Despite their failure to reach next month’s Champions League final, Barcelona and Real Madrid are by common consent the best two club sides in world football. Featuring superstars such as Lionel Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo, their talented players entertain and delight us in equal measure, as they dominate La Liga season after season.

However, admiration of their exploits is tempered by the financial advantages that they enjoy compared to other less fortunate clubs. Not only do they generate far more revenue than anybody else (around €100 million higher than the nearest challenger, Manchester United), but one of the main reasons for this substantial competitive advantage is an unbalanced domestic TV deal that awards the two Spanish giants almost half of the money available.

Their reputation off the pitch also suffered a hit recently in the media when it was “revealed” that these great teams were built on a mountain of debt (€590 million at Real Madrid and €578 million at Barcelona), raising questions as to whether this was, to coin a phrase, “financial fair play.”

Quite why this came as a surprise to some analysts is a little perplexing, given that the clubs’ accounts have been available to the public for many months. Whatever.

"Pep Guardiola - Goodbye cruel world"

The fundamental issue is whether this debt is too high, as many commentators suggest, with the implication that these grand old clubs might even be in some financial difficulty.

That might seem like an easy question to answer, but, as is so often the case in the murky world of accounting, it’s not quite so simple. To give a comprehensive response, we have to do three things:

1. Importantly, understand what this debt figure actually represents, as there are numerous definitions, all of which can be equally valid in different circumstances.

2. Look at the overall strength (or weakness) of each club’s balance sheet, i.e. also at assets, not just liabilities.

3. Explore how well the debts are covered by items such as income and cash flow.

To avoid looking at Madrid and Barcelona in isolation, we should also compare their debt position with that at other leading clubs. For the purpose of this exercise, I have opted to look at two English teams, Manchester United and Arsenal, as they are useful comparatives, who are viewed as being at different ends of the spectrum. The former are known for the large amount of debt they have been carrying since the Glazers bought the club via a leveraged buy-out, while the latter are often portrayed as the poster boy of sustainable football clubs.

"Jose Mourinho - I couldn't bear to be special"

1. What is debt?

For people without a financial background, the different definitions of debt can be a bit confusing, as acknowledged by UEFA’s snappily titled Club Licensing Benchmark report, which stated, “In practice, the term ‘football club debts’ has been used in many different ways with a great deal of flexibility, references ranging from the very broad, totalling all liabilities that a club has, to the narrow definition of debt financing either including or excluding interest-free owner loans.”

At the narrowest extreme, we have just bank debt: at the broadest extreme, we can use total liabilities, which covers all financial obligations, including tax liabilities, trade creditors, provisions for future losses, accrued expenses and even deferred income. Often, when the media refer to debt, they actually mean total liabilities.

This includes what might be described as operational debt, such as: (a) trade creditors (payables) for amounts outstanding on bills for products or services received, e.g. rent, electricity; (b) money owed to staff, e.g. wages earned by staff paid at the end of the month, bonus payments; (c) other accrued expenses (accruals), which are the same as payables except no invoice has yet been received; (d) provisions, which are an estimate of probable future losses, e.g. legal claims; (e) and, most bizarrely, deferred income for payments received for services not yet provided, e.g. season ticket revenue for matches to be played in the future.

That last one highlights one danger of using liabilities as a definition for debt, as season ticket money received in advance is clearly not a bad thing, as UEFA explain: “It is recorded as a liability, as accountants consider the cash received as not yet being fully earned until the matches take place. This is a liability, but not a debt that will have to be paid back.”

So, much of Madrid’s €590 million and Barcelona’s €578 million debt includes liability for what might be termed normal operations. If we apply the same definition to Manchester United, they have debt (total liabilities) of just under €1 billion (£824 million converted at a rate of 1.20). Even Arsenal’s debt on the same basis is €524 million, which the journalists would no doubt describe as “eye-watering” if they were talking about others and not their template for a well-run club. To use an old adage, you have to make sure that you are comparing apples with apples.

Of course, if you wanted to make a club’s debt look as bad as possible, then you would absolutely use the total liabilities definition. However, it is very conservative to say the least. Indeed, in response to their critics, Madrid and Barcelona might feel like misquoting Mark Twain: “The reports of my debt have been greatly exaggerated.”

The net debt reported in an English club’s financial statement will be in line with IFRS (International Financial Reporting Standards) and essentially covers purely financial obligations, such as overdrafts, bank loans, bonds, shareholder loans and finance leases less cash. On this basis, the gross debt of Madrid and Barcelona at €146 million and €150 million respectively is not only considerably smaller than the figure highlighted in the press, but is also much lower than Arsenal €310 million and Manchester United €551 million.

The difference is not quite so large for net debt, as both United and Arsenal have substantial cash balances, but the Spanish clubs are still lower: Madrid €48 million and Barcelona €89 million. Arsenal are much of a muchness with €117 million, while United are the outlier with a hefty €370 million.

In their Financial Fair Play (FFP) guidelines, UEFA introduce a third definition of debt which lies somewhere between the narrow calculation employed in annual accounts and the widest possible measure of total liabilities: “A club’s net player transfers balance (i.e. net of accounts receivable from players’ transfers and accounts payable from players’ transfers) and net borrowings (i.e. bank overdrafts and loans, owner and/or related party loans and finance leases less cash and cash equivalents).”

They go on to explicitly state, “Net debt does not include trade or other payables.” However, it does include the net balance owed on player transfers, which is a reasonable approach to take, as this can be an important element in the business model adopted by some football clubs, e.g. this amounts to €76 million at Madrid (actually down from €111 million the previous year and an astonishing €211 million in 2009), though it is only €12 million at Arsenal, which probably comes as no surprise to those fans that have been exhorting the club to spend some money.

This has clearly been an important factor in allowing Madrid to finance big money acquisitions. Although all clubs make stage payments for transfers, very few do so to the same extent as Madrid (and indeed Barcelona).

Of course, this does not make the practice inherently wrong. Indeed, UEFA commented, “It is worth noting that the size of transfer payables reported in financial statements can be influenced by the timing of the financial year-ends relative to the timing of transfers, and that transfer payables are, in most cases, not overdue but in line with the payment schedule agreed between the respective clubs.”

Under this UEFA definition, it is remarkable how similar the net debt is between Madrid, Barcelona and Arsenal, with all three clubs reporting a balance in a narrow range of €124-131 million. The exception to the rule is United with, deep breath, €442 million.

2. Strength of the balance sheet

To state the blindingly obvious, liabilities are only one side of the story (or balance sheet). To get a full picture of a football club’s health, we also have to look at its assets. This is where the English clubs start to look better, as they tend to have higher assets, especially as they usually own their own stadiums.

United’s net assets (assets less liabilities) are a mighty €973 million, though €618 million of this is due to inter-company receivables from the parent undertaking, while Arsenal have a highly respectable €322 million. Madrid are far from shabby with net assets of €251 million, but Barcelona fall down on this measure with net liabilities (also described as negative equity) of €69 million. In other words, their reported liabilities are larger than their reported assets. Barcelona are far from alone in this, as UEFA’s benchmarking report noted that 36% of clubs reported negative equity in 2010, but it is still nothing to be proud of.

If this ratio is refined to only cover current assets and liabilities (payable within 12 months), then it is even worse for the Spanish clubs, as they both have net current liabilities: Madrid €141 million and Barcelona €226 million.

Once again, the accounting values are a little misleading when looking at the balance sheet, because of the way that certain assets are treated in the accounts. As UEFA say, “Some of the principal assets of a club, such as a loyal supporter base, reputation/brand, membership/access rights to lucrative competitions, and home-grown players, are not included within balance sheet assets since they are extremely difficult to value, despite them unquestionably having a value. These unvalued assets tend to be greater for larger clubs.”

"The Glazers - Money (that's what I want)"

This is highlighted when a football club is sold. Invariably, the purchaser pays a higher price than the fair value in the accounts and the difference is booked as an asset called goodwill. In this way, Manchester United’s balance sheet includes £421 million of goodwill.

This can also be seen very clearly with player valuations. In the accounting world, when a player is bought, football clubs do not expense the cost immediately, but instead book it onto the balance sheet as an intangible asset and write it off evenly over the length of the contract. Following the Bosman ruling, the assumption is that the player will have no value after his contract expires, since he could then leave on a “free”.

However, the value in the real world is almost always higher. As Javier Faus, Barcelona’s Vice President of Finance once explained, his club has over €250 million of assets that are not reflected in the balance sheet. This is particularly the case for the Catalans, as their team is full of players developed in-house by the legendary La Masia, and these effectively have zero value in the accounts. I don’t know exactly how much the likes of Messi, Xavi and Iniesta would be worth if sold, but I do know that it’s more than zero.

The respected Transfermarktwebsite does actually list values for each major team’s squad, so we can get an idea of how much stronger each club’s balance sheet would look if you applied real values instead of accounting values. As expected, this is most striking in the case of Barcelona, where the real value is estimated as €591 million, so €470 million higher than the books, leading to adjusted net assets of €401 million.

Of course, it would kind of defeat the object if a club were to realise that value by selling all its players, but a few judicious sales can make a big difference to the reported strength of a club’s balance sheet.

3. Debt coverage

As we said earlier, Real Madrid (€480 million) and Barcelona (€451 million) have the highest revenues in world football, covering around 80% of their debt, which is significantly higher than their English counterparts, Arsenal 57% and Manchester United 40%. In Arsenal’s case, this is obviously a function of much lower revenue (€307 million), even though I have included property income, as liabilities are not split by business segment.

However, as the old saying goes, “revenue is for vanity, profit is for sanity”, so a more useful ratio might be cash flow to debt, which provides an indication of a club’s ability to cover total debt with its annual cash flow from operations. There are many ways of defining cash flow, but I have used EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxation, Depreciation and Amortisation) for simplicity’s sake. Others might adjust for (irregular) profit on player sales, while you could also use free cash flow, (operating cash flow minus capital expenditure).

Contrary to popular belief, Real Madrid and Barcelona are relatively profitable: Madrid have made total profits of around €200 million in the last five years, including €47 million last season; while Barcelona’s loss was only €12 million. Adjusting for non-cash flow expenses like depreciation and amortisation plus interest produces very impressive EBITDA of €151 million for Madrid and pretty good €66 million for Barcelona. In the same way, Manchester United’s notable ability to generate cash results in excellent EBITDA of €138 million.

So, Madrid’s cash flow over debt ratio comes in at 26%, much better than the others: Manchester United 14%, Arsenal 13% and Barcelona 11%. Simply put, the higher the percentage, the better the club’s ability to pay its debt.

While it is clearly important to be able to ultimately pay off debt, a club’s ability to service its interest expenses is absolutely crucial. This can be explored with the interest coverage ratio (cash flow/interest payable), which tells a similar story to debt coverage, i.e. Madrid’s ratio of 11.7 is by far the best, though the others are not too bad: Barcelona 4.5, Arsenal 3.9 and Manchester United 2.5 (anything below 1.5 is a bit questionable).

What is striking here is just how much higher the interest payable is at United €56 million (£46 million) compared to the other clubs: Arsenal €18 million, Barcelona €15 million and Madrid €13 million. In fact, both “heavily indebted” Spanish clubs actually pay less interest than the two English clubs.

Let’s look at the debt in a bit more detail for the clubs we are reviewing, as this might throw up some other anomalies.

Real Madrid’s accounts use yet another definition for debt, which is essentially the same as UEFA’s definition (bank debt plus net transfer fees payable) plus selected creditors (essentially stadium debt). This gives a net debt of €170 million, a reduction of €75 million from the €245 million in 2010. That’s pretty impressive, especially when we consider that the net debt peaked at €327 million the year before.

That said, for many years before 2009 they had no bank debt at all. The loans are split evenly between Caja Madrid and Banco Santander and were mainly used to finance the major signings that summer. The interest rate is relatively low, but the loans do have to be repaid by 2015, though even here Madrid were given some leeway with lower payments in the first three years.

Stop me, if you’ve heard this before, but Barcelona also use a different definition for debt, providing their Annual General Meeting with a figure of €364 million, which is not fully explained, but the main distinguishing factor is that some debtors are deducted to arrive at the net balance.

This represents a 15% reduction from the €430 million reported the previous season, but is still higher than the preceding years. Indeed, Javier Faus, Barcelona’s Vice President of Finance, admitted, “We’ve reduced the debt, but we’re still in a delicate situation. The debt is still too high for us to be able to dictate our future. We can’t afford to owe so much money to the bank, and we need to generate more income.”

He emphasised the board’s concern when he added, “It’s not the debt that we want, and we have to reduce it further, to sustainable levels, with regard to the cash flow generated by the club. We’ll continue to work on it.” Ideally for Faus, the net debt would be “just over €200 million.”

Indeed, Barcelona were forced to take out syndicated loans of €155 million in 2010 from a group of banks led by La Caixa and Banco Santander, though club president Sandro Rosell has defended Barca’s debt level, arguing that it is eminently serviceable via its huge revenues, “The club is not bankrupt, because it generates income. The banks know that we have a business plan that will allow them to recover the money.”

Indeed, the willingness of Spanish banks to help Barcelona is a factor, as it is difficult to imagine a scenario where a local financial institution would be responsible for damaging the emblem of Catalonia, given that its customer base is largely made up of the club’s supporters – even with the struggles in the Spanish economy. This is evidenced by the banks ignoring Barcelona’s breach of commitments in terms of total liabilities made when securing the 2010 loan.

Manchester United have also succeeded in reducing their net debt, which was cut from £377 million to £308 million (£459 million gross debt less £151 million cash), after the club bought back £64 million of its bonds. This is down from a peak of £474 million in 2008.

Last year the club raised around £500 million of funds via a bond issue, so that they could repay the previous bank loans, in order to fix the club’s annual interest payments for a longer period (up to 2017), thus ensuring more financial stability. However, there was a price to be paid, which can be seen with a comparison to Arsenal’s bonds, as the debt has to be repaid quicker (7 years vs. 21 years) and the interest rate is higher (8.5% vs. 5.75%).

The really annoying thing for United fans is that this is still unproductive debt. While clubs like Chelsea and Manchester City have used their debt to fund the purchase of better players and Arsenal used theirs to build a new stadium, United’s debt was only used to enable the Glazers to buy the company.

At least the owners managed to find £249 million last November to pay off the prohibitively expensive Payment In Kind notes (PIKs), which carried a stratospheric interest rate of 14.25% (rising to 16.25%), though it is unclear how they funded this repayment. Including the PIKs, United’s gross debt was at one point as high as £773 million with annual interest payments of around £70 million. To paraphrase Winston Churchill, “never has so much been owed by so many to so few.”

"Emirates Stadium - good debt"

Included within the net debt as at 30 June 2011 are astounding cash balances of £151 million, though this was boosted by cashing the £80 million Ronaldo cheque and the £36 million upfront payment from the shirt sponsor. United’s board has argued that it likes to retain so much cash to provide “flexibility”, but this seems a strange decision when they have to pay 8.5% interest on the bonds, while cash balances are unlikely to attract more than 2% interest.

The latest financial engineering from the Glazers is the decision to float a minority stake of the club via an IPO (Initial Public Offering) on the Singapore Stock Exchange with whispers suggesting that the board is seeking to raise £600 million for a 30% stake. The IPO was postponed last year due to volatile market conditions, but is now reportedly back on the agenda.

If some of the proceeds were used to repay part of United’s debt, as the club has apparently briefed journalists, then they would benefit from lower interest payments, though this would not improve cash flow if they were then replaced by dividends to the new shareholders.

Arsenal have now eliminated the debt they built up as part of the property development in Highbury Square, reducing gross debt to £258 million as at end-May 2011. That comprises the long-term bonds that represent the “mortgage” on the Emirates Stadium (£231 million) and the debentures held by supporters (£27 million). Once cash balances of £160 million are deducted, net debt was down to only £98 million, which is a significant reduction from the £136 million last year and the £318 million peak in 2008.

Many fans ask whether it would be possible for Arsenal to pay off the outstanding debt early in order to reduce the interest charges, but chief executive Ivan Gazidis has implied that this is unlikely, arguing that not all debt is bad, “The debt that we’re left with is what I would call ‘healthy debt’ – it’s long term, low rates and very affordable for the club.” In any case, the 2010 accounts clearly stated, “Further significant falls in debt are unlikely in the foreseeable future. The stadium finance bonds have a fixed repayment profile over the next 21 years and we currently expect to make repayments of debt in accordance with that profile.”

So, Real Madrid and Barcelona might not exactly be sitting pretty in terms of debt, but their situation is not quite as bad has been made out. However, it is true to say that debt is a major issue for many other Spanish clubs.

A recent study by Professor José Maria Gay de Liébana of the University of Barcelona revealed that total debt of La Liga clubs was €3.5 billion with half of them having negative equity (though it should be noted that the accounts from seven clubs were only from the 2009/10 season and two from as far back as 2008/09).

As Professor Gay said, “Everyone is concentrated on Madrid and Barca, who are the kings of the banquet, while the rest live a real uncertain future. Many clubs are living dangerously.”

While Madrid and Barcelona unsurprisingly top the list with debt (total liabilities) of €590 million and €578 million, seven other clubs have debt over €100 million, most notably Atletico Madrid €514 million, Valencia €382 million (even after selling stars like David Villa, David Silva and Juan Mata) and Villarreal €267 million. In contrast to the big two’s debt cover (by revenue) of around 80%, theirs is much lower, e.g. Atletico Madrid just 19%.

Spanish football’s struggles are highlighted by the fact that no fewer than six clubs in the top division are currently in bankruptcy protection: Racing Santander, Real Mallorca, Real Zaragoza and all three promoted clubs (Real Betis, Rayo Vallecano and Granada). Furthermore, the beginning of this season was delayed by a players’ strike over unpaid wages. The figures are frightening with 200 players owed a total of €50 million, up from €12 million owed to 100 players the previous year.

"Athletic Bilbao: good football, low debt - what's not to like?"

This is due to two factors: (a) Spanish football’s inability to govern itself properly; (b) the awful state of the economy.

Up until recently, the Spanish Football League (LFP was unable to impose any meaningful sanctions on financial miscreants, but a new law came into force in January 2012 that now authorises the authorities to relegate a club in administration – though whether they have the stomach for a confrontation with a club’s supporters is debatable.

In fairness to the LFP, they have also been impacted by the troubled economy, as Spain is entering recession with a record unemployment rate of 24% (a horrific 40% for young people) and Standard & Poor’s cutting the country’s credit rating. As LFP president José Luis Astiazaran noted, “We are not immune to the wider economy.” Professor Gay agreed, “Football is largely a reflection of what has been happening in our economy, with people spending way beyond their income, relying on fanciful growth forecasts and ending up with unsustainable debt and an asset pricing bubble.”

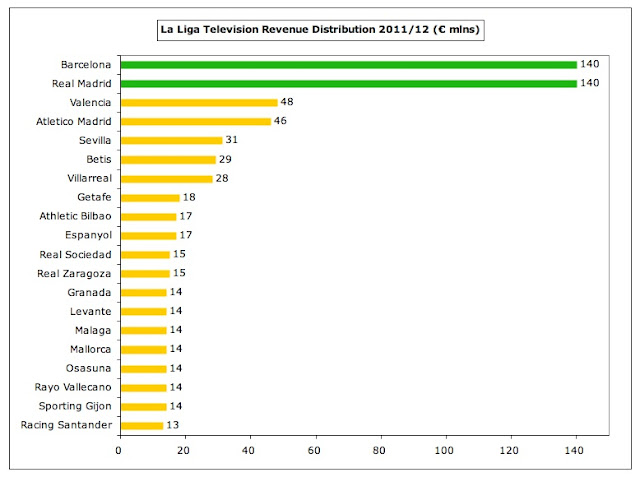

It could be argued that the dominant position of the two Spanish powerhouses is slowly killing Spanish football. This financial pre-eminence is boosted by the “every man for himself” approach taken with the individually negotiated TV deals. Madrid and Barcelona both trouser €140 million a season with the nearest club to them, Valencia, receiving about a third at €48 million. Thirteen of La Liga’s clubs receive between €13-18 million, including Athletic Bilbao with just €17 million. What price them holding on to all of the scintillating young talents that have enthralled us during their Europa League campaign?

Spain is unique among the leading European leagues in not having a collective TV deal, which explains why accusations of selfishness have been aimed at Madrid and Barcelona. The Sevilla president, José Maria del Nido, complained, “We cannot allow a situation where, because two clubs are very powerful, they bring about the demise of the Spanish league.”

That said, football is an amazingly resilient industry and it has not yet collapsed under the weight of debt in Spain, even though the issue is not a new one. In fact, La Liga debt has been about the same level of €3.5 billion for the last four years. Although it rose €50 million last season, the 2001 debt of €3.53 billion is actually lower than the €3.561 billion peak in 2008.

Nevertheless, there is no room for complacency, when a comparison is made with the other major European leagues. At €3.5 billion, Spanish liabilities are by far the highest, almost a billion Euros more than Serie A €2.7 billion (up €327 million in 2010/11) and the Premier League €2.6 billion (2009/10 figure). The debt levels in the financially disciplined leagues are unexpectedly much smaller: the Bundesliga €0.9 billion and Ligue 1 €0.7 billion.

In addition, the Spanish league also has the worst debt coverage (in terms of revenue) at 47% compared to the others: Serie A 63%, Premier League 95%, Ligue 1 140% and the Bundesliga 193%.

This sad state of affairs was underlined when it emerged that Spanish clubs owed the taxman €752 million, including €426 million from clubs in the top division. In fact, that came from just 14 of the 20 clubs, as the remaining six had no outstanding tax debt. According to the AS newspaper, that included Real Madrid, which seems a little strange, as both the club’s accounts and the study by Professor Gay do list tax liabilities.

Once again, Atletico Madrid have the dubious honour of leading the pack with the largest tax debt of €155 million, even after paying the €50 million from the sale of Sergio Aguero to Manchester City directly to the tax authorities. The next highest was Barcelona with €48 million.

This high level of tax debt is galling to many, particularly given the fragile Spanish economy, not to mention the fact that Spain has five clubs in the semi-finals of the Champions League and the Europa League – including the aforementioned Atletico Madrid.

As always, Uli Hoeness, the forthright president of Bayern Munich, got straight to the point, “This is unthinkable. We pay them hundreds of millions to get them out the shit and then the clubs don’t pay their debts.” In fairness, some clubs have negotiated payment plans with the authorities, such as Atletico Madrid (€15 million a year), Levante (5 years) and Mallorca (10 years).

On top of that, the Spanish government and the football league recently announced new rules that would pave the way for the clubs to repay the outstanding tax debts, as the threat of intervention from European Union anti-trust officials loomed large. The LFP said, “Economic control will be strict, as well as the sanctions regime.” These measures will include clubs being obliged to set aside 35% of TV rights revenue for tax payments from the 2014/15 season; clubs possibly being forced to sell players to raise cash; and clubs maybe even booted out of the league.

"Holidays in the sun"

Of course, Spain is hardly unique in having clubs facing severe tax issues, as fans of Rangers and Portsmouth would no doubt attest, but it is the magnitude of the debt in Spain that is concerning, especially given the relatively low revenue of some of the clubs involved.

Given the understandable focus on tax liabilities recently, it might also be a good idea for UEFA to include these in their definition of debt in order that clubs take this issue more seriously than they appear to have done in the past. It is actually a little strange that UEFA do not, as Article 50 of the FFP regulations specifically states that there should be no overdue payables to social/tax authorities (as well as employees) in the same way that Article 49 prohibits overdue payables towards football clubs. While the latter is included in their definition of net debt, the former is not.

In conclusion, while there are some very real debt problems in Spanish football, the situation is not quite so dramatic at Barcelona and Real Madrid as some would have people believe. It would obviously be better for their balance sheets if the debt was lower, but their ability to generate revenue is unsurpassed, admittedly partly due to the current unfair TV deal, but also their high gate receipts and awesome commercial strength. These operations continue to grow, as seen by Barcelona’s record-breaking shirt sponsorship deal with the Qatar Foundation and Real Madrid’s plans to build a $1 billion holiday resort in the United Arab Emirates.

"Put your shirt on it"

Of course, the two Spanish giants may still come under pressure from their creditors at some stage, especially if they embark on a summer spending spree following the disappointing Champions League semi-final exits. Nor should the impact of Spain’s faltering economy be trivialised, but the fact is that right here, right now, the important debt (bank loans, transfers and tax liabilities) is relatively low, at least for clubs of this size.

When reading reports on how much Barcelona and Real Madrid owe, it’s not quite a case of “don’t believe what you read”, but you do need to understand what any analysis is actually referring to, because, as we have seen, debt has many different definitions.

Caveat emptor – or something like that.

0 comments:

Post a Comment