Having tried so hard to reach the Premier League, it must have been a bitter pill to swallow for Cardiff City, as the Bluebirds only managed to stay in the top flight for one brief season before dropping back to the Championship. They had been knocking on the door for so long, being eliminated in the play-offs for three consecutive seasons, before finally securing automatic promotion after comfortably winning the division in 2013.

The club had been guided to success in that memorable season by Malky Mackay, but a disappointing start to Cardiff’s first ever Premier League campaign, allied with a breakdown in trust over transfers between the manager and owner, Vincent Tan, resulted in the Scot’s departure in December. He was replaced by the former Manchester United star, Ole Gunnar Solskjaer, who could not prevent relegation. His torrid time in charge ended in September 2014, when Russell Slade took his place.

The former Leyton Orient manager is renowned for operating within a tight budget, which is a quality that will be all too necessary for Cardiff, whose recent history features numerous financial problems. That said, supporters will have been disappointed with the performances of Slade’s team on the pitch so far, as Cardiff ended the 2014/15 season in an inadequate 11th place in the Championship, the worst finish since the 2008.

"Bruno, Bruno"

Big spending under the previous owners, including the controversial figures of Sam Hammam and Peter Ridsdale, who had plenty of previous at other clubs, had brought Cardiff to the brink of administration, as they endured a winding-up order over unpaid taxes and a transfer embargo imposed by the Football League.

New investment in May 2010 from a group of Malaysian businessmen, including that man Tan, stabilised the club’s finances. Not only that, but Tan proceeded to spend heavily to finance the club’s promotion attempts and gave strong backing to both Mackay and Solskjaer in the transfer market.

However, this came at a price with Cardiff reporting a string of heavy losses and building up substantial debt. Despite record revenue of £83 million in the Premier League, Cardiff still somehow contrived to make a £12 million loss, which was surely not part of the grand plan.

In fairness, Cardiff’s loss had improved by £18 million from a staggering £30 million in the Championship, but it still meant that the club lost £1 million every month and the accounts were just as much in the red as the shirts worn in the top flight.

Revenue shot up by £66 million from £17 million to £83 million, largely on the back of the Premier League television deal, but Cardiff also reported increases in all cost categories, even though the previous year had included £5.2 million of once-off payments triggered by promotion.

The wage bill rose £20 million (62%) from £33 million to £53 million, while player amortisation nearly doubled from £7.4 million to £14.5 million as a result of “significant enhancements to the first team squad.”

There were also a number of not inconsiderable once-off items, some of which were linked to poor work in the transfer market: (a) impairment of player values increased by £3 million from £4 million to £7 million; (b) there was a loss on player disposals of £5 million, including the sale of hapless Danish striker Andreas Cornelius back to FC Copenhagen for a fraction of his purchase price.

There was also a £5.5 million write-down of the value of the new East Stand, as this was not to be used in the first season back in the Championship. Exceptional items of £2 million covered termination payments following Mackay’s departure, though these were at a similar level to 2013 exceptionals, which were mainly due to the discount on loan note liabilities.

The club benefited from another interest credit of £1.6 million, but this was lower than the previous year’s £5.3 million accrual release, which represented interest waived on Tan’s loans.

All of this meant that Cardiff were one of just five clubs in the Premier League to make a loss in the 2013/14 season with only Fulham (£33 million), Manchester City (£23 million) and Sunderland (£17 million) registering larger deficits. Most clubs managed to move into the black following the increase in TV money that season.

Promoted clubs normally have to splash out in their first season in the Premier League in order to build a squad that can hope to compete at the higher level, but Cardiff were the only one of the three to fail to make a profit. Hull City moved from a £26 million loss in the Championship to a £9 million profit in the Premier League, while Crystal Palace’s profits increased from £2 million to £23 million. In particular, it is striking how much higher Cardiff’s expenses were than the other two clubs.

Clearly Cardiff’s financial results were greatly influenced by the £12 million of impairment charges they booked (players £6.6 million, stadium £5.5 million). To better understand the reasons for the player impairment, we need to explore how football clubs account for player purchases. Importantly, transfer fees are not fully expensed in the year a player is purchased. Instead, the cost is written-off evenly over the length of the player’s contract via player amortisation – even if the entire fee is paid upfront.

As an example, if a player was bought from for £10 million on a four-year deal, the annual amortisation in the accounts for him would be £2.5 million. After two years, the cumulative amortisation would be £5 million, leaving a value of £5 million in the accounts. However, if the directors were to assess the player’s achievable sales value as £3 million, then they would book an impairment charge of £2 million. Impairment could thus be considered as accelerated player amortisation.

From Cardiff’s perspective, the 2013/14 impairment charge has definite advantages in terms of Financial Fair Play (FFP). As clubs are permitted to make far higher losses under the Premier League regulations (£105 million over three years) compared to the Championship (currently £8 million a year), it makes perfect sense to book impairment charges in the Premier League accounts. This approach has the added benefit of reducing annual amortisation charges in future years (from £2.5 million to £1.5 million in our example).

Cardiff are by no means the only club to employ this fancy footwork in their accounts, though their £12 million impairment charge was only surpassed in 2013/14 by Chelsea £19 million and Fulham (also relegated) £17 million.

Without these impairment charges, Cardiff would have broke even, which would have obviously been a much better result, though it would still have been the fourth worst financial performance in the Premier League.

Of course, losses are nothing new for Cardiff, as they have consistently lost money over the years. This is not entirely unexpected in what the club described as “the challenging financial environment presented by the Championship”, as very few clubs in this league are profitable.

Interestingly, although Cardiff’s current ownership made reference to the “imprudent and careless management” of the previous hierarchy, losses have grown since their arrival: £67 million in the past four seasons compared to “only” £17 million in the preceding four seasons. The difference, of course, is that the new owners have at least been able to fund these shortfalls.

The smallest loss in this period was £0.9 million in 2010, but even this was due to special factors, mainly the profit from the disposal of fixed assets of £7.2 million. This largely referred to the sale of the Ninian Park stadium, which produced proceeds of £7.4 million, plus the sale of plots or land adjacent to the new stadium to companies associated with Cardiff City directors: the hotel site to (former director) Paul Guy for £1.8 million and the House of Sport site to Steve Borley for £450,000.

The 2010 figures also included a £4.2 million profit from player sales, mainly arising from Roger Johnson’s transfer to Birmingham City. That was the last time Cardiff made reasonable money from selling players. In fact, in the four years up to 2010 the club made £17 million profits from this activity, but slumped to a loss of £5 million in the next four years.

Cardiff’s £5 million loss on player sales was the worst performance in this area of any Premier League club in 2013/14. This was in stark contrast to the £104 million profit made by Tottenham, which was ironically due to the sale of Cardiff-born Gareth Bale to Real Madrid.

Cardiff’s chief executive Ken Choo said that they “took the hard decision to incur these losses for the good of the club”, referring to the cost of extricating themselves from the Cornelius purchase (among others). In total the club said that this one transaction cost the club just under £10 million in transfer fees, salaries and agents’ fees.

On the bright side, the 2014/15 accounts should include a positive contribution from player sales after the departures of Gary Medel to Inter and Steven Caulker and Jordan Mutch to Queens Park Rangers.

However, there will also be additional costs incurred with severance payments to Ole Gunnar Solskjaer and his team. This is becoming a recurring theme at Cardiff: as well as the £2.1 million paid out in 2014 to Mackay and his staff, the club also had to pay £1.7 million in 2012 as a result of Dave Jones’ departure.

So Cardiff’s player trading has been disappointing, while the accounts have been impacted by a series of exceptional items, but the underlying business has not been that great either. A good way of checking this is to look at the club’s EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxation, Depreciation and Amortisation), which has been consistently negative, before rising to £22 million in the Premier League season.

In particular, the 2013 EBITDA of minus £20 million was markedly worse than other years. While much of this was attributed to “significant bonus payments in relation to promotion to the Premier League”, this does not fully explain the deterioration. There is a mysterious non-cash movement of £13.8 million mentioned in the cash flow statement, but this is not detailed.

Although Cardiff’s EBITDA improved by £42 million in 2014, their £22 million was still among the lowest in the Premier League, only ahead of Aston Villa £19 million, Sunderland £13 million, WBA £9 million and Fulham £2 million. In fairness, few people would expect them to compete with the likes of Manchester United £130 million and Manchester City £75 million, and Cardiff is around the same as their Welsh rivals Swansea City, who are often portrayed as a model club.

Cardiff’s revenue growth is obviously dominated by the impact of promotion to the Premier League with revenue of £83 million almost four times higher than the £17 million earned in the Championship. Most of the £66 million increase was down to the much higher TV money, which rose £59 million from £5 million to £64 million, but there was also solid growth in commercial income, up £4.7 million from £6.2 million to £10.9 million, and match day, £2.1 million higher at £8.3 million.

Revenue in the Championship years was largely influenced by success on the pitch, either through domestic cup runs or progress to the play-offs. In this way, the increase in 2012 from £15.9 million to £20.2 million was driven by reaching the Carling Cup final against Liverpool, which was worth £2.3 million, while the 2008 growth was similarly enhanced by reaching the FA Cup final against Portsmouth.

Despite the steep revenue growth in 2013/14, Cardiff’s £83 million was actually the lowest in the Premier League in 2013/14, just behind Hull City £84 million and WBA £87 million. It is worth noting that the three relegated clubs (Cardiff, Fulham and Norwich City) were all in the bottom six in revenue terms, though this is admittedly a somewhat of a “chicken and egg” point, as the Premier League TV distributions partly depend on where a team finishes in the league.

Like every other Premier League club, Cardiff were in the top 40 revenue earners worldwide, according to the Deloitte Money League, which sounds very impressive, if it were not for the fact that this does not help at all domestically. For example, five English clubs earn more than £250 million a season with Manchester United leading the way at £433 million – or more than five times as much as Cardiff. This really highlights the magnitude of the challenge for the smaller clubs in the Premier League.

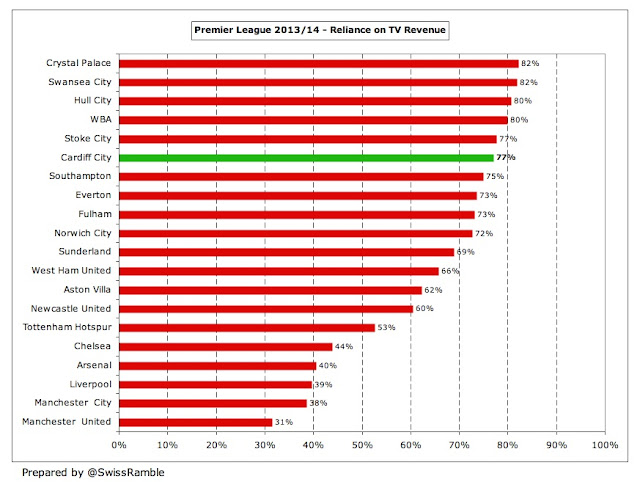

Over three-quarters (77%) of Cardiff’s revenue in the Premier League came from television with just 13% from commercial income and 10% from gate receipts. This was very different to the more balanced revenue mix in the Championship: commercial 36%, match day 36% and broadcasting 28%.

The club notes in the accounts that its principal risk is “substantially lower” broadcasting revenue in the lower leagues, but amazingly five Premier League clubs had an even higher reliance on TV money than Cardiff with Crystal Palace and Swansea City both earning around 82% of their revenue from broadcasting.

Cardiff’s share of the Premier League television money was £62 million in 2013/14, based on the fairly equitable distribution methodology. Most of the money is allocated equally, which means each club receives 50% of the domestic rights (£21.6 million in 2013/14), 100% of the overseas rights (£26.3 million) and 100% of the commercial revenue (£4.3 million). However, merit payments (25% of domestic rights) are worth £1.2 million per place in the league and facility fees (25% of domestic rights) depend on how many times each club is broadcast live.

As a result, Cardiff’s merit payment for finishing last was only worth £1.2 million, compared to the £11.1 million received by 12th placed Swansea City. The Bluebirds’ distributions were also restricted by being broadcast live just 8 times, though they were actually paid on the basis of 10 times, which is the contractual minimum. This meant that they only got £8.6 million, compared to, say, Aston Villa’s £13.1 million for being shown live 16 times.

Of course, in 2014/15 in the Championship Cardiff will receive a lot less TV money, amounting to around £28 million. This will comprise a parachute payment of £25 million and a Football League distribution of £1.7 million plus some money for cup runs, live matches, etc. That will mean a painful reduction in TV money of £36 million year-on-year.

That might sound horrific, but most clubs in the second tier receive just £4 million from television, regardless of where they finish in the league, comprising the £1.7 million from the Football League pool and a £2.3 million solidarity payment from the Premier League. Note: clubs receiving parachute payments do not also receive solidarity payments.

Parachute payments are currently worth £65 million over four seasons (£25 million in year 1; £20 million in year 2; and £10 million in each of years 3 and 4) and have a big influence on a club’s finances in the Championship.

However, the Premier League has recently announced changes to this structure, whereby from 2016/17 clubs will only receive parachute payments for three seasons after relegation, although the amounts will be higher (my estimate is £75 million, based on the advised percentages of the equal share paid to Premier League clubs: year 1 - 55%, year 2 - 45% and year 3 - 20%).

Clearly, being in the Championship will have a major adverse impact on Cardiff’s revenue. On top of the estimated £36 million fall in broadcasting, there will also be reductions in match day and commercial. I would expect gate receipts to fall back by £2 million to around 2012/13 levels of £6 million, as lower average attendances are slightly offset by more home games in the cup competitions; while commercial income is likely to drop by at least a third (£4 million) from £11 million to £7 million, depending on whether sponsorship deals have relegation clauses.

That would produce a total reduction in revenue of £42 million from £83 million to £41 million, though this is still likely to have been one of the highest in the Championship last season (along with fellow relegated clubs, Norwich City and Fulham), which makes Cardiff’s mediocre performance in the second tier all the more disappointing. To place this into context, in the Championship in 2013/14 QPR boasted the highest revenue with £39 million, followed by Reading £38 million and Wigan Athletic £37 million.

Match day income rose by 33% (£2.1 million) from £6.2 million to £8.3 million in 2013/14, but this was still the third lowest in the Premier League, only ahead of Stoke City £7.7 million and WBA £7.0 million. Cardiff’s revenue was actually around £1 million less than Swansea’s £9.2 million, even though their average attendance of 27,430 was considerably better than their Welsh competitors’ 20,407.

In fact Cardiff’s attendance was a very respectable 13th highest in their season in the top flight, though gate receipts were influenced by a five-year freeze on season ticket prices.

Cardiff’s attendances had been on a rising trend since the 13,800 low point in 2007/08, boosted by the move to the Cardiff City Stadium in 2009, with more than 5,000 additional people attending in the Premier League. However, they have lost more than 6,000 (23%) following the return to the Championship and registered their lowest ever crowd of 4,194 at the new stadium for a FA Cup 3rd round match against Colchester United in January.

These are worrying signs, especially as the season ticket sales for the 2015/16 season have only just passed the 10,000 mark, compared to 16,500 last season and 22,500 in the Premier League. This is a sign that many fans have become disenchanted with the club, not least the team’s insipid displays on the pitch.

The club’s net contribution to the new stadium on completion of the core build was £26 million with other funding being provided by the local council, who granted Cardiff a 150-year lease for an annual rent of £180,000. In addition, the club paid the council £720,000 on promotion to the Premier League.

The stadium originally had a capacity of nearly 27,000 when it was completed in 2009, but this has been expanded following a further £12 million investment by the club to 33,280. However, this has effectively been reduced to around 28,000, as the new stand has been mothballed for the forthcoming season due to poor ticket sales.

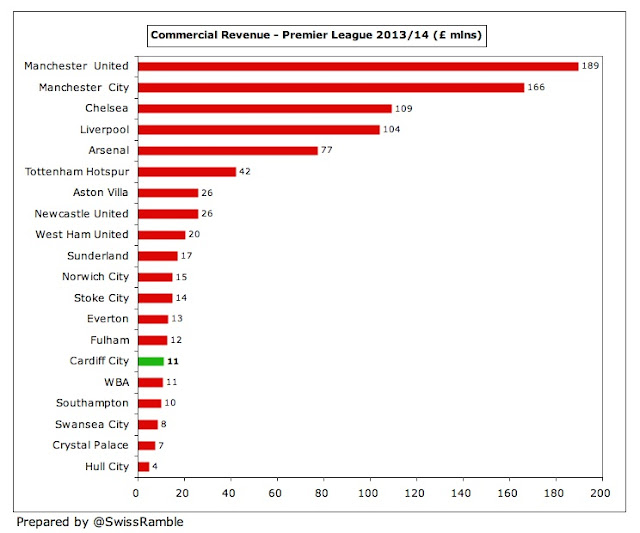

Commercial income surged 75% (£4.7 million) from £6.2 million to £10.9 million in 2013/14. Although this the fifth lowest in the Premier League, that’s a pretty good performance, only just behind Premier League stalwarts Everton £12.7 million and Fulham £12.3 million. As might be expected, clubs like Manchester United £189 million and Manchester City £166 million are out of sight, but that’s not really a valid comparison. A better comparative for Cardiff would be Swansea City, who only generated £8.3 million from commercial operations.

The club has focused on “improved commercial partnerships”, which is fair enough, but few were supportive of the “strategic decision” to change the colour of the home strip from blue to red, even if the “rebranding was seen by the club as a positive step in securing future commercial opportunities.” Fortunately the club decided to revert back to its traditional blue in January 2015, after many supporter protests and diminishing attendances, which may or may not have persuaded Adidas to commit to a long-term kit supplier deal this month.

The shirts are emblazoned with the “Visit Malaysia” slogan, but it is not totally clear how much Cardiff are being paid for the privilege. An analysis by the respected Sporting Intelligence website put the annual value at just £500,000, while the club accounts list various figures: £1 million in 2012, £750,000 in 2013 and nothing in 2014.

A response in the Malaysian parliament suggested that the deal was worth £7.35 million in total, but the Tourism Ministry was only contributing less than half that amount. Again it was not clear whether this referred to an annual figure or the total cost of the deal over a number of years.

The wage bill was up a hefty 62% (£20 million) from £33 million to £53 million, though the underlying increase was probably even higher, as the 2013 figures were inflated by “significant” bonus payments. However, following the massive revenue growth, the wages to turnover ratio improved from a barely credible 189% to a respectable 64%.

Even so, that ratio was still one of the highest in the Premier League, only “beaten” by four clubs. Interestingly, Swansea’s ratio was almost identical to Cardiff.

However, Cardiff’s £53 million was one of the lowest wage bills in the division, only ahead of three clubs: Norwich City £50 million, Crystal Palace £46 million and Hull City £43 million. Money usually talks in the football world, so it is perhaps unsurprising that Cardiff were relegated, though it is worth noting that Palace comfortably outperformed them.

There is one mysterious note in the accounts that mentions an additional £1.7 million paid to “key management personnel” on top of the staff costs. The recipient of this money is not explained, but my guess is that it is linked to a consultancy agreement for someone senior.

In 2014/15 the wages should have been cut considerably in the Championship, as player contracts should include relegation clauses. In addition, Russell Slade has been tasked with slashing the wage bill by offloading a number of players to reduce a squad that had become too bloated. The new austerity was typified by Matt Connolly and Kenwyne Jones being allowed to go on loan to other Championship clubs in the second half of the season for “business reasons”.

It is to be hoped that the club has also managed to cut its Administration Expenses, which have exploded in the last two years, rising from £7 million in 2012 to £16 million in 2013 and then £40 million in 2014. Some of the exceptional items discussed earlier will have had an impact, but that does not fully explain this puzzling increase in non-footballing costs.

For many years Cardiff were essentially a selling club, not least because the Football League imposed a transfer embargo for a while, but Tan has financed a bit of a spending spree (relatively speaking) in the drive to reach the Premier League. Following a series of disappointments in the play-offs, the club recognised that the playing squad had “insufficient strength in depth to sustain a strong promotion challenge”, so this spending was to a certain extent vindicated when they finally achieved their target.

However, this approach did not work so well in the Premier League with Tan furious about what he perceived to be over-spending on players who failed to deliver on the pitch, so much so that Mackay and head of recruitment Iain Moody paid the price with their jobs.

Over the course of the last three seasons, no Championship club has spent more than Cardiff, even after the net sales in 2014/15. In that period, Cardiff’s net spend was £28 million, more than Norwich City £24 million, Fulham £16 million and Nottingham Forest £12 million. Granted, this comparison has to be treated with some caution, as the figures are distorted by clubs that played in the Premier League the previous season, but Cardiff supporters would surely be entitled to expect a better return on this amount of expenditure.

The question is whether Tan will maintain his investment at these levels. The accounts stated, “Following relegation from the Premiership, the owners are aware that they need to again invest to strengthen the playing squad, but that they need to spend wisely.” That’s hardly definitive, nor is it particularly encouraging, given that they made a very similar statement about spending wisely the previous season and that did not work out too well.

Moreover, Russell Slade’s assessment was slightly different, “We are having to shop in a different area. We are not shopping at Harrods now.” Despite the cutbacks, Slade somewhat defiantly claimed that “the ambition is still to try and get into the top six”, but Cardiff’s transformed approach cannot make this any easier.

Cardiff’s total liabilities of £157 million are now £66 million more than the club’s assets and include £135 million of debt. The vast majority of this, £130.3 million, is owed to the club’s overseas shareholders. As £7.5 million has been provided by Torman Finance Inc, a company believed to belong to chairman Mehmet Dalman, the remaining £122.8 million is from Vincent Tan. Interest accrues on these loans at an annual rate of 7%, though the total due to May 2014 was waived in September 2013.

These shareholder loans have been rising at an alarming rate: from £15 million in 2011 to £130 million just three years later. The increase in 2014 alone was £65 million, which just about doubled this debt. To put it simply, Tan basically lent his way to promotion, but is now back to where he started – except he is now significantly out of pocket.

More positively almost all of the other external debt has been paid off with only £4.6 million loan stock remaining. This agreement had been renegotiated down from £24 million to £15 million in 2006 in exchange for future income from stadium naming rights plus a one-off payment of £5 million if the club achieved Premier League status.

"The Iceman Comes"

During 2014 the outstanding debts to PMG Estates Limited (that helped fund the new stadium build) and the Sport Asset Capital player finance fund were finally repaid. In 2009 these had been as high as £9.8 million and £3.8 million respectively. The other stadium loan of £7.1 million was paid off earlier with the proceeds of the Ninian Park sale.

Even though nearly all Cardiff’s debt is owed to the club’s shareholders, it is still a concern, as Tan could demand repayment at any time. It is particularly worrying, given that the owner has frequently promised to convert his loans into equity, which he can do at any time at a fixed conversion price of 15.61 pence per share. Back in August 2013, he stated, “We are in the process of turning loans into equity. It will take the club to almost debt-free, probably in the next couple of months, God willing.”

This may have been derailed by the disagreement with Mackay, but that argument does not really wash. It just seems like he is no longer so keen on the idea following comments made in May 2014: “I will convert some of my debt to equity, but not all, because the amount is very big. Maybe I will convert £50 million and leave £100 million debt.” Actions speak louder than words and he only actually converted £2.5 million in 2014, which hardly seems worth the effort.

As a result, Cardiff had the third highest gross debt in the Premier League with their £135 million only behind Manchester United (following the Glazers’ leveraged buy-out) and Arsenal (to finance the Emirates Stadium construction). Of course, both those clubs also had substantial cash balances (Arsenal £208 million, United £66 million), while Cardiff only held cash of around £1 million.

In fairness to Tan, he and his colleagues have put a colossal amount of money into Cardiff City, around £142 million by my calculations, split between £130 million of loans and £12 million of new share capital. This has covered large operating losses, while funding player purchases and investment in infrastructure, so that the books are balanced from a cash perspective. As Slade said, “The figures are staggering – the amount of money and support he has given this football club.”

The club’s annual report said that the Malaysian investors “will continue to support the company in the foreseeable future”, but added two important provisos, namely that “the business develops as planned” and “long-term funding is not guaranteed.” That’s not exactly an unequivocal commitment.

An additional worry might be Tan’s expanding portfolio of football clubs, as he recently added KV Kortrijk in Belgium to FK Sarajevo in Bosnia and (a minority share in) MLS franchise Los Angeles FC), though these could just as easily be used to provide talent to Cardiff in the future.

In any case, the advent of FFP should at least apply a brake to Tan’s spending in the Championship, even if he did want to again bankroll the club. Dalman recently emphasised the need for Cardiff to operate “in a viable and financially sustainable manner.”

"Complete Control"

Tan himself has observed, “Cardiff is very important to me. I have put in a lot of money there. I hope to be able to take Cardiff to the Premier League again, but we will not do it in a silly way. We will do it in a more commercially clever manner.” Some have taken this as an indication that the club might be willing to sell some of its better players over the summer with bids reportedly having been received for David Marshall, Peter Whittingham and Joe Mason.

However, it is also worth remembering that this is the last season that Cardiff will receive big money from parachute payments (£20 million), as these drop to £10 million from the next year. It might therefore be tempting to once again “speculate to accumulate”, especially as Tan does not seem like the kind of man to patiently bide his time in the Championship. Whichever strategy Cardiff opts for, the harsh reality is that there are no guarantees in football – no matter how much you spend.