Considering that they were playing in English football’s third tier just 13 years ago, Stoke City have come a long way. They are now an established Premier League club, enjoying their 8th consecutive year in the top flight since gaining promotion in 2008.

Not only that, but they reached their first ever FA Cup Final in 2011, where they were only defeated by Manchester City, but still qualified for Europe, as the victors took up their place in the Champions League. In 2014/15 Mark Hughes’ team repeated the previous season's feat of finishing 9th, Stoke's highest position in the Premier League era and their best finish since 1974/75.

Furthermore, Stoke have achieved this level of success even though they have modified their playing style from the rather rudimentary tactics employed under Tony Pulis to the more free-flowing approach of Hughes’ team.

This is a testament to how well run Stoke are, consistently punching above their weight, though less generous observers might argue that this is what you get for £100 million, as this is the amount of money that chairman Peter Coates has put into his local club, making good use of the wealth accumulated from his family’s gambling company, bet365.

That said, Stoke’s strategy has been a bit more subtle than Coates simply pumping in money, as the club has combined a healthy degree of financial prudence, as well as obviously benefiting from its benefactor’s generosity.

"Handling the big jets"

In fact, Stoke’s rise can be split into three distinct phases: substantial owner financing; a move towards sustainability; a return to spending, thanks to growing TV money.

First, the owner did indeed put his hand deep into his pocket to help Stoke’s push for promotion and then fund a fairly big outlay on building a decent squad, which was essential if Stoke were to achieve their main objective of securing their presence in the Premier League.

As Coates explained in 2011, “The huge investment in the playing squad over the last four years has been in my view necessary to enable Tony Pulis to assemble a group of players capable of competing at this level.”

After financing this period of consolidation, Stoke have sought self-sufficiency with a slowdown in transfer spend allowing the wage bill to grow. This process has been facilitated by a combination of the increasing Premier League television deals and the introduction of Financial Fair Play regulations, which have dampened down inflationary cost pressures, meaning the drive towards break-even has been made somewhat easier.

"With a shout"

The influx of new TV money has then allowed Stoke to attract some big names to the Potteries, including Swiss international Xherdan Shaqiri, who was purchased from Inter for a club record £12 million. Hughes noted, “It might be a big amount of money for Stoke, but I believe it will prove to be good value. The only way you can progress is to add to the quality in your squad.”

Former German international Stefan Effenberg expressed his surprise at this transfer, “I do not understand Shaqiri’s move to Stoke at all. You have been badly advised if you go there.”

Really? Welcome to the new soul vision, Stefan.

Shaqiri’s signing was further evidence of the growing economic power of the Premier League’s mid-tier clubs, built on all that lovely TV money. Indeed, his arrival at the Britannia was hot on the heels of Stoke recruiting the likes of Bojan Krkic, Ibrahim Afellay, Marko Arnautovic, Marc Muniesa and Joselu.

As Coates explained, “We are attracting great players to the club now, because we are progressing on and off the pitch and they are excited by the challenge here.”

That progress was underlined by the 2014/15 financial results with profits rising £1.9 million from £3.8 million to £5.7 million and net debt being reduced by £4.6 million to £33.2 million.

Revenue rose £1.3 million (1%) to £99.6 million, very nearly breaking the £100 million barrier for the first time, almost entirely due to an increase in TV money. Profit from player sales was only £1.7 million, but this represented a £2.9 million improvement, as Stoke lost £1.2 million from this activity the previous year.

There was a significant reduction in transfer costs, as player amortisation fell £3.9 million (24%) to £12.4 million and there was no repeat of the 2013/14 £1.7 million impairment charge (reducing the value of player assets).

On the other hand, the wage bill climbed £6 million (10%) from £61 million to £67 million, while other expenses were £2 million (14%) higher, mainly due to £2.6 million of loan fees for Victor Moses (from Chelsea) and Oussama Assaidi (from Liverpool).

Of course, most Premier League football clubs make money these days, largely on the back of the TV deals, and Stoke were just one of 15 clubs that were profitable in 2013/14 (the last season when all clubs have published their accounts).

As Coates said, “To have the richest league in the world and these losses, that’s got to be pretty stupid by any yardstick. So it’s good it’s turned round, so it should and so it should remain.”

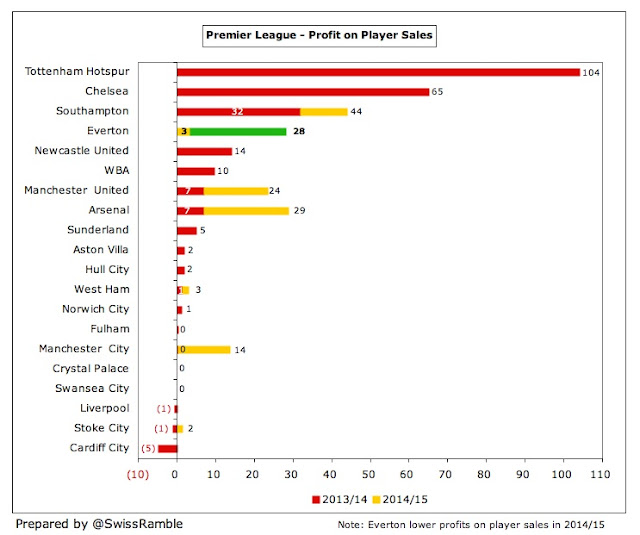

That said, Stoke’s profit of £4 million was only the 13th highest in the prior season, way behind Tottenham Hotspur £80 million, Manchester United £41 million, Southampton £29 million and Everton £28 million.

However, two points should be noted: (a) Stoke are to date one of only three clubs to have reported higher profits in 2014/15, while four clubs have registered worse results with United and Everton moving into losses; (b) the major impact that once-off player sales can have on a football club’s bottom line.

To reinforce this last point, in 2014/15 Southampton made £44 million from player sales, mainly due to the transfers of Adam Lallana and Dejan Lovren to Liverpool plus Calum Chambers to Arsenal, while the previous season saw Tottenham Hotspur make an amazing £104 million (largely from the mega sale of Gareth Bale to Real Madrid) and Chelsea £65 million (David Luiz to Paris Saint-Germain).

In stark contrast, Stoke were the second worst in the Premier League at making money from this activity in 2013/14, only ahead of Cardiff City, actually losing £1.2 million on player sales. This did improve in 2014/15, but they still made just £1.7 million from selling Cameron Jerome to Norwich City, Michael Kightly to Burnley and Ryan Shotton to Derby County.

Stoke have only recently moved to profitability with £10 million being made in the last two seasons, which Coates described as “a big turnaround”. The 2013/14 profit was the first time that the club had made a profit since 2008/09, when they registered a small surplus of £0.5 million in their first season back in the top flight.

In fact, in the eight seasons leading up to 2013/14 the club had made cumulative losses of £64 million. In fairness, nearly half of that (£31 million) came in 2012/13 as Stoke invested heavily to ensure that they remained in the Premier League in order to benefit from the new TV deal.

Many clubs have effectively been subsidising their underlying business with profitable player sales, but this has not been the case at Stoke. In the last 10 years, the club has only made £13 million from player disposals, which could either be considered as a sign that the club has tried to keep its squad together or that it has had no players that other clubs wish to buy.

Either way, this lack of profitable player sales has obviously had a big adverse effect on their financial results, though this will change in the 2015/16 figures with the sales of Asmir Begovic to Chelsea, Steven N’Zonzi to Sevilla and Robert Huth to Leicester City. The accounts state that the club has received (initial) sales proceeds of £14.9 million for players sold since the balance sheet with net book value of £1.5 million, which would imply profits of £13.4 million.

It is worth exploring how football clubs account for transfers, as it can have such a major impact on reported profits. The fundamental point is that when a club purchases a player the costs are spread over a few years, but any profit made from selling players is immediately booked to the accounts.

So, when a club buys a player, it does not show the full transfer fee in the accounts in that year, but writes-down the cost (evenly) over the length of the player’s contract. Therefore, if Stoke spent £15 million on a new player with a 5-year contract, the annual expense would be only £3 million (£15 million divided by 5 years) in player amortisation (on top of wages).

However, when that player is sold, the club reports straight away the profit on player sales, which essentially equals sales proceeds less any remaining value in the accounts. In our example, if the player were to be sold 3 years later for £18 million, the cash profit would be £3 million (£18 million less £15 million), but the accounting profit would be much higher at £12 million, as the club would have already booked £9 million of amortisation (3 years at £3 million).

This is all horribly technical, but it does help explain how some clubs can spend big in the transfer market with relatively little immediate impact on their reported profits.

Notwithstanding the accounting treatment, basically the more that a club spends, the higher its player amortisation. Thus, Stoke’s player amortisation surged from just £1 million in 2007 to a £22 million peak in 2013, reflecting the years of big spending in the transfer market, but has fallen back in the last two years to £12 million as the taps have been turned off.

However, Stoke’s financial results have also been influenced by the £13 million of impairment charges they have booked since 2009. This happens when the directors assess a player’s achievable sales price as less than the value in the accounts.

In our example, if the player’s value were assessed as £4 million after 3 years instead of the £6 million in the accounts, then they would book an impairment charge of £2 million. Impairment could thus be considered as accelerated player amortisation. It also has the effect of reducing the annual player amortisation going forward.

In any case, Stoke’s player amortisation is one of the lowest in the Premier League and is obviously miles behind the really big spenders like Manchester United (£100 million), Chelsea (£72 million) and Manchester City (£70 million). However, it should increase from next year, reflecting Stoke’s return to spending in the transfer market.

The scant purchases beforehand, allied with the impairment policy, mean that player values on the balance sheet have declined from £33 million in 2012 to just £14 million in 2015, though the accounting treatment understates the value of Stoke’s squad, as it does not fully reflect the market value of its players.

Given all the accounting complexities arising from player trading, clubs often looks at EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxation, Depreciation and Amortisation) for a better understanding of how profitable they are from their core business. The good news is that Stoke’s EBITDA shot up to £23 million in 2014, though it did fall back to £17 million last season.

Once again, this highlights the impact of the new TV deal in 2014, as the combined £40 million of EBITDA in the last two seasons is nearly twice as much as the club delivered in the previous seven seasons.

This is pretty good, but at the same time helps to outline the challenge for clubs like Stoke, as the EBITDA at the leading clubs is significantly higher, despite their larger wage bills: Manchester United £120 million, Manchester City £83 million, Arsenal £64 million, Liverpool £53 million and Chelsea £51 million.

Stoke’s revenue has grown by £32 million (47%) from £68 million in 2011 to just under £100 million in 2015, though virtually all of that increase is attributable to the TV deals, as broadcasting is up £32 million (70%) to £77.4 million. In the same period, commercial income has risen by only £1 million (8%) from £13.6 million to £14.6 million, while gate receipts have actually fallen £0.9 million (11%) from £8.5 million to £7.6 million.

To be fair, 2011 was boosted by successful domestic cup runs, which helped gate receipts and merchandising sales, while the following year was inflated by £4.5 million generated from the Europa League run.

Stoke’s achievement in finishing 9th in the Premier League is really put into perspective when you compare their revenue to other clubs: in 2013/14 their revenue of £98 million was the 14th highest in the top tier.

Things are unlikely to be any better in 2014/15, as Stoke’s tiny revenue growth of £1.3 million is one of the smallest reported to date: Arsenal £31 million, Southampton £8 million, West Ham £6 million, Manchester City £5 million and Everton £5 million.

Furthermore, Stoke’s revenue of £100 million is still a lot lower than the Champions League elite, e.g. the top four clubs all earn well above £300 million: Manchester United £395 million, Manchester City £352 million, Arsenal £329 million and Chelsea £320 million.

On the bright side, Stoke now have the 30th highest revenue in the world, according to the Deloitte Money League. This allows Stoke to pay higher wages than famous clubs such as Ajax and Lazio. In short, money talks, tradition walks.

When Shaqiri signed, he said, “It was always my dream to come to the Premier League, because I love this league and I love this country.” Fair enough, but the size of his pay cheque might just have swayed his decision.

The problem is that these additional riches do not help Stoke much domestically, as there are no fewer than 14 Premier League clubs in the world’s top 30 clubs by revenue (and all of them are in the top 40). As Coates pointed out, “You can argue which league in Europe is the best, but ours is the most competitive.”

Clearly, TV money is the main driver behind Stoke’s new standing, contributing an incredible 77% of the club’s total revenue. Commercial income accounts for 15%, while gate receipts are worth only 8%.

This might sound very worrying, but this is fairly common in the Premier League. For example, in 2013/14 four clubs actually had a greater reliance on TV money than Stoke, getting more than 80% of their revenue from broadcasting, namely Crystal Palace, Swansea City, Hull City and WBA.

In 2014/15 Stoke’s share of the Premier League TV money rose 3% from £76 million to £78 million. The distribution of these funds is based on a fairly equitable methodology with the top club (Chelsea) receiving £99 million, while the bottom club (QPR) got £65 million.

Most of the money is allocated equally to each club, which means 50% of the domestic rights (£22.0 million in 2014/15), 100% of the overseas rights (£27.8 million) and 100% of the commercial revenue (£4.4 million). However, merit payments (25% of domestic rights) are worth £1.2 million per place in the league table and facility fees (25% of domestic rights) depend on how many times each club is broadcast live.

In this way, Stoke are disadvantaged by being shown live just nine times, which was only more than two relegated clubs (Hull City and Burnley) and Leicester City, but less than many clubs that finished below them in the league.

As an example, Newcastle finished in 15th place, but were broadcast live 20 times, which “earned” them £16.2 million of facility fees, i.e. £7.4 million more than Stoke’s £8.8 million (the minimum guaranteed to any club, regardless of whether they are on TV fewer than 10 times). As Coates put it, “We suffer from being what I would call an unfashionable club.”

The blockbuster new TV deal starting in 2016/17 only reinforces the need to stay in the Premier League. My estimates suggest that Stoke would receive an additional £35 million under the new contract, increasing the total received to an incredible £113 million.

This is based on the contracted 70% increase in the domestic deal and an assumed 30% increase in the overseas deals (though this looks to be on the conservative side, given some of the deals announced to date). Of course, if they were to finish higher in the league table, they would earn even more.

Stoke might also reasonably target European qualification, which could bring in additional revenue. That might feel a touch unrealistic, but they did qualify for the Europa League in 2011/12, when they were the only British club to make it out of the group stage before being eliminated by Valencia.

This adventure only produced €3.5 million in prize money, though Everton did earn €7.5 million last season for reaching the last 16. The big money is obviously in the Champions League with English clubs averaging €39 million in 2014/15 and is getting higher, as the new TV deal from the 2015/16 season is worth an additional 40-50%, thanks to BT Sports paying more than Sky/ITV for live games.

Gate receipts dropped slightly from £7.7 million to £7.6 million, thus remaining one of the lowest in the Premier League, despite average attendance rising from 26,134 to 27,081. At the other end of the spectrum, Arsenal and Manchester United both earn around £100 million of match day revenue, which works out to around £3.7 million a match. In other words, they generate almost as much as Stoke’s annual gate receipts in just two matches.

The low revenue is actually a reflection of Stoke’s laudable approach to ticket prices, which in 2015/16 were frozen for the eighth year in succession. According to the BBC Price of Football survey, Stoke have the cheapest season ticket in the Premier League at just £294.

Not only that, but they also have 10,000 season tickets priced between £344 and £359, which means that no other club offers as many seats in that price range. Furthermore, fans aged under 11 are charged just £38 in the family area when purchased with an adult season ticket.

Stoke’s policy was outlined in the 2012 accounts: “The tremendous atmosphere at the Britannia Stadium was once again an influential factor in our home record remaining so good. This underlines the importance of our strategy to fill the ground to capacity as often as possible.”

This praiseworthy attitude looks set to continue, as Coates explained when describing the new TV deal as “an opportunity to make sure some supporters benefit from then kind of money we’re getting from the media.”

Stoke have secured planning permission to expand the 27,700 capacity of the Britannia Stadium to around 30,000 by building in the scoreboard corner, but they will only commit to this work when they are sure that they could regularly sell the 2,500 extra tickets.

Given the increase in attendance in 2014/15 (after two years of decreases), followed by a rise in season ticket sales for 2015/16, maybe this is the time to invest. Last season, Stoke’s attendance was one of the lowest in the top flight, held back by the limited capacity of the Britannia. It was only ahead of six clubs, including the three that were relegated (Hull City, Burnley and QPR).

Commercial income rose 2% (£0.2 million) to £14.6 million, largely due to growth in conferencing and hospitality (£0.3 million to £3.7 million) and retail and merchandising (£0.2 million to £2.3 million), though there were falls in sponsorship and advertising (£0.2 million to £7.5 million) and other operating income (£0.1 million to £1.2 million).

Again, Stoke’s commercial income is dwarfed by the leading clubs, e.g. the two Manchester clubs grew their commercial revenue again in 2014/15: United to £196 million and City to £173 million.

That said, Stoke’s £15 million is on a par with clubs like Sunderland and Norwich, while being ahead of the likes of West Brom, Southampton, Swansea City and Crystal Palace. Nevertheless, the onus is on the club to “maximise the commercial opportunities that our Premier League status presents locally, nationally and internationally, due to the global profile of the best league in the world.”

Since 2012 Stoke’s shirt sponsorship has been with bet365, reportedly worth £3 million a season (though listed at only £2 million in the accounts), “further underlining the owner’s long-term commitment to the club”. This replaced the agreement with Britannia, which had been on the shirts for 15 years, making it one of the longest sponsorship agreements in English football.

Of course, this deal is a long way behind the “big boys”: Manchester United – Chevrolet £47 million, Chelsea – Yokohama £40 million, Arsenal – Emirates £30 million, Liverpool – Standard Chartered £25 million and Manchester City – Etihad Airways £20 million. Of more concern, it has also been overtaken by Crystal Palace (£5 million), Sunderland (£5 million) and Swansea City (£4 million).

From the 2015/16 season Stoke’s kit deal is with New Balance, the US manufacturer most closely associated with Liverpool, but who also provide kits for Porto and Sevilla.

As a sign of growing commercial activity, Stoke announced two naming rights deals in July with parcel delivery firm DPD and Novus Property Solutions both sponsoring stands in the stadium.

Wages rose 10% (£6 million) from £61 million to £67 million, leading to the wages to turnover ratio worsening from 62% to 67%. Since 2013, revenue has surged by £33 million (50%) , but Coates has been determined that the higher TV money would not simply pass through to the players (as with previous deals), so the wage bill has only grown by £6 million (10%).

The amount paid to the highest paid director, believed to be chief executive Tony Scholes, rose from £773,000 to £801,000 (including pension contributions).

Although Stoke’s wages to turnover ratio has improved from the 91% peak in 2013, last season’s 67% is likely to be one of the highest in the Premier League in 2015, as only two clubs reported worse ratios in 2014 (WBA and Fulham).

That said, this highlights Stoke’s tricky balancing act, as their £67 million wage bill is one of the lowest in the top flight. In 2013/14 it was only the 16th highest, which shows how much they outperformed by finishing 9th, given that there is normally a very close correlation between wages and success on the pitch.

To place this into context, it is only around a third of the elite clubs, who all pay around £200 million: Manchester United £203 million, Manchester City £194 million, Chelsea £193 million and Arsenal £192 million.

Nevertheless there is a clear bunching of clubs in the £60-70 million range, as the traditional bigger spenders like Newcastle United, West Ham and Aston Villa have only grown a little, while the nouveaux riches like WBA, Swansea City, Southampton and indeed Stoke have all had to significantly increase their wage bill in order to compete.

As Stoke’s 2011 accounts said, “there was a substantial increase in player wage costs, which had been planned for, to enable us to consolidate our position in the Premier League.” The theme was repeated the following year: “The further strengthening of the squad led to a planned, but nevertheless sizeable increase in player wage costs.”

Clearly wages have not been growing at such a dramatic rate in the past couple of years, as can be seen in 2014/15, as Stoke’s £6 million increase has been outpaced by other mid-tier clubs, e.g. Southampton £9 million, West Ham £9 million and Everton £8 million. However, the expectation would be that the next set of accounts in 2015/16 should feature a reasonable rise after the addition of the recent signings.

Stoke’s three-stage strategy since their return to the Premier League is evidenced by their transfer spend. In the initial five years between 2008/09 and 2012/13 they had a net spend of £88 million, as they built a competitive squad, splashing out on the likes of Peter Crouch, Kenwyne Jones, Wilson Palacios and Cameron Jerome.

However, they then slammed on the brakes in the following two seasons, making a number of free transfer signings (Phil Bardsley, Steve Sidwell, Mame Biram Diouf, Stephen Ireland and Marc Muniesa), resulting in net transfer spend of just £5 million.

Although the net spend was only £3 million in 2015, this masks gross spend of £21 million (Shaqiri, Joselu, Philipp Wollscheid and Jakob Haugaard), as this was largely offset by the sales of Begovic, N’Zonzi and Huth.

Nevertheless, Stoke’s net spend of £8 million over the last three seasons is the second smallest in the Premier League, only “beaten” by Tottenham, who have net sales thanks to the Bale deal. Obviously, nobody would expect Stoke to spend at the same level as clubs like Manchester City, Manchester United, Arsenal and Chelsea, but it must be galling for Stoke fans to be outspent by the likes of Crystal Palace £67 million, WBA £48 million and Leicester City £40 million – though it should be recognised that promoted clubs have to spend big when they come to the Premier League.

Either way, Mark Hughes pushed for a loosening of the purse strings this summer: “It's fair to say we have done OK, we're probably the lowest spenders in the Premier League. It's not a huge amount, we've done some good deals and good business. That can't be a strategy moving forward, we will have to invest in the team. That costs money and the Coates family know that as well. If we get to a point where a cheque has to be signed the owners are prepared to do that.”

Although net debt was reduced by £5 million from £38 million to £33 million, this was largely due to cash balances rising £7 million from £19 million to £26 million, as gross debt was actually up £2 million from £57 million to £59 million.

The good news is that this is all owned to Stoke City Holdings Ltd, the company that owns the Britannia Stadium and the Clayton Wood training ground, which is ultimately owned by bet365 (under the control of the Coates family). In other words, Stoke City have no external debt with banks, but the friendliest of “in house” debt to their owners in the form of interest-free loans with no fixed repayment term.

Stoke’s £59 million gross debt is by no means the highest in the Premier League. In fact, there are actually five clubs with debt above £100 million, namely Manchester United £411 million, Arsenal £234 million, Newcastle United £129 million, Liverpool £127 million and Aston Villa £104 million.

The fact that Stoke pay no interest on their loans is a major advantage compared to some of their rivals, e.g. West Ham pay £6 million a year, Southampton £3 million and Sunderland £2 million, but is not uncommon with benefactor owners.

It is worth noting that Stoke also had £4 million of contingent liabilities (dependent on the success of the football club or players making a certain number of club or international appearances). On top of that, there is a further £26 million of transfer fees payable for players purchased after the accounts closed.

Stoke’s improved finances are also reflected in the cash flow statement. Taking 2014/15 as an example, the club generated £9 million from operating activities, before spending £4 million on player registrations and infrastructure. They did require a further £2 million loan from the parent company, but this was a significant reduction on previous years (£15 million in 2014, £18 million in 2013).

Over the years, bet365’s ongoing investment and support has been crucial to the club’s development. Although cash flow from operating activities has been positive, the money required to fund investment in players has only been covered by “the family making huge cash injections every year.” In fact, since bet365 took control in May 2006, the owners have put in around £100 million (£97 million of loans and £2 million of share capital).

Not only have they provided this funding, but they have also written-off £32 million by converting some of the loans to equity and disposing of an investment in a subsidiary in 2010. In fairness, they can probably afford it, as the Sunday Times Rich List revealed that they had become the UK’s first betting billionaires.

It is instructive to review how the club has operated since 2008. In that period, Stoke had available cash of £157 million, which came from two sources: (a) £67 million from operating activities (after paying the ongoing expenses); and (b) £90 million from owners’ loans. Almost 80% of this (£124 million) has gone on player investment, while cash balances increased by £25 million.

All external loans have been repaid (£3 million), while there has only been £4 million of capital expenditure, though this is a little misleading, as most of the club’s infrastructure investment is made via Stoke City (Property) Limited, e.g. £3 million was invested into the Clayton Wood training ground by this company in 2010.

In line with the trend at other clubs, Stoke’s cash increased last year from £20 million to £26 million, though this is still a long way behind the leaders, e.g. Arsenal £228 million, Manchester United £156 million and Manchester City £75 million.

Although Stoke have moved towards self-sufficiency, as we have seen, much of their success has been due to the backing of the Coates family, which is likely to still be required in the future (albeit to a lesser extent), especially if the club wishes to reach the proverbial next level.

"Mr Bojangles"

Unlike some owners, Peter Coates has never looked for a return on his investment: “Me and my family, we don’t look at Stoke as a business. For us it’s something important for the area and something we want to do.” Indeed, the family connection was strengthened in the summer when his son John became vice-chairman.

Their commitment has been reinforced by the £9 million investment in the Academy and training facilities, though Stoke have to date struggled to develop players for the first team, as Coates admitted: “We are desperate to bring young players through. I would like to see half-a-dozen players on the bench who are Academy products. But we are not there yet.”

"Irish heartbeat"

However you look at it, Stoke have made steady progress. In contrast to the rollercoaster ride experienced at similar clubs, they have operated a sensible business model with a mixture of investment and (realistic) ambition to become a fixture in the top half of the Premier League.

It will be difficult for them to go much higher, given the vast wealth of the leading clubs, but it won’t be for the lack of trying. As Hughes said, “I think it’s exciting times for Stoke City, everyone can see there’s more progress to be made and we want to see how far we can take the club.”