In August 2011 it looked like a new dawn was breaking at Queens Park Rangers, who had just been promoted to England’s top flight for the first time in 15 years. Moreover the Malaysian entrepreneur Tony Fernandes had bought a majority 66% shareholding in the West London club from the previous shareholders, who included the Formula One supremo Bernie Ecclestone and team principal Flavio Briatore.

Compared to his flamboyant predecessors, the affable founder of Air Asia seemed far more level-headed and was certainly much more communicative with the fans. Furthermore the remaining 33% of the club was owned by the family of Lakshmi Mittal, one of the wealthiest men in Britain, whose son-in-law, Amit Bhatia, is on the board.

However, despite the new chairman’s best intentions, it has pretty much been a case of “out of the frying pan, into the fire” since those heady days. QPR have just been relegated to the Championship for the second time in three seasons after a string of insipid, embarrassing performances. It is true that QPR secured promotion at the first attempt in 2013/14, but even this was slightly fortuitous after Bobby Zamora’s last minute goal deprived a superior Derby County team in the Championship play-off final.

The poor performances have resulted in many managerial changes with Neil Warnock, Mark Hughes and Harry Redknapp leaving after poor starts to their respective Premier League campaigns. All of them were given substantial backing in the transfer market, but pretty much wasted the club’s money on a series of awful players, who largely fitted the same profile: past their prime, bad injury record, seemingly unmotivated and bang average.

"That's Zamora"

Clearly Tony Fernandes inherited numerous problems with the recruitment of over-paid, mediocre players seemingly endemic in the club’s culture, but his original promises of financial prudence and sustainability are now little more than a distant memory. On his arrival he boomed, “Football needs to change. There are clubs who are spending money that if they were in a real business they could not afford.”

Since then the strategy has changed to one of getting to the Premier League at all costs – in order to benefit from the lucrative Premier League TV deals. As Fernandes put it, “A critical driver of any club’s value is its presence in the Premier League. The financial results reflect the club’s focus on trying to achieve on-pitch success.”

He added, “Anyone who says we are gambling, then of course we are, but we are sensible with what we are doing.” Given the hefty losses and significant increase in debt, that is fairly debatable, though it is true that QPR did require major funding after years of under-investment if they were to have a realistic chance of establishing themselves as a Premier League club.

It might be that the strategy itself was not totally flawed, but there’s surely no argument that the execution has been fairly disastrous. So much so that the club has not only massively under-performed on the pitch, but is also being threatened with a substantial fine being imposed by the Football League if they are found guilty of breaking Financial Fair Play (FFP) rules in the most recent Championship promotion season.

Although the 2013/14 reported loss was only £9.8 million, which represented a £55.6 million improvement on the previous year’s £65.4 million loss, this was largely due to the inclusion of a £60 million exceptional item for the write-off of some of the shareholder debt.

Revenue fell £22 million (36%) from £61 million to £39 million following relegation with reductions across the board: broadcasting was down £15 million from £43 million to £28 million, while commercial and gate receipts were also lower in the second tier, by £5 million and £3 million respectively.

This was offset by a £22 million reduction in expenditure, which was described by the club as being “mainly driven by player costs”. This seems strange, as the wage bill was only cut by £3 million to £75 million, while player amortisation fell by just £0.5 million. In fact, the main reason for the reduction was other expenses, which decreased by £19 million (65%). This sizeable movement is not explained, though one reason is likely to be Mark Hughes’ severance payment in 2012/13, which was reported at £4.5 million.

The other main year-on-year movement came from player sales, which were not only £5 million lower, but actually generated a loss of £4 million.

QPR’s reported loss of £10 million was the 9th worst in the Championship in 2013/14, but would have been comfortably the highest without the £60 million debt write-off. Excluding that exceptional item, the underlying loss was a barely credible £70 million.

Of course, the vast majority of clubs in the Championship lose money with only three of the 24 contenders making money in 2013/14 and nine losing more than £10 million. Strikingly, all three profitable clubs (Blackpool, Wigan Athletic and Yeovil Town) have since been relegated to League One. This loss-making approach is partly a result of low TV money in England’s second tier, but also due to many clubs over-spending in order to reach the promised land of the Premier League.

QPR obviously managed to clear this hurdle, but their “real” £70 million loss was by far the biggest in the Championship, much higher than the nearest challengers (Blackburn Rovers £42 million, Nottingham Forest £23 million). As a comparison, Leicester City and Burnley were also promoted, but made much smaller losses, £21 million and £8 million respectively.

This has resulted in an unwelcome double for QPR, as they also made the largest losses in the Premier League in 2012/13 with their £65 million deficit being worse than Aston Villa, Manchester City, Chelsea and Liverpool (all around £50 million). In fact, QPR’s loss that season has only ever been surpassed in English football by Manchester City and Chelsea, which underlines just how large it really was.

On the same theme, QPR’s reported £25 million loss in the previous promotion season in 2010/11 was also the highest in the Championship. In other words, in three of the last four seasons QPR have produced the highest losses in their division. That takes some doing, given how badly run many football clubs are.

In the last six seasons QPR have reported aggregate losses of £156 million, but this rises to £218 million if exceptional debt write-offs of £62 million are taken into consideration. Financially this is a real tale of woe, but it’s the last two years that have really set the cat among the pigeons with the club making total losses of £135 million in that period alone (excluding the fancy footwork in the accounts).

In 2010 the club promised to “look to reduced costs across all areas of the business in order to improve its loss making position”, but the considerable investment in the playing squad has thwarted that objective.

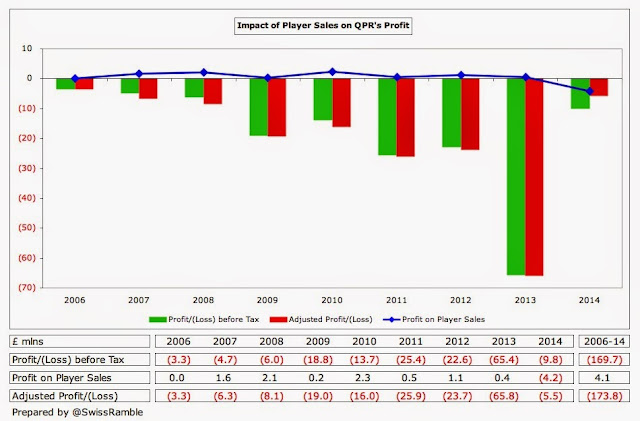

Many clubs that run at an operating loss try to reduce the shortfall through player sales, but QPR have made virtually no money from this activity: just £4 million in the past nine years. Year after the year the accounts include a lengthy list of players that have been released for no money, either retiring, leaving by mutual consent or departing when their contracts expired.

This is a pretty good sign that the club has made some terrible purchases. As an example, the following players left in this way in 2014: Ji-Sung Park, Esteban Granero, Julio Cesar, Andrew Johnson, Aaron Hughes, Jermaine Jenas, Gary O’Neil, Stephan Mbia and Luke Young.

In fact, QPR actually made a loss on player sales (i.e. sales receipts less than the players’ value in the books) of £4.2 million in 2013/14. In fairness, few clubs in the Championship make decent money from player sales with the highest last season being Wigan Athletic £13 million and Bournemouth £7 million. However, only three contrived to actually lose money, the others being Blackburn Rovers and Leeds United.

It might be different this summer, as quite a few players could leave following relegation. In particular, Charlie Austin would probably generate at least £10 million, while reasonable money could also be asked for the likes of Leroy Fer, Steve Caulker and Matt Phillips. QPR might also benefit if Liverpool sell Raheem Sterling, as they are apparently due 20% of any transfer fee under the terms agreed when the Reds signed him from Rangers’ academy in 2010. If his fee were as high as £50 million, QPR would receive a cool £10 million.

While QPR’s revenue grew £7 million in the Ecclestone/Briatore era, mainly thanks to new commercial deals, the real growth came after promotion in 2011/12, when revenue surged nearly 300% from £16 million to £64 million. In the same way, relegation back to the Championship in 2013/14 reduced revenue by 36% to £39 million, though the pain was mitigated by parachute payments of £24 million.

As the club put it, “The impact of relegation and promotion inevitably has a material impact on the short-term financial results of clubs.” This is largely due to the disparity between the different TV deals in England’s top two leagues. In fact, £27 million of QPR’s £29 million revenue growth between 2006 and 2014 came from television, where the club admitted that they did “not have any influence on the outcome of the relevant contract negotiations.”

Of course, the 2014/15 accounts will reflect the year back in the Premier League with revenue at a record level of around £75-80 million, reflecting the higher TV money from the three-year deal that commenced in 2013/14 and growth in gate receipts and commercial income.

However, relegation from the Premier League will then once again adversely affect the 2015/16 numbers. As head coach Chris Ramsey observed, “The implications of going out of the division are huge.” Even with a parachute payment of £25 million, revenue will probably drop by around £40 million.

Despite the decrease in 2013/14, QPR still had the highest revenue in the Championship with their £39 million just ahead of Reading £38 million and Wigan Athletic £37 million. Money often talks in football, so it is no surprise that two of the four clubs with the highest revenue were promoted that season, namely QPR and Leicester City, though Burnley also achieved the same feat with the 11th largest revenue of £20 million.

The three clubs with the highest revenue all benefited from £24 million of parachute payments after relegation from the Premier League. If these were to be excluded, a slightly different picture emerges with Leicester City on top of the pile with £31 million, followed by Leeds United £25 million, Brighton £24 million and Derby County £20 million, though QPR would have still been in a very respectable 5th place with £17 million (£39 million less £24 million parachute payment plus £2 million solidarity payment).

In the Premier League broadcasting had accounted for 70% of QPR’s total revenue, but this actually increased to 72% in the Championship, partly due to the parachute payments, but also because the other revenue streams fell considerably in the second tier.

In 2013/14 QPR’s broadcasting revenue fell £14.7 million (34%) from £42.7 million to £28.1 million, including £24.1 million of parachute payments, though this was still the second highest in the Championship. Normally in that division clubs receive the same annual sum for TV, regardless of where they finish in the league, amounting to just £4 million of central distributions: £1.7 million from the Football League pool and a £2.3 million solidarity payment from the Premier League.

It should be noted that those clubs receiving parachute payments like QPR do not also receive solidarity payments. Other money is dependent on whether a team reaches the play-offs, cup runs and the number of times a club is broadcast live.

Looking at the Premier League television distributions, the massive financial inequality between England’s top two leagues becomes evident with Premier League clubs receiving between £62 million and £98 million in 2013/14, compared to the paltry £4 million in the Championship.

The value of the new Premier League television deal in 2013/14 can be seen by QPR “only” earning £40 million for finishing 20th (last) in 2012/13, which was £22 million less than the £62 million Cardiff City received when they claimed this dubious honour the following season.

QPR will have received a similar sum in 2014/15, but are now back to a life of parachute payments. These are currently worth £65 million over four seasons: £25 million in year 1; £20 million in year 2; and £10 million in each of years 3 and 4.

These will very likely increase in 2016/17 when the recent blockbuster Premier League TV deal comes into play, but so will the distributions in the top flight. My estimate is that the bottom club’s share will rise by £30 million to £92 million, while the year 1 parachute will only increase by £11 million to £36 million. This means that the gap to the Premier League would further increase: from £35 million (£62 million minus £27 million) to an amazing £54 million (£92 million minus £38 million).

This huge difference in revenue doesn’t quite excuse QPR’s profligacy, but it does explain it to a certain extent.

QPR’s match day revenue fell by £2.7 million (32%) from £8.3 million to £5.6 million in 2013/14 as ticket pricing was reduced “to reflect that we were playing in the Championship”. This was the 8th highest in that division, but this is not a great money spinner for any of the clubs playing at this level, e.g. only three earned more than £7 million: Brighton £10.4 million, Leeds United £8.6 million and Nottingham Forest £7.2 million.

Revenue was also impacted by QPR’s attendance dropping by around 1,100 from 17,779 to 16,656 (including more than 10,000 season ticket holders), which was the 9th highest in the Championship, way behind Brighton 27, 283 and Leeds United, Derby County and Leicester City (all around 25,000).

As might be expected, QPR’s attendances are higher when they compete in the Premier League, so have increased to 17,809 in 2014/15, but this is still the smallest in the top flight. To place this into context, it’s around 1,300 lower than Burnley, their fellow relegated team, despite the club’s claim that they are “confident that our pricing structure will help to encourage fans to attend.”

Part of the problem is the very low 18,489 capacity at Loftus Road, which is far from ideal for a club with aspirations of competing at the top level. It is therefore no surprise that the club has been looking to move to a new 40,000 seat stadium with the Old Oak Common site in north-west London being identified.

However, there is strong opposition from the site owner, Car Giant, coincidentally a former QPR sponsor, who stated that they had no plans for a football stadium in their development, so this would appear to be a non-starter. There is also the small matter of how the club would finance a new stadium. Interestingly, the accounts include £4 million spent on Rangers Developments Limited in the note on Related Party Transactions, though this is not explained.

QPR’s commercial income slumped badly following relegation, almost halving from £9.6 million to £5.0 million. This is maybe not that big a surprise, given that the club had previously stated that it “believes that its Premier League status will help it to significantly increase its commercial revenue.”

In fairness, £5 million is not too shabby in the Championship and is actually the 7th highest. It may be a long way behind Leicester City £19 million (boosted by a major marketing deal with Trestellar Limited) and Leeds United £12 million, but no other clubs manages to earn more than £8 million. Only the elite English clubs can earn vast sums commercially, but it must be galling to QPR that their near neighbours Fulham have managed to earn more than twice as much as them with £12 million.

QPR are currently in the third year of a shirt sponsorship deal with AirAsia, extended for the 2014/15 season, which was reportedly worth £2.5 million in the Premier League. If that figure is correct, then it compares favourably with clubs like West Ham and Stoke City, though it is obviously miles behind the deals for Manchester United, Arsenal, Liverpool, Manchester City and Chelsea. Nike are QPR’s kit supplier in a five-year deal running to May 2019.

What has really destroyed QPR’s finances is their unbelievable wage bill. Whichever way you look at this, it is fairly appalling. After promotion in 2012 it nearly doubled from £30 million to £58 million and then rose again the following season to £78 million. In the last four seasons the headcount has exploded from 104 to 169, including a 43 increase in the number of players, managers and coaches from 69 to 112.

Despite relegation the wage bill was only trimmed by £2.6 million (3%) from £78 million to £75.4 million, increasing the wages to turnover ratio from 129% to an almost unimaginable 195%. In other words, QPR spent twice as much on wages as their income – and then had to fund all their other expenditure.

Almost every club in the Championship has a dreadful wages to turnover ratio with 10 of them being more than 100%, but QPR’s is in a class of its own with the only clubs approaching a similar ratio being Bournemouth 172%, Nottingham Forest 165% and Millwall 132%.

In fact, QPR’s wage bill of £75 million was not only the highest in the Championship, but more than twice as much as the closest challengers, Leicester City, who managed to win the league on a wage bill of £32 million. The other promoted club, Burnley, somehow got by with wages of £15 million.

QPR stated that they operate “in a highly competitive market for talent and the market rates for transfers and wages is, to a varying degree, dictated by competitors.” There’s some truth in that, but let0s be honest: QPR’s wage bill is out of all proportion to their market (and indeed their performances on the pitch). Admittedly, the 2013/14 wages would have included promotion bonuses, but these are unlikely to be more than £5 million (based on the £4.6 million Crystal Palace paid the previous season).

To further emphasise the ridiculous nature of QPR’s wage bill, only seven clubs in the Premier League paid more than them in 2013/14. The good news is that the club appears to have learnt its lesson from the last time they went down, so most players’ contracts now include relegation clauses.

Another cost that has hurt QPR’s numbers is player amortisation, which has risen from £3 million in 2011 to £17 million in 2014, reflecting higher expenditure on player purchases. This represents the annual cost of expensing player purchases, as transfer fees are not fully expensed in the year a player is purchased. Instead, the cost is written-off evenly over the length of the player’s contract – even if the entire fee is paid upfront. As an example, Charlie Austin was bought from Burnley for a reported £4 million on a three-year deal, so the annual amortisation in the accounts for him is £1.333 million.

This might not sound much compared to some of the other large numbers in QPR’s accounts, but (stop me if you’ve heard this one before) it was still the highest in the Championship in 2013/14, around £10 million more than Blackburn Rovers £7 million.

There has been significant investment in the transfer market since Tony Fernandes arrived in 2011. In the last four years, QPR had a net spend of £68 million, which compared to just £14 million in the previous nine years. In the last accounts, Fernandes observed, “We have worked to put together a squad of players that we believe have the skill and ability to secure QPR’s place in the Premier League beyond this season.”

Although it has not exactly worked out as well as the club would have hoped, there is no doubt that the board has provided substantial financial backing to its various managers – though that was maybe not the best idea, especially when one of those is a certain Harry Redknapp, whose track record in helping to balance a club’s books leave a lot to be desired.

In fact, QPR have been one of the biggest spenders in the Premier League with only six clubs outspending them over the last four years, basically the usual suspects (Manchester United, Manchester City, Chelsea, Liverpool and Arsenal) plus West Ham.

The hope is that QPR will now do it differently with Fernandes claiming, “Our recruitment policy is changing. This is a new strategy for us. We want to develop a philosophy of buying young, hungry players who can go on to forge decent careers with us.”

All of this spending has been built on a mountain of debt, which has risen from £14 million in 2006 to £185 million in 2014, which is pretty shocking given that the club has spent two years in the Premier League since then. It’s not as if QPR has built a winning team or invested the money on improving infrastructure like a new stadium.

Incredibly, the figure would have been even higher at £250 million if the shareholders had not written-off £60 million and converted £5 million into equity (the maximum permitted by FFP rules) in 2014. Just pause for a moment and consider that: a quarter of a billion debt.

Most of the debt (£158 million) is owed to the club’s owners and is non-interest bearing, comprising £115 million to Tune QPR Sdn Bhd (a company controlled by Fernandes), £33 million to Sea Dream Limited (a company owned by the Mittal family) and £10 million to Amulaya Property Limited (a company entirely owned by Tune QPR and Sea Dream). However, in the last two years, the club has also taken on £27 million of bank loans, secured on the Loftus Road Stadium, which may be a cause for concern.

Another interesting point is that Sea Dream Limited only waived £6.6 million of the £60 million debt write-off, leaving the vast majority (£53.4 million) to Tune QPR Sdn Bhd, which is nowhere near the ownership proportions of Sea Dream 30% and Tune QPR 69%. It’s pure conjecture, but it would appear that Mittal was not overly keen to pay for Fernandes’ errors.

In the Championship only one club, Bolton Wanderers, had a higher debt than QPR at £195 million, with the next highest being Brighton £131 million and Ipswich Town £86 million. To further underline the magnitude of QPR’s debt, only two Premier League clubs had a higher balance: Manchester United £342 million (following the Glazers’ leveraged buy-out) and Arsenal £240 million (after building the Emirates Stadium).

In the last four years QPR had a cash outflow of £134 million from operating activities, but still spent £67 million (net) on player purchases. This was funded by an additional £191 million of shareholder loans, including £57 million in 2014 and £73 million in 2013, plus £27 million of new bank loans. The question is how much longer will the shareholders be prepared to put in such large sums with so little return (both on and off the pitch)?

It is also worth noting the feeble investment in long-term infrastructure with less than £7 million being spent on capital expenditure in the same period, despite all the fine talk of a new stadium and a new training complex at Warren Farm in Hanwell.

To add insult to injury, QPR are now facing the threat of a hefty Financial Fair Play fine from the Football League, who have queried the “treatment of certain items in their accounts”, namely the £60 million debt write-off. The FFP regulations would appear to rule out treating such a transaction as income, though QPR might argue that this particular write-off can be booked in this way, as the debt was not converted into equity (as is often the case).

Under the existing rules, clubs are only allowed a maximum annual loss of £8 million (assuming that any losses in excess of £3 million are covered by injecting equity). Any clubs that exceed those losses are subject to a fine (if promoted) or a transfer embargo (if they remain in the Championship). There is a sliding scale for the next £10 million of losses amounting to a £6.7 million fine, but beyond £18 million the fine is imposed on a pound-for-pound basis.

"Everything's Gone Green"

If the £60 million debt write-off is not allowed, that would imply an enormous fine of £58 million, though it has been suggested that deducting allowable expenditure like youth development and promotion bonuses would reduce that to £43 million. Either way it’s a huge amount of money that would set back QPR’s plans to bounce back to the Premier League at the first attempt. If they refused to pay, they could theoretically even be banished to the Conference.

However, QPR have challenged the legality of these rules. Their defence might include a number of factors, especially the fact that the Football League has already modified the rules that were applicable in 2013/14, while UEFA have also recently relaxed their version of FFP. Furthermore, it’s not as if QPR have tried to be particularly subtle about their accounting, unlike other clubs who have employed more “legitimate” means such as booking large impairment charges before relegation.

As always, Fernandes is expecting a favourable outcome: “I’ve always been very confident that a positive resolution will come out of the FFP case that is fair to everyone.” Even though those Championship clubs that have strived to stay within the rules might be unhappy, it would not be that big a shock if some form of compromise settlement on a lower sum would be agreed.

In many ways, QPR are fortunate to have Fernandes, who cannot be accused of under-funding the “project”, but to date he has given the impression of being one of those successful businessmen that seem to forget the strategies that have worked so well in their day job once they enter the world of football.

"Was it something that I said?"

Damned if you do, damned if you don’t, it could be argued, but it must be possible to spend so much money better than this. QPR’s owners are among the wealthiest in the world, but it may just be that the football club is way down their list of priorities. Despite the best of intentions, it is arguable that the club have not really made any progress since Fernandes turned up in 2011.

They are once again back in the Championship, though the chairman argued, “This time we go down in a much stronger position, with a better structure in place and better solutions to pursue what we want to do in the long term.” Certainly, there is the opportunity to rebuild with nine senior players out of contract at the end of the season and four loanees returning to their parent clubs, while a new, experienced chief executive, Lee Hoos, has been recruited from Burnley.

Of all people, Chris Ramsey the new head coach spoke sensibly about what needs to be done: “Everybody would want to bounce straight back into the Premier League and I am sure that’s what we’re going to try and do, but we have to be realistic. It’s important that everybody around the club realises that we have to get some stability and foundations in place to make sure that the future looks bright for Queens Park Rangers.”

That might not be particularly exciting, but some stability and a healthy dose of realism might be exactly what QPR need.