadcasting is up to 24%, though this is much lower than the Premier League, where TV money accounts for 70-85% of total revenue at half the clubs.

Clearly, Brighton are more reliant on match day income than most. In fact, in 2014/15 only two clubs were more dependent on this revenue stream: Nottingham Forest and Charlton Athletic.

Despite improved results on the pitch, gate receipts fell for a second consecutive season, decreasing 4% (£0.4 million) from £9.8 million to £9.4 million, largely due to a lack of home cup ties.

Nevertheless, this is still likely to be the highest match day revenue in the Championship in 2015/16, as the only team ahead of them in 2014/15 was Norwich City, who were promoted to the Premier League last season. It will be another story this year, due to the arrival in the second tier of Newcastle and Villa with their large crowds.

Average attendance slipped slightly from 25,640 to 25,583, partly due to the knock-on impact of the disappointing 2014/15 season, but this was still the second highest in the Championship, only surpassed by Derby County 29,663, though ahead of all three promoted clubs: Middlesbrough 24,627, Hull City 17,199 and Burnley 16,709.

Since the move to the Amex, attendances had been steadily rising from the 7,352 at Withdean, as the new stadium finally met latent local demand for tickets. Brighton’s potential has been highlighted this season by three games selling out (Norwich, Villa and Fulham). In fact, the club has in excess of 22,000 season ticket holders and 1901 Club members.

Ticket prices are among the highest in the Championship. According to the BBC’s Price of Football survey, Brighton has the second highest cheapest season ticket (only below Norwich) and the third highest most expensive season ticket (behind Ipswich and Fulham). However, the survey did note that tickets include a travel subsidy to and from the ground for fans by public transport or use of the park-and-ride option, valued at £4 per game for adults.

It is also worth mentioning that Brighton supporters are happier with their match day experience than any others according to a Football League study, partly due to the magnificent facilities that are second to none, including free wi-fi and VIP padded seats. The club is also good to away fans, lighting the concourse in their colours and having their local beer on tap. The only fly in the ointment is the appalling “service” from the dreaded Southern Rail.

The good news is that the club froze most ticket prices in 2015/16 and have restricted price rises in 2016/17 to no more than a couple of pounds per match. Barber said this was to reward fans for “the ongoing loyalty and support they’ve shown to the club.”

Brighton’s broadcasting revenue rose 19% (£0.9 million) from £4.9 million to £5.9 million in 2015/16, which was attributed to an increase in the Football League basic distribution plus the club being shown more times on live TV.

In the Championship most clubs receive the same annual sum for TV, regardless of where they finish in the league, amounting to around £4 million of central distributions: £2.1 million from the Football League pool and a £2.3 million solidarity payment from the Premier League. There are also payments for each live TV game: £100,000 home; £10,000 away.

This might not sound much, but Barber argued, “TV income is extremely important for all clubs, including ours”, adding, “without revenue from Sky TV, ticket prices would go up.”

However, the clear importance of parachute payments is once again highlighted in this revenue stream, greatly influencing the top nine earners in 2014/15. Nevertheless, it should be noted that these payments are not necessarily a panacea, e.g. Middlesbrough secured promotion last season, even though their broadcasting income of £6 million was less than half the size of those clubs boosted by parachutes.

Looking at the television distributions in the top flight, the massive financial chasm between England’s top two leagues becomes evident with Premier League clubs receiving between £67 million and £101 million in 2015/16, compared to the £4 million in the Championship. In other words, it would take a Championship club more than 15 years to earn the same amount as the bottom placed club in the Premier League.

The size of the prize goes a long way towards explaining the loss-making behaviour of many Championship clubs. This is even more the case with the new TV deal that started in 2016/17, which Barber described as “astonishing”. This will be worth an additional £35-60 million a year to each club depending on where they finish in the table.

Even if a club were to finish last in their first season in the top flight and go straight back down, their TV revenue would increase by an amazing £95 million. They would also receive a further £71 million in parachute payments, giving additional funds of around £166 million. If they survived another season, you could throw in another £120 million.

Of course, if they did go up, Brighton would also have to spend more to strengthen their playing squad, but the net impact on the club’s finances would undoubtedly be positive, as evidenced by the improvement in the bottom line for those clubs promoted in the past few seasons.

As we have seen, parachute payments make a significant difference to a club’s revenue and therefore its spending power in the Championship. From this season, these will be even higher, though clubs will only receive parachute payments for three seasons after relegation. My estimate is £83 million, based on the percentages advised by the Premier League: year 1 – 55%, year 2 – 45% and year 3 – 20%.

The other point worth emphasising is that if a club is relegated after only one season in the Premier League, it will only benefit from parachute payments for two years.

There are some arguments in favour of these payments, namely that it encourages clubs promoted to the Premier League to invest to compete, safe in the knowledge that if the worst happens and they do end up relegated at the end of the season, then there is a safety net. However, they do undoubtedly create a significant revenue disadvantage in the Championship for clubs like Brighton.

Commercial income grew by 5% (£0.5 million) from £8.9 million to £9.4 million, comprising commercial sponsorship and advertising £5.5 million, catering and events £1.3 million, retail £1.3 million, academy grant £0.9 million, other income £0.3 million and women and girls £0.1 million. The main driver for the growth was a £0.4 million increase in catering and events, primarily as a result of the Rugby World Cup matches hosted at the Amex.

In the new world of FFP, Bloom has said that the club “had to adapt and move quickly to establish a sharper commercial focus. We had to focus on the inherent value of our brand.” The club’s success in this area is reflected by Brighton having one of the highest commercial revenues in the Championship, only behind Norwich City and Leeds United in 2014/15.

This is despite the fact that Brighton now only report the net catering commission in revenue, whereas in previous seasons all the gross revenue was included in revenue with the expenses shown in costs.

"Back on the Shane gang"

What has been particularly impressive in recent years is the increase in sponsorship, though it remained static in 2015/16, largely due to the contractual cycles. American Express are not only shirt sponsors, but also naming rights partner for the stadium and the training ground. This multi-year agreement, signed in March 2013, was described by Barber as “the biggest in the club’s history.”

Similarly, Barber said that the 2014/15 Nike deal, replacing Errea after 15 years as the club’s kit supplier, represented “a significant increase on our existing commercial arrangement.”

Interestingly, the club has applied for planning permission for a 150 room hotel alongside the stadium, though the City Council has to date rejected the application. Barber said that this “would have been a valuable addition to our non-matchday revenue.” They remain “hopeful of a successful outcome”, which is just as well as they have to date spent over £2 million on this development.

Brighton’s wage bill shot up by 33% (£6.7 million) from £20.6 million to £27.4 million in 2015/16, “in order to be as competitive possible and give ourselves the best possible chance of success on the pitch.” This would have included high wages for the returning Bobby Zamora, even though he arrived on a free transfer.

It is worth noting that since 2012, the first year back in the Championship, the wage bill has grown by £12.7 million (87%), while revenue has only increased by £2.5 million (11%).

This is all seen on the pitch, given the significant reduction in administrative and operational expenses. For example, in 2015/16 the number of players rose from 61 to 73, while other staff were flat at 197.

Despite this growth, Brighton’s £27 million wage bill is still only the eighth highest in the Championship, so promotion would indeed be a fine achievement. As a comparative, the top three in the Championship in 2014/15 were Norwich City £51 million, Cardiff City £42 million and Fulham £37 million.

Barber understands this challenge: “We haven’t got anywhere near the biggest budget in the division. We’re probably 10th or 11th. So we’ve had to spend wisely, and eke out every ounce of value from every deal.”

That said, it would be no surprise if Brighton’s wage bill further rose this season, as they have been extending contracts for a number of important individuals, including Hughton, Beram Kayel, Solly March and Conor Goldson, though this will ensure a decent price if they are sold.

The remuneration for the highest paid director, who is not named, but is surely Paul Barber, has increased from £558k to £578k. This is a lot of money, but Barber is really a Premier League level chief executive, who has been pretty successful in cutting operational expenses and renegotiating many of the sponsorships.

Brighton’s wages to turnover ratio increased (worsened) from 87% to 111%, the highest since 2009 when the club was in League One. This is not exactly great, but it is by no means one of the highest in the Championship. In 2014/15 no fewer than 11 clubs “boasted” a wages to turnover ratio above 100% with the worst offenders being Bournemouth 237%, Brentford 178% and Nottingham Forest 170%.

The (relatively) prudent approach is evidently the one that Brighton want to follow, especially in a FFP world, as noted by Bloom: “While we do want to play at the highest level, we cannot simply open our cheque book and start spending without care or attention.”

Other expenses rose by 7% (£1.1 million) from £15.0 million to £16.0 million, which is by far the highest in the Championship, ahead of Fulham £13.4 million and Leeds United £12.6 million.

This is the other side of the coin of moving to the Amex, as this year’s increase was largely due to stadium expenses: maintenance, running costs and security. There are also some costs that are exclusive to Brighton, as Barber note, “The contribution that the club makes to the cost of travel has grown, meaning that we have a large seven-figure transport bill that other clubs don’t have.”

Non-cash expenses have also been on the rise with depreciation and player amortisation increasing from just £237k in 2009 to £8.7 million in 2016, reflecting the club’s investment in infrastructure and the playing squad.

In 2015/16 depreciation was unchanged at £4.9 million, which is more than twice as much as any other club in the Championship, the next highest being Derby County £2.1 million. This represents the annual charge of writing-off the cost of the stadium and the training ground. These are depreciated over 50 years, i.e. 2% of cost per annum.

Player amortisation was 60% (£1.4 million) higher at £3.8 million, following the strengthening of the squad, but this not out of the norm in the Championship. The highest player amortisation in 2014/15 was found at clubs recently relegated from the Premier League, namely Norwich £13 million, Cardiff £11 million and Fulham £11 million.

However, to place this into perspective, even these clubs are miles behind the really big spenders in the top tier like Manchester City (£94 million) and Manchester United (£88 million). This is partly because there is no amortisation required for those players who have been developed at the Academy, e.g. Dunk and March in Albion’s case.

The accounting for player trading is fairly technical, but it is important to grasp how it works to really understand a football club’s accounts. The fundamental point is that when a club purchases a player the transfer fee is not fully expensed in the year of purchase, but the cost is written-off evenly over the length of the player’s contract, e.g. Irish international defender Shane Duffy was bought from Blackburn Rovers for a reported £4 million on a four-year deal, so the annual amortisation in the accounts for him is £1 million.

Over the years, Brighton have not been a big player in the transfer market, often registering net sales, though they have increased their gross spend recently, averaging £5.6 million in the last two seasons, compared to just £0.9 million over the previous nine seasons.

It is striking that there have been no meaningful sales in this period, as Barber explained, “Our key objective this summer was to retain our best players which, despite a lot interest and a number of offers for different players in our squad, we have managed to do.”

They also wanted to strengthen the squad in key areas this summer, so recruited Shane Duffy and Oliver Norwood, who made a good impression at the Euros with the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, and the returning Steve Sidwell. They have also made good use of the loan market, bringing in prolific goal scorer Glenn Murray from Bournemouth and full-back Sebastien Pocognoli from West Brom.

"A French Kiss in the Chaos"

Last season they also bought well with Anthony Knockaert, Tomer Hemed, Jiri Skalak, Conor Goldson, Liam Rosenior, Jamie Murphy, Gaetan Bong and Uwe Hünemeier all making decent contributions.

However, it is apparent that Brighton have not gone overboard in terms of spending, especially compared to some of their principal rivals who are really “going for it”. To illustrate this, in the last two seasons Brighton had net spend of 11 million, while they were comfortably outspent by Derby County £26 million, Norwich City £23 million and Sheffield Wednesday £21 million.

Not to mention Aston Villa and Newcastle United who have somehow found themselves in the Championship despite substantial net spend of £47 million and £43 million respectively. As Hughton said, “There are big spenders in this division. We can’t compete with what Newcastle and Aston Villa are doing. What we have done has been sensible.”

Therefore, Brighton have to box clever, as Bloom explained: “There are other clubs in the division who have spent significantly more than us. So we just have to make sure we recruit smarter and that the team dynamic overcomes the financial disadvantage we've got against certain other clubs.”

Although holding onto players was clearly the strategy for this season, Bloom recently indicated at a fans’ forum that things might be different next season, so this may well be Brighton’s best opportunity to get promotion.

Brighton’s net debt rose by £25.6 million from £140.5 million to £166.1 million with the £23.0 million increase in gross debt to £170.6 million compounded by cash falling by £2.6 million to £4.5 million.

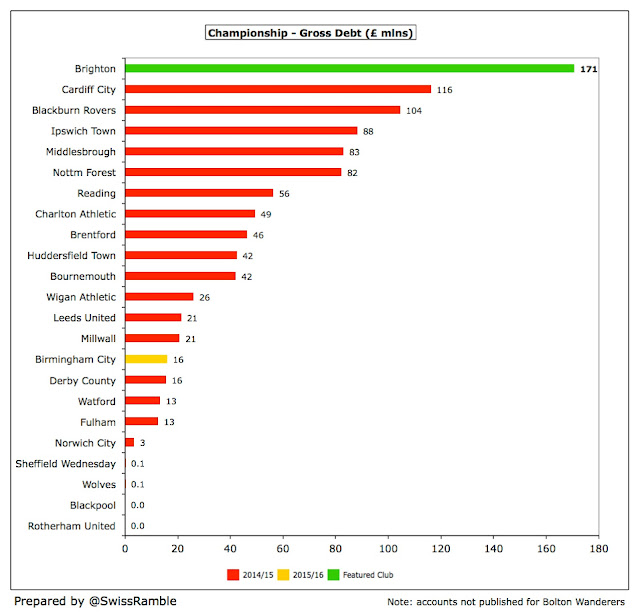

Debt has been rising over the past few years, so much so that Brighton now have the largest debt in the Championship, substantially more than other clubs, e.g. Cardiff City £116 million, Blackburn Rovers £104 million and Ipswich Town £88 million. However, it is entirely owed to Bloom, is interest-free and can be regarded as the friendliest of debt.

The cash flow statement reveals that Bloom has also converted £22 million of loans into share capital, including £11 million in 2015/16, which means that Bloom actually stumped up £34 million last season. Furthermore, since the accounts were published, he converted an additional £8 million of loans into shares, i.e. a running total of £30 million.

Adding the £80 million that Bloom has funded via share capital (including the debt conversions) to the £171 million of debt means that Bloom has put in a total of £251 million – that’s a cool quarter of a billion.

Just pause to let that sink in for a moment. One. Quarter. Of. A. Billion. Pounds.

As David Jones commented, “That’s a massive amount of money for an owner to have to subsidise a club for. And when you consider we’ve got one of the highest two or three attendances in the Championship, some of the best sponsorship deals, we’re still needing the owner to help us with that kind of subsidy. It’s substantial.”

Looking at how Brighton have used these funds since Bloom took charge, the majority (£155 million) has gone on investment into infrastructure (including £103 million on the stadium and £32 million on the training centre), while £83 million has been used to bankroll operating losses. Hardly any money was spent on new players in this period with a net outlay of less than £5 million.

There were a couple of interesting corporate actions after the accounts closed. Authorised share capital was doubled from £100 million to £200 million – potentially paving the way for a significant debt conversion? In addition, the club created £40 million of Convertible Unsecured Loan Notes.

Being so dependent on one individual can be a concern, but Bloom comes from a family of Brighton supporters: “I have absolutely no intention of selling. I think I will be here for many years to come.”

"Hands Held High"

He continued: “Our ambition remains for the club’s teams, both men and women, to play at the highest level possible – and as chairman (and a lifelong supporter of the club) I will do everything I possibly can to achieve that and I remain fully committed to that goal.”

Bloom is seriously wealthy from his property and investment portfolio (plus money earned from poker and other forms of gambling), but Brighton are very fortunate to have such a generous benefactor.

As Jones said, “If you’re an ambitious Championship club and you don’t have the benefit of parachute payments, then you’re going to need an owner that’s prepared to subsidise you substantially.”

"Sound Czech"

However, Bloom would not be able to simply buy success, even if he wanted to, as Brighton need to follow the Football League’s FFP regulations. Under the new rules, losses will be calculated over a rolling three-year period up to a maximum of £39 million, i.e. an annual average of £13 million, assuming that any losses in excess of £5 million are covered by owners injecting equity (hence the £8 million debt conversion in July 2016).

These limits are much higher than the previous £6 million a season, so are likely to encourage clubs to spend even more, making the division even more competitive.

Brighton have confirmed that they will comply with these rules in 2015/16 (“as we have done each season”), which might seem strange, given that the reported £26 million loss was twice the £13 million limit.

"Another Dale in my heart"

This is because FFP losses are not the same as the published accounts, as clubs are permitted to exclude some costs, such as depreciation, youth development, community schemes and any promotion-related bonuses.

Brighton’s depreciation was £5 million, which implies that they have spent £8 million on their academy and the community in order that the FFP loss was lower than the £13 million limit in 2015/16. Even though these activities represent a major investment for the Albion, it seems unlikely that the expenditure would be that high, but it is difficult to see how else the club could have complied.

Going forward, the assessment is calculated over a three-year period, which means that a higher loss one year can be compensated in later years, e.g. via player sales, or might even become irrelevant (if the club is promoted).

Either way, Bloom was right when he said it is “a delicate balancing act for the board, as we strive to achieve our ultimate aim.”

"Spanish Steps"

The last time Brighton were in the top flight was way back in 1983, but this club is clearly ready for the Premier League. As Bloom said, “That’s what we built the stadium for, that’s what we built our magnificent training ground for.”

Bloom appears just as happy with the situation on the pitch: “To compete at the top end of the Championship, it’s important to have a manager who knows how to win at this level and to possess a strong group of quality players. We have both, and while this doe not guarantee promotion, it gives us an excellent chance.”

Given what happened last season, nobody at the Amex is taking anything for granted. Barber spoke for everyone: “We’ve made a really strong start. But we also know that this is the toughest division in the world and that nothing has been achieved at this point.”