For many years Fulham enjoyed a great deal of success. Funded by substantial investment from their then owner Mohamed Al Fayed, the club rose from the third tier of English football to reach the top flight and then became an established Premier League club. They finished as high as 7th one season, followed by a memorable run to the Europa League final, where they were narrowly defeated by Atletico Madrid after extra time. As Al Fayed noted, the breathtaking 4-1 victory over the mighty Juventus en route to that final was “probably the greatest game ever seen at Craven Cottage.”

That was then, this is now. In July 2013 Al Fayed sold the club to Shahid Khan, the owner of NFL side Jacksonville Jaguars, which seemed like a perfect fit at the time, but has proved fairly disastrous to date. In his brief tenure Khan has dismissed three managers (Martin Jol, René Meulensteen and the hapless Felix Magath) before confirming former Fulham stalwart Kit Symons as manager in October 2014.

Unsurprisingly, this frenetic turnover has not produced the best of results and after 13 consecutive years in the Premier League, Fulham were relegated at the end of the 2013/14 season. Not only that, but they then flirted with relegation to League One before finishing 17th in the Championship.

"Bryanstorm"

Maybe understandably, Al Fayed has criticised the efforts of the new owner, “In football you cannot be an absentee landlord, as I fear Shahid Khan is most of the time.” While it is certainly true that Khan’s trigger-happy approach has not helped matters, it should be acknowledged that he did provide a tidy sum to buy new players in his first transfer window, even if the calibre of the purchases left an awful lot to be desired.

It is also evident that he inherited an aging squad, which suffered from a lack of investment in the latter stages of the Al Fayed era. Once the Egyptian had decided to sell up, it very much looks like he did not want to invest as much as he had in previous years. So, when Fulham lost the influential trio of Clint Dempsey, Danny Murphy and Mousa Dembélé in 2012, they were not adequately replaced, which arguably started Fulham’s decline.

It might be a little harsh to lay some of the blame for the subsequent deterioration at Al Fayed’s door, given that it was his money that was behind the club’s revival in the first place, but football can be a harsh mistress – especially when the funds dry up.

Matters were no better off the pitch, as Fulham reported a hefty £33 million loss in 2013/14, considerably worse than the £2 million loss in the previous season. This took some doing, given that their revenue rose £18 million from £73 million to a record £91 million off the back of the new Premier League TV deal.

However, there were two major factors influencing the higher loss: (a) a “significant” £17 million impairment charge to reduce the value of player registrations following relegation; (b) a £21 million reduction in profits from player sales with the previous year boosted by the transfers of Dembélé and Dempsey to Tottenham.

There were also other increases in the cost base: £3 million in player amortisation; £2 million in wages; and an unexplained £6 million in other expenses, which rose 38% from £16 million to £22 million, though this might include severance payments to Jol and Meulensteen.

In fact, Fulham’s £33 million loss was the highest in the Premier League in 2013/14. Thanks to the higher TV money, 15 of the clubs in the top flight were profitable with only five clubs reporting losses. Apart from Fulham, the other four clubs that lost money were Manchester City £23 million, Sunderland £17 million, Cardiff City £12 million and Aston Villa £4 million.

Clearly Fulham’s financial results were greatly influenced by the £17 million impairment charge, which contributed half of the reported loss. To better understand the reasons for this charge, we need to look at how football clubs account for player purchases. Importantly, transfer fees are not fully expensed in the year a player is purchased. Instead, the cost is written-off evenly over the length of the player’s contract via player amortisation – even if the entire fee is paid upfront.

As an example, if a player was bought from for £10 million on a four-year deal, the annual amortisation in the accounts for him would be £2.5 million. After two years, the cumulative amortisation would be £5 million, leaving a value of £5 million in the accounts. However, if the directors were to assess the player’s achievable sales value, taking into consideration the prevailing conditions in the transfer market, as £3 million, then they would book an impairment charge of £2 million. Impairment could thus be considered as accelerated player amortisation.

From Fulham’s perspective, the 2013/14 impairment charge has definite advantages in terms of Financial Fair Play (FFP). As clubs are permitted to make far higher losses under the Premier League regulations (£105 million over three years) compared to the Championship (currently £8 million a year), it makes perfect sense to book impairment charges in the Premier League accounts. This approach has the added benefit of reducing annual amortisation charges in future years (from £2.5 million to £1.5 million in our example).

Fulham are by no means the only club to employ this fancy footwork in their accounts, though their £17 million impairment charge was only surpassed by Chelsea in 2013/14 (£19 million). The other clubs relegated that season also booked impairment charges, but much lower amounts: Cardiff City £7 million and Norwich City £2 million.

Although impairment was obviously a major reason for Fulham’s overall £33 million loss, the club cannot simply hide behind this factor. If impairment were to be excluded, Fulham would still have made a loss of £16 million, only “beaten” by Manchester City’s £23 million.

Large losses are nothing new for Fulham: in the last 10 years they have made cumulative losses of £119 million, including £54 million in the last three years alone. They have reported (small) profits just twice in this period: £2 million in 2008 and £5 million in 2011.

Even these profits were due to specific factors, mainly high profits on player sales, which were £12 million in 2008 and £14 million in 2011, though 2008 also benefited from a £10 million write-off of a loan from one of Al Fayed’s companies. The only other “double digit” profit on player sales in this period was the £22 million made in 2013, which helped restrict the loss that year to only £2 million.

Excluding these special factors and the various impairment charges, we can see that Fulham have made consistent underlying losses of £10-20 million over the years, which raises questions over their operating profitability.

Basically, without the benefit of profitable player sales, Fulham are likely to struggle financially. That can be clearly seen in 2013/14 when Fulham’s profits from this activity were only £300,000. In contrast, three of the four most profitable clubs that season made substantial money from this activity: Tottenham £104 million (thanks to Gareth Bale’s transfer to Real Madrid), Southampton £32 million and Everton £28 million. The exception was Manchester United, largely thanks to their commercial excellence.

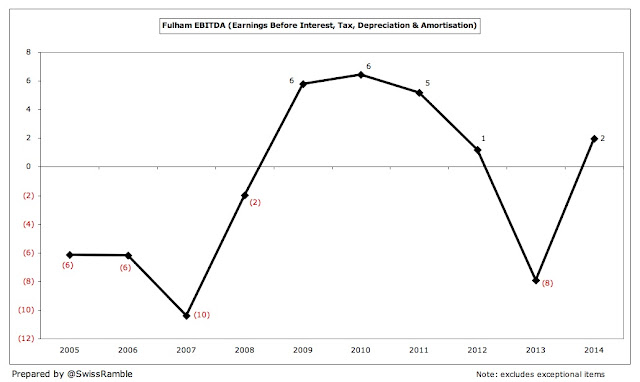

In this way, Fulham’s EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxation, Depreciation and Amortisation) had been on a declining trend from £6 million in 2010 to minus £8 million in 2013 before rising to £2 million in 2014 due to the new TV deal.

The club’s accounts specifically made mention of this £2 million operating profit, but the plain reality is that it was still the lowest in the Premier League. In fairness, few people would expect them to compete with the likes of Manchester United £130 million and Manchester City £75 million, but Fulham were a full £7 million behind WBA, the club with the next smallest operating profit.

It’s not entirely clear how this reconciles with Khan’s promise to “manage the club’s financial and operational affairs with prudence and care.”

Fulham’s revenue rose £18.3 million (25%) from £73 million to £91.3 million in 2014, almost entirely due to the new TV deal, which was up £18 million. Commercial income was up £1.3 million (12%) from £11.1 million to £12.3 million, while gate receipts were slightly down at £12.3 million.

In fact, broadcasting has been the main driver of Fulham’s revenue growth over the years, linked to the new three-year Premier League deals starting in 2008, 2011 and 2014, so TV was responsible for £44 million of the £52 million increase since 2007. That said, there has also been some reasonable growth in other revenue streams: commercial was up £5 million (65%), while gate receipts were £4 million (41%) higher.

Fulham’s Europa League experience has had an impact, most notably in 2010 when their exploits earned £12.5 million. This competition was also worth £3.4 million in 2012 after Fulham qualified via the Fair Play table.

Despite this revenue growth, Fulham’s £91 million left them as the 16th highest in the Premier League in 2013/14, just behind Norwich City £94 million and only ahead of Crystal Palace £90 million, WBA £87 million, Hull City £84 million and Cardiff City £83 million. In other words, the three relegated clubs were all in the bottom six in revenue terms, though this is a bit “chicken and egg”, as the Premier League TV distributions partly depend on where a team finishes in the league.

In their annual Money League survey, Deloitte noted that every Premier League club is in the top 40 revenue earners worldwide, which sounds very impressive, if it were not for the fact that this does not help much domestically. For example, five English clubs earn more than £250 million a season with Manchester United leading the way at £433 million – or nearly five times as much as Fulham. This really highlights the magnitude of the challenge for the smaller clubs in the Premier League.

Nearly three-quarters (73%) of Fulham’s revenue comes from television, up from the previous season’s 68%, due to the new deal. Only 14% was derived from commercial income and 13% from gate receipts.

The club notes this as a risk in the accounts, but incredibly eight Premier League clubs have an even higher reliance on TV money than Fulham with Crystal Palace and Swansea City both earning around 82% of their revenue from broadcasting.

Fulham’s share of the Premier League television money rose 40% (£18 million) from £45 million to £63 million in 2013/14. This is based on a fairly equitable distribution methodology with the top club (Liverpool) receiving around £98 million, while the bottom club (Cardiff City) got £62 million.

Most of the money is allocated equally to each club, which means 50% of the domestic rights (£21.6 million in 2013/14), 100% of the overseas rights (£26.3 million) and 100% of the commercial revenue (£4.3 million). However, merit payments (25% of domestic rights) are worth £1.2 million per place in the league table and facility fees (25% of domestic rights) depend on how many times each club is broadcast live.

In this way, Fulham falling from 12th to 19th in the league directly cost them £8.6 million, as their merit payment was only worth £2.5 million, compared to the £11.1 million that 12th placed Swansea City received. What is also clear is that Fulham’s distributions have been restricted by being broadcast live no more than 10 times, which is the contractual minimum, receiving £8.6 million, compared to, say, Aston Villa’s £13.1 million for being shown live 16 times.

Of course, in 2014/15 Fulham will receive a lot less TV money in the Championship, amounting to around £28 million. This will comprise a parachute payment of £25 million and a Football League distribution of £1.7 million plus money for cup runs, live matches, etc. That would mean a reduction in TV money of £39 million.

That might sound bad, but most clubs in the second tier receive just £4 million from television, regardless of where they finish in the league, comprising the £1.7 million from the Football League pool and a £2.3 million solidarity payment from the Premier League. Note: clubs receiving parachute payments do not also receive solidarity payments.

Parachute payments are currently worth £65 million over four seasons (£25 million in year 1; £20 million in year 2; and £10 million in each of years 3 and 4) and have a big influence on a club’s finances in the Championship.

These payments will very likely increase in 2016/17 when the recent blockbuster Premier League TV deal comes into play, but so will the distributions in the top flight. My estimate is that the bottom club’s share will rise by £30 million to £92 million, while the year 1 parachute will only increase by £11 million to £36 million. This means that the gap to the Premier League would further increase: from £35 million (£62 million minus £27 million) to an amazing £54 million (£92 million minus £38 million). It is therefore imperative for Fulham to bounce back as soon as possible.

Clearly, being in the Championship will have a huge impact on Fulham’s revenue, as acknowledged by the club: “Following the relegation of Fulham football club from the Premier League, the group is forecasting a significant reduction in income during the 2014/15 financial year and, if the club is unable to secure promotion at the end of that year, a reduction in future years.”

On top of the estimated £39 million fall in broadcasting, there will also be reductions in gate receipts and commercial. Based on cheaper tickets and smaller attendances (partially offset by more games in the Championship), I would expect gate receipts to fall by a third (£4 million) from £12 million to £8 million, while commercial income is likely to drop by at least 25% (£3 million) from £12 million to £9 million, depending on whether sponsorship deals have relegation clauses.

That would produce a total reduction in revenue of £46 million from £91 million to £45 million, though this is still likely to have been one of the highest in the Championship last season (along with Norwich City), which makes the under-performance all the more disappointing. To give an idea of the figures in the second tier, in 2013/14 QPR had the highest revenue with £39 million, followed by Reading £38 million and Wigan Athletic £37 million.

Given the team’s relegation form, gate receipts held up pretty well in 2013/14, falling just 1% (£0.2 million) from £12.5 million to £12.3 million, which was the 13th highest in the Premier League.

That’s a fairly elevated position, considering that Fulham’s average attendance of 24,977 was only the 17th highest in the top flight, implying that the ticket prices are on the high side. For example, Aston Villa only earn £500,000 more revenue than Fulham, despite their attendance being nearly 50% higher at 36,081.

Indeed, a BBC survey on ticket prices confirmed that Fulham had the most expensive season tickets in the Championship at £839, even though they did significantly cut their cheapest season tickets to £299. To be fair, Fulham have announced that adult season tickets will be reduced by 15% for the 2015/16 season, while junior season tickets have been slashed to half-price.

Something had to be done to address the steep fall in attendances, which have dropped by 27% (6,700) to 18,276 in the Championship. In the last few seasons in the top flight Fulham have consistently attracted crowds of around 25,000, restricted by the 25,700 capacity of Craven Cottage.

This is why the club is looking at the redevelopment of the Riverside Stand, which would not only increase the capacity to around 30,000, but also improve the lucrative corporate hospitality facilities. It is unclear whether this will be pursued in the Championship, though planning permission has been secured.

Commercial income rose 12% (£1.3 million) from £11.1 million to £12.3 million, largely due to the change in shirt sponsor from FXPro to Marathonbet, but this was still among the lowest in the Premier League. Clearly, clubs like Manchester United £189 million and Manchester City £166 million are out of sight, but Fulham could aspire to match, say, Stoke City – at least when they are in the top flight.

Although Fulham have made progress commercially, there is still much to do in this area, with Khan acknowledging the need to grow the brand. The Europa League exposure was not fully exploited in the past, so it will be a real test of his executive team in the Championship, especially as the shirt sponsorship is up for renewal this season.

The £5 million earned from Marathonbet was in the top 10 deals in the Premier League, but it may well be worth less in the second tier. Similarly, there may be relegation clauses in other agreements, such as the long-term kit supplier partnership with Adidas.

The wage bill was up 3% (£2 million) from £67 million to £69 million, though the underlying increase was probably higher on the assumption that bonus payments were cut following relegation. This is another drawback of having a squad full of old players, as they tend to be on a higher salary than younger alternatives. Following the revenue growth, the wages to turnover ratio improved from a frankly unsustainable 91% to a slightly more palatable 75%.

However, that ratio was still the 2nd highest in the Premier League, just behind WBA, and way above the average of 60%. In short, Fulham’s wage bill of £69 million was simply too large relative to the club’s revenue – and indeed the team’s performance on the pitch.

In terms of wages, Fulham were solidly mid-table (11th place), above teams like West Ham (£64 million), Swansea City (£63 million), Southampton (£63 million) and Stoke City (£61 million), who all comfortably outperformed them. In fact, they were only £1 million below 8th placed Sunderland. Essentially, Fulham spent more than enough money to survive, but just spent it very badly.

Although every manager would happily spend more money, the reality is that Fulham’s demise should not have happened based on their wage bill, which has steadily risen over the years. To reinforce this point, the comparison with Aston Villa is instructive: five years ago their wage bill was £30 million less than the Midlands, club, but the difference had all but disappeared by 2014.

In 2014/15 the wage bill should have been cut considerably in the Championship, not least because the club has confirmed that player contracts include relegation clauses.

After many years of fairly sizeable player investment, there was a distinct reduction in the latter stages of the Al Fayed reign with £12 million of net sales between 2010 and 2013. Since Shahid Khan’s arrival in 2013 Fulham have once again splashed the cash with net spend of £27 million in the last two years.

Unfortunately many of these purchases have not worked out with £12 million record signing Kostas Mitroglou returning to Olympiacos after just 3 appearances, while Maarten Stekelenburg has also been loaned to Monaco.

The club explained the renewed spending: “our immediate and over-riding priority is to gain promotion back to the Premier League and we will continue to invest in the playing squad in order to achieve this aim as quickly as possible.”

In fact, Fulham have the highest net spend over the last two years of any club competing in the Championship. Granted, this comparison has to be treated with some caution, as the figures are distorted by clubs that were in the Premier League the previous season, but Fulham supporters would be entitled to expect a better return on this level of investment.

As at 30 June 2014 Fulham’s gross debt was £26 million, which was an unsecured loan from Shahid Khan via the wonderfully named Cougar BidCo London Limited. There is no fixed repayment date, but interest is payable at 0.25% above LIBOR. In addition, Fulham owed other football clubs £16 million in outstanding transfer fees and they had net expenditure of £11.7 million after the accounts closed, largely for striker Ross McCormack.

The big story here is the £212 million of loans that Al Fayed converted to equity in 2012, effectively leaving the club debt-free, which was a very generous gesture. Little wonder that the Fulham Supporters’ Trust felt it “important to recognise the immeasurable contribution our outgoing chairman has made to he history of our great club.” To place that into context, at one stage Fulham had the 3rd highest debt in England, only behind Manchester United (following the Glazers’ leveraged buy-out) and Arsenal (to finance the Emirates Stadium construction) – all owed to Al Fayed.

Although it’s very good news that Fulham’s debt has been reduced, it is worth noting that the overall debt (including transfer fees) is once again rising. In addition, their cash balance fell from £14 million to just £2 million, one of the lowest in the Premier League.

Fulham have clearly strived to be cash flow positive from operating activities, though they have not met this objective in the last two years. However, any investment in players or infrastructure has had to be financed by loans from the owners, Al Fayed up to 2013 and Khan since then. Since 2007 the club spent £66 million on players and £21 million on capital expenditure plus £8 million on interest, which was funded by £89 million of owners’ loans.

This will be a tricky balance for Fulham going forward, as they will be constrained by FFP regulations. Under the existing Championship rules, clubs are only allowed a maximum annual loss of £8 million (assuming that any losses in excess of £3 million are covered by injecting equity). Even though FFP exclude certain costs, such as youth development, promotion-related bonuses and depreciation on fixed assets, it is clear that Fulham will have to significantly cut costs to be compliant.

The current rules apply for the 2014/15 and 2015/16 seasons (though the maximum allowed loss is increased to £13 million from the second season), but will change from the 2016/17 season to be more aligned with the Premier League’s regulations, e.g. the losses will be calculated over a three-year period up to a maximum of £39 million.

"Danish Dynamite"

FFP encourages clubs to invest in youth, which Khan has frequently stressed is hugely important to Fulham’s future: “player development will be at the core of our foundation at Fulham as we build a club system that grooms youngsters while creating and stocking a pipeline of talent into our first team.” If it works, this strategy would also provide players that can be profitably sold to other clubs, which is pretty much a necessity for a club of Fulham’s size to be sustainable.

Academy director Huw Jennings used to perform a similar role at Southampton’s highly regarded equivalent, so there is much cause for optimism with the youth system, as evidenced by the emergence of talented prospects such as Dan Burn and Patrick Roberts. It is always difficult to know when to blood young players, but at least Fulham now have the right structure in place.

Relegation and the subsequent inability to bounce straight back have undoubtedly been a shock to the system, but Khan is eager to improve: “Our commitment to raising our game is uncompromising at every level of the club, and we’re eager to turn the page.”

"How will Hugo?"

Whether that can be achieved is a big question, as there are still many issues to resolve, including the need to find a better balance between old and young players in the squad, not to mention what to do with some of the more misguided acquisitions.

It is debatable whether Kit Symons is the right man for the job, though his relative inexperience might be compensated by his undoubted enthusiasm, typified by his recent observation that “promotion is not unrealistic at all.”

That’s easier said than done, of course, and many Fulham supporters would consider promotion to be unlikely, given the scale of the rebuilding required, but a degree of (level-headed) positive thinking surely cannot hurt if the club is to have any hope of returning to the top flight.

0 comments:

Post a Comment