Sheffield Wednesday are one of those clubs with a fine history that these days find themselves playing in the Championship. Wednesday spent most of the 80s and 90s in the top flight of English football, but have not been in the Premier League since 2000 and won the last of their First Division titles back in 1930.

Indeed, in recent times they actually spent two seasons in League One, England’s third tier, before promotion back to the Championship in 2012. Since then, they have not really threatened the promotion or play-off places, but there is now cause for a degree of optimism in the steel city following the arrival of new Thai owner Dejphon Chansiri.

His family owns the world’s largest producer of canned tuna, while Dejphon himself has a thriving property and construction company in Thailand. He acquired Wednesday for £37.5 million in January and has targeted promotion to the Promised Land of the Premier League within two years. He has already claimed to have cleared the club’s debts and given new head coach Carlos Carvalhal substantial backing in the transfer market.

"My name is Lucas"

Chansiri bought the club from Milan Mandaric, who had effectively saved Wednesday from going into administration when he bought the club for a nominal £1 in December 2010, but importantly negotiated terms to wipe out the club’s significant debts. In particular, he persuaded the Co-operative Bank to settle their £23 million debt for a £7 million payment.

Wednesday had faced a series of winding-up petitions from HMRC between July and November 2010 for unpaid VAT and payroll taxes, which were only withdrawn following Mandaric’s intervention.

Wednesday’s problems on the pitch went hand in hand with their financial difficulties, as Mandaric explained: “The decline of this great club can be traced back over the past decade. Both on and off the field mismanagement has seen a true footballing institution teeter on the edge of the financial abyss.”

"Tommy, can you hear me?"

Given these issues, Mandaric adopted a somewhat more cautious approach to spending: “I will not gamble with the long-term future of Sheffield Wednesday, this club has already flirted with financial oblivion far too closely in recent seasons.”

However, as the auditors noted in the annual accounts, the club continued to rely on the financial support of its parent company, which was “not legally binding and dependent on the intentions of the owner.” This lead to them noting a “material uncertainty which may cast significant doubt about the company’s ability to continue as a going concern.”

Strong stuff, but many clubs in the Championship rely on the goodwill of their owners and Wednesday are no exception. The hope would be that Chansiri continues to provide the club with the financial support required at this level.

Although Wednesday’s financial position is not ideal, in truth it’s not too bad for a Championship club, even though they reported a £5.6 million loss in 2013/14, the last season for which figures are available.

That said, the loss did increase from £3.7 million the previous season, as revenue dropped £1.1 million (7%) to £13.9 million, mainly due to a reduction in match receipts and commercial match day income; while the wage bill rose £0.6 million (5%) to £12.5 million, following an increase in player salaries and management costs. There were £0.1 million reductions in both depreciation and other expenses, but interest payable shot up by £0.3 million to £0.5 million.

Mandaric justified the loss when referring to “the difficulty of operating our club in the Championship whilst trying to remain competitive.” In fairness, Wednesday’s loss is quite small compared to most other clubs in this division, placing them a creditable 8th in the profit league.

As Mandaric observed, “we’re losing money, but not as much as some clubs”. That’s evident when you consider the stratospheric losses posted by the likes of Blackburn Rovers £42 million, Nottingham Forest £23 million, Leicester City £21 million, Middlesbrough £20 million and Leeds United £20 million.

In fact, the only clubs to make money in the Championship were Blackpool (with their highly dubious model), Wigan Athletic and Yeovil Town – and they have all since been relegated. In 2013/14 losses were reported by 21 of the 24 clubs – in stark contrast to the Premier League where the new TV deal, allied with wage controls, has led to a surge in profitability.

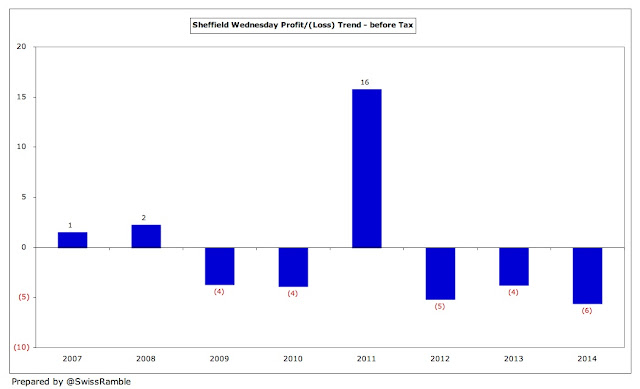

Wednesday have consistently reported smallish losses over the past few years. The last time that they made an accounting profit was in 2011, which was boosted by a £21.4 million (non-cash) credit after the former owner agreed to waive all amounts owed. Excluding this exceptional item, the club would have made a £5.6 million loss instead of a £15.8 million profit.

After that adjustment, Wednesday would have made an aggregate loss of £27.8 million in the last six seasons, averaging a £4.6 million deficit each year. Mandaric acknowledged that “losses of this amount will need to be reduced in the future and ultimately I would hope the club can be self-supporting.”

Other once-off items to hit Wednesday’s books include £1.4 million in 2012 due to bonus costs relating to promotion back to the Championship and the change in football management during the season. There was another £0.25 million paid the same season to the Co-operative Bank for a promotion-related clause in their debt settlement.

Profit on player sales can also improve the bottom line, but this has not really been the case at Wednesday. The last time they made any meaningful money from transfers was back in 2008 £3.3 million, mainly due to the sale of Chris Brunt to WBA and Glenn Whelan to Stoke City, and 2007, thanks to Madjid Bougherra’s move to Charlton Athletic.

Since then they have made just £2.2 million in six seasons, including only £0.3 million in 2013/14. Although few Championship clubs make big profits on player sales with only two earning more than £5 million in 2013/14 (Wigan Athletic and Bournemouth), Wednesday’s was still among the lowest.

Player trading is by no means the only issue at Wednesday, as the underlying business is loss making. The club has made operating losses in each of the last six years, though there has been some recovery in the Championship to £3-4 million.

Unsurprisingly the operating losses peaked at £7 million in League One in line with lower revenue, as described by the club: “The cost base, in common with other football clubs, is relatively fixed in the short-term, hence unfavourable movements in revenue, including those arising from below budget on pitch performance, can lead to significant variation in profits.”

Revenue fell by £1 million (7%) from £14.9 million to £13.9 million, largely due to decreases in match receipts of £0.7 million (11%) to £5.5 million and commercial income of £0.6 million (13%) to £3.9 million, slightly offset by a £0.2 million (5%) increase in broadcasting revenue to £4.5 million.

As you would expect, revenue was lower in League One, declining by £4.5 million to £9.4 million in 2011. As the club put it, “A mixture of relegation, supporter dissatisfaction and the general economic downturn saw falls in revenue across all areas of the business.”

The other side of that coin is that revenue has increased since promotion, but only by £2.9 million. The growth is entirely due to the better TV distribution deal in the Championship, which has increased broadcasting revenue by £3.3 million. In contrast, commercial revenue has only increased by £0.1 million, while match receipts are actually down £0.5 million.

Following the reduction in 2013/14, Wednesday’s revenue of £13.9 million was only the 15th highest in the Championship, a long way behind the top three clubs: QPR £39 million, Reading £38 million and Wigan Athletic £37 million. In fact, six clubs earned more than £30 million that year. Of course, to a large extent, this simply demonstrates the importance of parachute payments for those clubs relegated from the Premier League.

If these were to be excluded, Wednesday would move up to a more healthy 10th place in the Championship revenue league, but even so their £14 million would still be a long way behind Leicester City £31 million, Leeds United £25 million, Brighton £24 million and Derby County £20 million. Given these numbers, Wednesday’s mid-table performance could be regarded as essentially par for the course.

Much of Wednesday’s revenue performance is driven by match day receipts, which account for 40% of their total revenue, followed by broadcasting 32% and commercial 28%.

In fact, only four Championship clubs have a greater reliance on match day receipts than Wednesday: Charlton Athletic 50%, Nottingham Forest 44%, Brighton and Hove Albion 43% and Millwall 41%.

Arguably Wednesday’s match day revenue is even higher, as their accounts also include £1.8 million of commercial match day income, but I have classified this within commercial revenue, as this is consistent with the £3.9 million listed in the club’s turnover figures for total commercial activities.

Either way, the importance of match day revenue to Wednesday is clear, so the £0.7 million (11%) reduction from £6.2 million to £5.5 million in 2013/14 is concerning, especially as this was as high as £6.5 million before relegation to League One in 2010. Revenue here is partly influenced by progress in cup competitions, which helped keep the figure high in 2010, but the 2014 fall was essentially due to a 12% decrease in the average attendance from 24,078 to 21,274.

Even so, Wednesday’s match day revenue of £5.5 million was the 9th highest in the Championship. To put this into perspective only three clubs generate more than £7 million (Brighton £10.4 million, Leeds United £8.6 million and Nottingham Forest £7.2 million).

Even more impressively, Wednesday’s average attendance of 21,274 was the 6th highest in the Championship in 2013/14 and climbed to 21,993 last season. Although this is a little disappointing, considering the 24,078 average achieved in the first season back in the Championship, there is little doubting the potential here.

As a recent example, you only have to look at the 38,000 crowd that watched the final home game in the League One promotion season. This nearly filled the 40,000 capacity at Hillsborough, one of the largest grounds in the country.

Wednesday had kept “Early Bird” season ticket prices static for many seasons, but have introduced a new match day pricing structure for the 2015/16 season, which features a number of steep hikes in some prices.

Whether this is the right move, especially given that South Yorkshire is the fifth most impoverished area of the country, is obviously debatable, but the objective is to help fund a promotion drive by maximizing revenues streams. This move is understandable to an extent, but the fans are only likely to be placated if promotion is delivered.

Chansiri justified the price increase as follows: “In the bigger picture, if we are to achieve our ultimate aim of promotion, we must embark on this journey together. I will lead that journey as your chairman, but I need as much help as possible along the way. Budgets must be achieved, we must work within the constraints of Financial Fair Play, and we do not have the benefit of parachute payments, unlike a significant number of our peers in the Championship, each of whom are aiming for the same destination. As our costs increase, so too must our revenues across the business.”

In 2013/14 Wednesday’s broadcasting revenue was £4.5 million, which was in line with the majority of Championship clubs, who receive the same annual sum for TV, regardless of where they finish in the league. This amounts to just £4 million of central distributions: £1.7 million from the Football League pool and a £2.3 million solidarity payment from the Premier League. Other television money is dependent on whether a team reaches the play-offs; cup runs and the number of times a club is broadcast live.

However, the major impact of parachute payments is once again highlighted in this revenue stream, greatly influencing the top eight earners, though it should be noted that clubs receiving parachute payments do not also receive solidarity payments.

Looking at the Premier League television distributions, the massive financial disparity between England’s top two leagues becomes evident with Premier League clubs receiving between £65 million and £99 million, compared to the £4 million in the Championship. In other words, it would take a Championship club more than 15 years to earn the same amount as the bottom placed club in the Premier League.

If Wednesday were to somehow gain promotion, the financial prize for returning to the Premier League would be immense. Even if a team finishes last in their first season and go straight back down, their TV revenue would increase by £61 million (£65 million less £4 million) and they would also receive a further £65-75 million in parachute payments, giving additional funds of around £130 million.

It could be even more, depending on where the club finishes in the league (with each place worth an additional £1.2 million) and how many times they are televised live (where each club is paid facility fees, with a contractual minimum of 10 games). All this is before the recent blockbuster Premier League deal that starts in 2016/17, which I estimate will be worth at least another £30 million a season. The size of the prize helps explain the behaviour of many Championship clubs, which are spending more than ever this season.

As we have seen, parachute payments make a significant difference to a club’s revenue and therefore its spending power in the Championship. Up to now, these have been worth £65 million over four years: year 1 £25 million, year 2 £20 million and £10 million in each of years 3 and 4.

However, the Premier League has recently announced changes to this structure, whereby from 2016/17 clubs will only receive parachute payments for three seasons after relegation, although the amounts will be higher (my estimate is £75 million, based on the advised percentages of the equal share paid to Premier League clubs: year 1 55%, year 2 45% and year 3 20%).

Revenue from commercial activities decreased by £0.6 million (13%) to £3.9 million in 2013/14, comprising commercial match day income £1.8 million (hit by the fall in attendances), retail and merchandising £1.5 million, catering £0.3 million and internet & other £0.2 million.

For a club with Wednesday’s history, their commercial revenue is fairly low and only the 13th highest in the Championship – though it should be noted that it is impacted by the outsourcing of the catering division in 2012.

One of Chansiri’s stated objectives is to raise the club’s commercial profile in the Far Ease, notably Thailand and Singapore. To that end, his family will act as principal shirt sponsor in 2015/16 to “illustrate to the whole of the football world our total support for this club.” It will be interesting to see how much this deal is worth, given that Leicester City’s Thai owner organized a lucrative marketing agreement with Trestellar Limited that boosted their commercial revenue to £18.6 million.

"Loovens - Building on Fire"

In 2014/15 Wednesday’s shirts were emblazoned with the Azerbaijani “Land of Fire” logo, as worn by Atletico Madrid and Lens, which had been secured by Hafiz Mammadov, who at one stage had looked like he would take ownership of the club from Mandaric. The value of this arrangement was not disclosed, beyond the fact that it was “financially significant” and a “six-figure deal”. This replaced the 2013/14 deal with WANdisco, a global software development company.

Retail sales are also expected to improve after a three-year kit deal commencing in 2014/15 was signed with Sondico, part of the Sports Direct family of brands.

The wage bill rose by 5% (£0.6 million) from £11.9 million to £12.5 million, increasing/worsening the wages to turnover ratio from 80% to 90%, though part of the growth was due to the club’s decision to change the manager (Dave Jones) in December 2013.

This means that wages have risen by £4.2 million (51%) since promotion, which is considerably more than the £2.9 million (27%) revenue growth in the same period. Nevertheless, Wednesday’s wage bill is still one of the smallest in the Championship with only six clubs below them – though one (Watford) was promoted the following season.

It was significantly lower than the likes of Leicester City, Reading, Blackburn Rovers and Wigan Athletic, whose wages were all above £30 million. QPR were even higher at £75 million, but that was simply ridiculous in the second tier.

Wednesday’s wages to turnover ratio of 90% is not great, but it is only the 14th highest in the Championship. Given the relatively low revenue, many clubs in the second tier have a dreadful wages to turnover ratio with 10 of them being more than 100%, including QPR 195%, Bournemouth 172%, Nottingham Forest 165% and Millwall 132%.

Arguably, Wednesday’s lack of spending on wages contributed to their troubles, as their wages to turnover ratios before relegation were all on the low side, even though they steadily increased their wage bill to £9.6 million in 2010. This again highlights the challenges outside the top flight.

Player amortisation has been steadily rising since promotion, but is still only £1.0 million, again one of the lowest in the Championship. To put this into perspective, the highest player amortisation was at QPR £16.6 million, Blackburn Rovers £7.2 million, Wigan Athletic £6.8 million and Nottingham Forest £5.7 million.

As a reminder, transfer fees are not fully expensed in the year a player is purchased, but the cost is written-off evenly over the length of the player’s contract via player amortisation – even if the entire fee is paid upfront. As an example, Marco Matias was bought for a reported £3 million on a four-year deal, so the annual amortisation in the accounts for him would be £750,000.

In the same way, the lack of spending in the transfer market is reflected in the balance sheet, with the value of player (intangible) assets only £1.3 million in 2014.

Given their financial difficulties, it is no surprise that Wednesday have spent very little on player recruitment: just £2.6 million gross spend in the eight seasons up until 2014/15, offset by £6.4 million of sales, giving net sales of £3.8 million. Mandaric “tried to support the manager wherever possible”, but it’s been a whole new ball game since Chansiri arrived.

On the day he was announced as the new owner, he preached prudence: “I believe that there needs to be some investments into the club, but just throwing money at it is not a guarantee of success. We need to do it in a smart and sustainable manner. Some clubs throw a whole lot of money at it in the transfer market, but are not successful.”

However, he has bankrolled some major purchases with more than £9 million spent to date this summer on 15 players, including the likes of Marco Matias, Lucas Joao, Fernando Forestieri, Rhoys Wiggins and Lewis McGugan. In the past few days, there have been rumours of big money bids for a new striker, with Ross McCormack, Jordan Rhodes, Matej Vydra and Gary Hooper all being mentioned, so the spending might not have stopped there.

This is a big change for Wednesday, whose £0.3 million net sales over the last two completed seasons (2013/14 and 2014/15) was one of the lowest in the Championship. Although this comparison has to be treated with some caution, as the figures are distorted by clubs that were in the Premier League the previous season, either because of high spend when they were in the top flight or large sales following their relegation, it is evident that Wednesday have been comfortably outspent by their rivals, so have effectively been competing with one hand tied behind their back.

Wednesday’s gross debt increased by £1.5 million to £12.7 million in 2014. Almost all of this (£11.3 million) was owed to Mandaric’s company (“The debt is not club debt, it’s my debt as far as I’m concerned”), but there was also a £1.4 million overdraft.

This is a significant improvement on the situation when Mandaric took control with the last accounts before his takeover in 2010 showing debt of £42.6 million, including £21.5 million owed to the bank. Following the Serb’s arrival, the club benefited from the £21.4 million waiver of the previous ownership’s loan and the settlement of the external debt. More recently £0.8 million of debt was converted into share capital in November 2014.

That said, the debt had been creeping up in the last four years before Chansiri’s appearance and the accounts also include £5.1 million of other loans in accruals that are not classified as net debt for some reason. To an extent, this is all irrelevant now, as it has been claimed that the club is debt free – to be confirmed when the 2014/15 accounts are published.

In addition, the club had contingent liabilities of £0.9 million, split between transfer fees of £505,000, dependent on future appearances, and loyalty bonuses of £392,000, if players are still with Wednesday on certain dates. On top of that, in the event of promotion to the Premier League before 31 May 2021, payments will become due to players, staff and loan note holders (£1.3 million) and the Co-operative Bank (£750,000).

Using Wednesday’s definition of debt, their £12.7 million was one of the lowest in the Championship, as many clubs have built up substantial debt (very largely owed to their owners) in their pursuit of promotion, especially Bolton Wanderers £195 million, QPR £185 million, Brighton £131 million, Ipswich Town £86 million, Blackburn Rovers £80 million and Middlesbrough £77 million.

Wednesday’s cash flow from operating activities has been negative since 2009, requiring funding from the owner to balance the books with £11.3 million put in by Mandaric in the last four years. Hardly any money has been spent on player recruitment (net) or capital expenditure, though £1.3 million of interest payments have been made in the last six years, including £0.5 million in 2014 alone.

The need for financial support was referenced by Mandaric when he introduced Chansiri: “His enthusiasm, his drive to win the games and, of course, financial backing will allow him to be a top chairman for this great club.” Apart from player purchases, there is a need to invest in infrastructure, such as the stadium, the pitch and the training facilities at Middlewood Road.

The 2013/14 accounts confirmed that Wednesday have complied with the new Football League rules in respect of Financial Fair Play (FFP), adding, “we remain confident that the club can continue to operate within the current FFP regulations.” The £0.8 million conversion of debt into equity in November 2014 implied that this was the amount that was required to be in line with the allowed FFP losses.

The current rules will continue to apply for the 2014/15 and 2015/16 seasons (though the maximum allowed loss is increased to £13 million from the second season), but will change from the 2016/17 season to be more aligned with the Premier League’s regulations, e.g. the losses will be calculated over a three-year period up to a maximum of £39 million. This more relaxed approach should help facilitate Chansiri’s spending plans.

"Long May you run"

FFP encourages clubs to invest in youth development, which is an area of focus for Wednesday, whose academy was granted Category Two status under the Elite Player Performance Plan (EPPP). However, there is a price to pay with a “considerable” increase in investment in the academy taking the costs above £1 million.

The concern with EPPP is that the changes in the contractual position of players under 16 might produce a situation where clubs such as Wednesday become feeder clubs, “ultimately subsidising the costs of youth development for those able to attract the best available talent without paying the true value to the club that worked so hard developing the player.”

"Under my thumb"

There is no doubt that supporters have been put through the wringer in the past few years, very nearly going all the way “from the Ritz to the rubble” as big Wednesday fans Arctic Monkeys once sang, but Chansiri’s money might just change that.

He certainly talks a good match: “I’m developing plans over the short, medium and long term to maximise the sporting potential of Sheffield Wednesday in a healthy and sustainable manner. We feel that if we make smart decisions and savvy investments that within a couple of seasons, it’s very possible to get to the Premier League.”

The owner’s dream is to celebrate Wednesday’s 150th anniversary back in the Premier League, which would mean returning to the top flight for 2017. That’s obviously very far from a done deal, but at least the Owls now have a fighting chance.

0 comments:

Post a Comment