The 2014/15 season was not one of the best for Everton, as they slumped to 11th in the Premier League. Not just my assessment, but also that of the club’s hierarchy, as chairman Bill Kenwright drily observed that “last season was not the one Evertonians had hoped for.” Even the normally irrepressible manager Roberto Martinez noted, “2014/15 was a very tough and demanding season at times.”

This was particularly disappointing, as the previous season (Martinez’ first in charge) had seen Everton achieve a club record points haul in the Premier League era, finishing 5th and thus qualifying for the Europa League.

Despite a glut of injuries, Everton have returned to form this season and currently sit 7th in the league, while there is a decent chance of silverware in the Capital One Cup, where they have progressed to the quarter-finals.

"Spanish Steps"

In contrast to the travails on the pitch, chief executive Robert Elstone claimed, “We made great strides off the pitch in 2014/15”, though in truth Everton’s financial figures were a bit of a mixed bag. Yes, the club achieved record turnover of £126 million, but they also made a loss of £4 million, while net debt rose to £31 million.

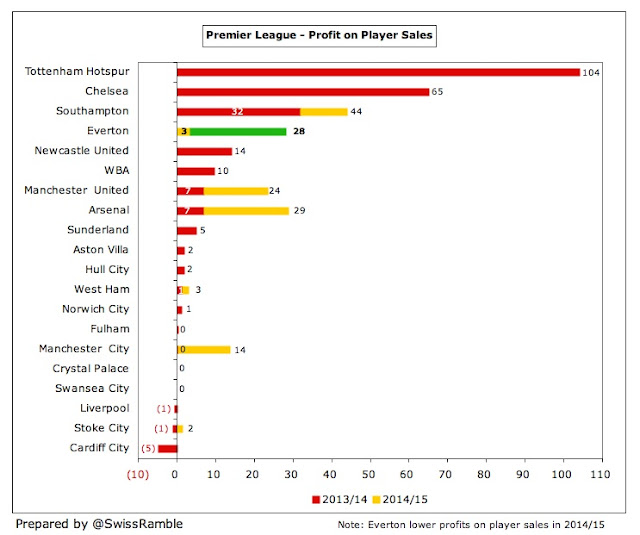

In fact, the bottom line was £32 million worse than the previous year, as Everton moved from a £28 million profit to a £4 million loss. This was largely due to profit from player sales falling by £25 million to just £3 million, as the 2013/14 figures included the sale of Marouane Fellaini to Manchester United.

Revenue rose £5 million (4%), despite broadcasting income falling £3 million (4%) to £82 million, as a result of increases in both commercial income, up £7 million (37%) to £26 million, and gate receipts, £1 million (8%) higher at £18 million. On the other hand, there were substantial increases in the cost base: wages climbed £8 million (12%) to £78 million; other operating costs rose £4 million (16%) to £30 million; and player amortisation was up £1 million (5%) to £20 million.

This was slightly offset by net interest payable, principally from the servicing of securitised debt and bank overdraft, decreasing by £1.3 million (26%) to £3.8 million, due to a reduction in interest rates.

It should be noted that Everton have changed the way that they have classified revenue this year, including a restatement of the 2014 results. This has no net impact, but means that the figures reported for gate receipts and broadcasting income have reduced, while commercial income has increased (by £6.3 million in 2014). The club stated that this now represents a “more accurate presentation of turnover”, though maybe the board just got fed up with all the criticism received about the relatively low level of commercial income.

In fairness to Everton, it is no great surprise that profits have fallen, as this is the second year of the current three-year Premier League deal, so there are limited opportunities for significant revenue growth, while wage bills continue to grow. This can be seen by the fact that four of the seven Premier League clubs that have reported 2014/15 figures to date have announced lower profits.

That said, Everton are one of only two clubs that have actually lost money, the other one being Manchester United, whose £4 million loss is almost entirely due to their failure to qualify for Europe in 2014/15. Given the amount of TV money on offer, the expectation would be that most clubs in the top flight would manage to be in the black. Indeed, 15 of the 20 Premier League clubs were profitable in 2013/14.

Everton had the 4th highest profit in the Premier League that season with £28 million, only behind Tottenham £80 million, Manchester United £41 million and Southampton £29 million.

This shows how much a football club’s profitability can be influenced by profits on player sales. As an example, in 2014/15 Southampton made £44 million from this activity, manly due to the sales of Adam Lallana and Dejan Lovren to Liverpool plus Calum Chambers to Arsenal, while the previous season saw Tottenham Hotspur make an amazing £104 million (largely due to the mega sale of Gareth Bale to Real Madrid) and Chelsea £65 million (David Luiz to Paris Saint-Germain).

Everton themselves made £28 million from player sales in 2013/14, largely due to Fellaini’s transfer, but just £3 million in 2014/15. In terms of keeping their squad together, this is clearly a good thing, but obviously had a big adverse effect on their financial results.

To an extent, Everton’s small loss in 2015 is a return to their customary performance, as they had been consistently loss-making between 2006 and 2012 (with a cumulative £45 million loss in those seven years) before the improvement seen in 2013 and 2014

However, it is fair to say that in many years Everton have effectively subsidised their underlying deficit with the sale of a major player. Indeed, in the 11 years from 2005 Everton basically broke-even (making total profits of £5 million), but £128 million of this came from player sales. This has been a regular theme going back to 2005 when the £24 million profit was almost entirely because of Wayne Rooney’s big money transfer to Manchester United.

Not only that, but Everton have also been selling off the family silver with a number of sale and leaseback deals plus the sale of their Bellefield training ground in 2011, which generated an £8 million profit.

Given the impact that player sales have on the finances of a club like Everton, it is worth exploring how football clubs account for transfers, as it has a major impact on reported profits. The fundamental point is that when a club purchases a player the costs are spread over a few years, but any profit made from selling players is immediately booked to the accounts.

So, when a club buys a player, it does not show the full transfer fee in the accounts in that year, but writes-down the cost (evenly) over the length of the player’s contract. Therefore, if Everton spent £25 million on a new player with a 5-year contract, the annual expense would be only £5 million (£25 million divided by 5 years) in player amortisation (on top of wages).

However, when that player is sold, the club reports straight away the profit on player sales, which essentially equals sales proceeds less any remaining value in the accounts. In our example, if the player were to be sold 3 years later for £32 million, the cash profit would be £7 million (£32 million less £25 million), but the accounting profit would be higher at £22 million, as the club would have already booked £15 million of amortisation (3 years at £5 million).

This is all horribly technical, but it does help explain how clubs can spend big in the transfer market with relatively little immediate impact on their reported profits. Even though the annual cost of purchasing players is therefore somewhat reduced in the profit and loss account, it is worth noting that the impact of Everton’s increasing spend in the transfer market over the last two years has pushed up player amortisation, which has just about doubled from £11 million in 2013 to £20 million in 2015.

Obviously this is nowhere near as much as the really big spenders like Manchester United (£100 million), Chelsea (£72 million) and Manchester City (£70 million), but it is something that Everton will have to keep an eye on in future years.

The other side of the coin here is that all these signings have helped strengthen the balance sheet with player values (reported as intangible assets) climbing to £53 million, compared to only £24 million just three years ago. So what, you might say, but it is obviously good for any club to have better quality “assets” on the pitch.

In point of fact, the accounting treatment understates the value of Everton’s squad, as it does not fully reflect the market value of internationals like John Stones, Seamus Coleman, Phil Jagielka, James McCarthy and Leighton Baines, while attributing no value to homegrown players like Ross Barkley.

Given all the accounting complexities arising from player trading, clubs often looks at EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxation, Depreciation and Amortisation) for a better understanding of how profitable they are from their core business. In Everton’s case, EBITDA was only slightly above zero for many years before shooting up to £25 million in 2014, though it did fall back to £18 million last season.

This highlights the impact of the new TV deal in 2014, as the combined £43 million of EBITDA in the last two seasons is nearly twice as much as the club generated in the previous seven seasons.

This is pretty good, but at the same time helps to outline the challenge for clubs like Everton, as the EBITDA at the leading clubs is significantly higher, despite their larger wage bills: Manchester United £120 million, Manchester City £83 million, Arsenal £64 million, Liverpool £53 million and Chelsea £51 million.

Since 2009 Everton’s revenue has grown by 58% (£46 million) from £80 million to £126 million. Not bad at all, but much of this is down to the increasing TV deal (£33 million), which is thanks to the central Premier League negotiating team, as opposed to the club’s board. Commercial revenue has apparently risen by £17 million in the same period, while gate receipts have fallen £4 million, though this is misleading, as it does not take into consideration the club’s restatement of the revenue categories in 2014.

In any case, the growing TV money has allowed Everton to change their traditional business model, so they no longer need to sell to buy, which in the past led to the departures of players like Jack Rodwell, Mikel Arteta, Joleon Lescott and Andy Johnson.

Despite significant growth over the last two years, Everton’s revenue of £126 million is still a lot lower than the Champions League elite, e.g. the top four clubs all earn well above £300 million: Manchester United £395 million, Manchester City £352 million, Arsenal £329 million and Chelsea £320 million.

Little wonder that Kenwright once asked, “How does Everton do it? How do we consistently perform so well in these days of cheque book fuelled football?” This is a reference to Everton consistently outperforming their revenue level.

That said, Everton are not doing too badly in revenue terms, as they are the 8th highest in the Premier League, just behind Newcastle United, but ahead of Aston Villa, West Ham and Southampton.

In fact, if the gross revenue from the outsourced catering and kit deals were to be added back, then Everton’s revenue would be around £8 million higher at £134 million.

What’s more, Everton’s revenue is now the 20th highest in the world according to the Deloitte Money League, ahead of famous clubs such as Marseille £109 million, AS Roma £107 million and Benfica £105 million.

However, this does not help them much domestically, as there are no fewer than 14 Premier League clubs in the world’s top 30 clubs by revenue (and all of them are in the top 40). As Roberto Martinez emphasised, “The Premier League is the most competitive league in Europe week in week out.”

Everton’s revenue mix shows their reliance on Premier League TV money: broadcasting 65% (though this was down from 70% in 2014), commercial 21% and gate receipts 14%. As Elstone said, “Our financial performance, like so many Premier League clubs, was underpinned by the second year of a TV deal that beat all expectations.”

That’s certainly the case. In fact, in 2013/14 nine Premier League clubs had a greater reliance on TV money than Everton with four clubs getting more than 80% of their revenue from broadcasting: Crystal Palace, Swansea City, Hull City and WBA.

In 2014/15 Everton’s share of the Premier League TV money fell 5% from £85 million to £81 million. The distribution of these funds is based on a fairly equitable methodology with the top club (Chelsea) receiving £99 million, while the bottom club (QPR) got £65 million.

Most of the money is allocated equally to each club, which means 50% of the domestic rights (£22.0 million in 2014/15), 100% of the overseas rights (£27.8 million) and 100% of the commercial revenue (£4.4 million). However, merit payments (25% of domestic rights) are worth £1.2 million per place in the league table and facility fees (25% of domestic rights) depend on how many times each club is broadcast live.

In this way, Everton were hurt by falling from 5th place to 11th, which cost them £7 million, though this was slightly mitigated by being shown live on one more occasion, which was worth an extra £1 million. There was also £4.4 million of commercial revenue awarded to all Premier League clubs, though I suspect that Everton might have reported this within commercial income, even though most other clubs classify it as broadcasting income.

"Heart and Soul"

This would help explain why Everton’s total broadcasting income in the accounts was only £81.7 million, even though the total Premier League distribution was £80.6 million and Europa League prize money was around £5 million (€7.5 million). Incidentally, this would also account for some of the reported growth in commercial income.

Either way, Elstone is right to draw attention to the new TV deal stating in 2016/17: “Of course, we are now less than a year away from receiving the benefit of the next deal and one that makes the current, outstanding deal look modest.”

My estimates suggest that Everton would receive an additional £37 million under the new contract, increasing the total received to an incredible £118 million. This is based on the contracted 70% increase in the domestic deal and an assumed 30% increase in the overseas deals (though this might be a bit conservative, given some of the deals announced to date). Of course, if they were to finish higher in the league table, they would earn even more.

Everton’s Europa League experience saw them earn €7.5 million. This was not much reward for their efforts in reaching the last 16, which included wins against Wolfsburg, Lille and Young Boys Bern, but was at least the highest sum received by the English entrants in that tournament.

Martinez has claimed that “being a regular team in Europe is what we want”, but also struck a note of caution when adding that it “unquestionably affects performance in the Premier League”, as it tests squad strength to the limit.

The big money is obviously in the Champions League with English clubs averaging €39 million in 2014/15 and is getting higher, as the new TV deal from the 2015/16 season is worth an additional 40-50%, thanks to BT Sports paying more than Sky/ITV for live games.

Everton’s gate receipts grew by £1.1 million (7%) from £16.8 million to £17.9 million in 2014/15 through a combination of higher attendances and more match day income from participation in the Europa League, offset by fewer home domestic cup games. Attendances rose from 37,732 to 38,406, the highest recorded since the 2003/04 season with 12 of 19 Premier League games sold out.

The club attributed the increase in attendances to “successful season ticket and hospitality membership campaigns” with almost 28,000 season ticket holders being 4,000 more than the previous season.

Although there were some small increases in ticket prices in 2014/15, these were frozen for the 2015/16 campaign. The club has emphasised its “commitment to affordable pricing and making football at Goodison accessible to young fans” with the continuation of the £95 season ticket for junior school children.

Despite all these encouraging initiatives, the fact remains that Everton’s match day income of £18 million is miles behind the top six clubs: Arsenal £100 million, Manchester United £91 million, Chelsea £71 million, Liverpool £51 million, Tottenham £44 million and Manchester City £43 million.

This was acknowledged by Elstone, “The real springboard to greater things will be the new stadium”, and the club remains in talks with Liverpool City Council over Walton Hall Park. However, Everton fans would be entitled to be sceptical about this project, as two other proposed stadium moves have come to nothing: first King’s Dock in 2003, then Kirkby in 2009.

Most obviously, there is the question of who would pay for a new stadium? Elstone has already said, “We would need to think very carefully about a new stadium that adds the burden of significant debt on the club.” The hope would be that Liverpool City council would put in “a level of investment” as part of a wider regeneration of the area, but this appears a tad optimistic given the spending cuts imposed on the council. Either way, it is clear that little tangible progress has been made with Elstone informing this week's AGM that no agreement had been reached on any partnership.

In that meeting, the chief executive once again spoke of the “fantastic opportunity for the football club”, but described it as “a hugely challenging funding project”. He has been seeking a potential naming rights partner, but these are difficult to secure, and he admitted earlier this year that this is proving slower than anticipated.

Although Kenwright has admitted that “leaving our beloved Goodison Park would bring a degree of sadness”, the need for a new stadium is now more important than ever with West Ham about to benefit from their move to the Olympic Stadium, while Tottenham and Chelsea have both announced major redevelopment initiatives.

Everton’s commercial income surged 37% (£7 million) from £19 million to £26 million in 2014/15, comprising £10.4 million for sponsorship, advertising and merchandising plus £15.6 million for other commercial activities. The sponsorship growth was due to “the long-term support of key partners such as Chang and Kitbag, as well as the club’s first year of the new kit partner deal with Umbro”, while other commercial revenue benefited from participation in the Europa League.

As we saw earlier, it is not completely clear what the club has included within commercial income. For example, if we add up the money from the three major deals (Chang £5.3 million, Umbro £6 million and Kitbag £3 million), we get £14.3 million, which is more than the total of £10.4 million reported for sponsorship, advertising and merchandising.

Whatever it consists of, Everton’s commercial income of £26 million pales into insignificance compared to heavyweights such as Manchester United, who generate £196 million from this activity. That comparison might be a little unfair, but it is worth noting that Tottenham earned £42 million and Aston Villa and Newcastle United also earned £26 million (in the 2013/14 season).

"All roads lead to Rom"

That said, the comparisons are a bit misleading, as Everton have outsourced their catering and kit deals. If they were to report these revenues gross (like most other clubs), their commercial income would rise by £8 million to £34 million.

This is not too shabby, but could be better, as Elstone admitted: “Our commercial revenues benchmark well against teams finishing below sixth in the table, but it is a fact that we lag well behind – and disproportionately behind – clubs playing regularly in Europe.”

Many supporters have criticised the 10-year Kitbag deal, which provides a guaranteed £3 million a year plus royalties for running the retail operation, replacing a deal with JJB worth £1.6 million a year. However, Elstone seems happy enough, "Kitbag is a great deal for this football club. It was from day one." He has also described it as a good arrangement that “de-risks Everton in a notoriously difficult business sector”.

However, it does betray a lack of ambition, especially when we look at some of the kit supplier deals secured by other clubs, e.g. Arsenal – Puma £30 million, Liverpool – New Balance £28 million, Tottenham – Under Armour £10 million, and Aston Villa – Macron £4 million.

Similarly, while it is laudable that Everton have the longest running shirt sponsorship deal in the Premier League, having first signed with Chang back in 2004, this does raise the question of whether they could get more elsewhere than the £5.3 million from the current deal (worth £16 million for the three years up to 2016/17).

The Umbro deal was described as a club record and is reportedly worth £6 million a season, which would be twice as much as the previous Nike contract, though the latest accounts suggest that it might not be so high in reality.

Everton’s wage bill rose 12% (£8 million) to £78 million, following continued investment in the squad, with the additions of Romelu Lukaku, Gareth Barry, Muhamed Besic and Brendan Galloway, together with loan spells for Christian Atsu and Aaron Lennon. In addition, new contracts were awarded to Roberto Martinez, Ross Barkley, Seamus Coleman and John Stones.

Furthermore, the average number of employees increased from 247 to 274, including unexplained growth in management and administration from 57 to 71.

The wages growth outpaced revenue growth, so increased the wages to turnover ratio from 58% to 62%. However, this is still the second best ratio the club has recorded in the last six years and is well within the norm in the Premier League with 13 of the 20 clubs grouped in a fairly narrow range of 56-64% the previous season. Furthermore, the ratio would fall to 58% if the club added back its outsourced revenue (retail and catering).

Everton’s ability to outperform their financial resources is underlined by their relatively low wage bill, which was only the 10th highest in the Premier League in 2013/14, behind Sunderland and Aston Villa. Even though this has increased to £78 million, to place this into context, it is dwarfed by the elite clubs, who all pay around £200 million: Manchester United £203 million, Manchester City £194 million, Chelsea £193 million and Arsenal £192 million.

Everton’s 2014/15 increase of £8 million is very similar to the growth reported by other clubs so far: West Ham £9 million, Southampton £9 million and Stoke City £6 million.

One thing that is quite striking in Everton’s accounts is the £4 million growth in other operating costs from £26 million to £30 million, especially as this cost category has shot up by 40% (£9 million) in the last two years without any substantial explanation.

This seems quite high for a club of Everton’s size, especially as the retail and catering businesses have been outsourced, so theoretically other operating costs should be lower than other clubs (as net profits are reported in revenue).

Even though Kenwright has argued, “We’re not a selling club. Never really have been.”, Everton averaged net sales of £7 million a year between 2009 and 2014. However, that has changed in the last two years with average net spend of £26 million, as the club has made no major sales, but invested significant sums on improving Martinez’ squad, smashing their own transfer record in the process when bringing in Lukaku from Chelsea.

Elstone accepted that things had changed: “In the past, when 85p in every £1 we earned was spent at Finch Farm, we had little scope to strengthen the club away from the training ground.”

He underlined the move away from the previous hand-to-mouth existence: “Increasingly, we’ve also been able to sign talented young footballers, who join us not as the finished article, but as great prospects and yet still command significant transfer fees. Players like Galloway, Henen and Holgate might not have joined with that singular focus on the first team.”

In fact, Everton’s net spend of £51 million in the last two seasons is the sixth highest in the Premier League. Although this was still a long way below the two Manchester clubs (City £151 million and United £145 million), it was surprisingly more than Chelsea £40 million and only juts behind Liverpool £57 million.

Clearly, fans will be concerned that Everton will be tempted to sell their young stars with Chelsea offering £40 million for John Stones in the summer and Lukaku and Barkley also worth large sums in today’s market.

However, Martinez says that Everton are no longer forced to sell their prize assets: “We don't fear that situation. What you fear is when you have to sell players to balance the books, when the owner says you need to cash in on two or three star players, that becomes a problem. But it is not the situation at Everton. That is not to say we are going to sell any player or not sell any player, but the decisions we make will be for the benefit of the squad and club going forward.”

Everton’s net debt rose £3 million from £28 million to £31 million, but the gross debt was actually cut by £9 million from £49 million to £40 million with the real driver being the £12 million reduction in cash balances, which fell from £21 million to £9 million. Thanks to higher TV money, not to mention the funds from the Fellaini sale, net debt has improved considerably from the £45 million level in the years up to 2013, which Elstone explained thus: “our pursuit of success has stretched our finances.”

There are basically two elements to Everton’s debt: (a) 25-year loan of £21 million, which bears a high interest rate of 7.79%, leading to annual payments of £2.8 million; (b) an annual loan of £19 million renewable every August, securitised on Premier League TV money, at a stonking 8.2% interest rate.

The short-term loan was taken out with Vibrac, a shadowy offshore corporation based in the British Virgin Islands, which has also provided funding to other English clubs, including West Ham, Southampton, Fulham and Reading. This loan was repaid in August, but has been replaced by another loan with the equally mysterious James Grant (JG) Funding.

Everton also have contingent liabilities of £20 million (£9 million dependent on future appearances and £11 million loyalty bonuses if certain players are still with the club on specific dates), up from £13 million the previous season. On top of that, the club confirmed that it has entered into net transfer agreements since the accounts closed of £22 million.

Like many other clubs, it is clear that Everton are spending as much as they can, thus building up their transfer debt, in order to give themselves the best chance of success, though this should not be a problem, so long as they avoid the nightmare scenario of relegation.

In fairness, Everton’s debt is one of the lowest in the Premier League with only seven clubs owing less than the Toffees. In fact, five clubs have debt above £100 million, namely Manchester United £411 million, Arsenal £234 million, Newcastle United £129 million, Liverpool £127 million and Aston Villa £104 million.

The high interest rate on Everton’s loans mean that their financing costs are among the largest in the Premier League. Although nowhere near as much as the interest paid by the likes of Manchester United and Arsenal, this certainly does not help the club’s finances. Looked at another way, the £4-5 million paid out each year in interest would fund the wages of one world class player (or two very good additions to the squad).

The significance of interest payments is highlighted by looking at the 2015 cash flow. Cash generated from operating activities was £11m, but the cash balance ended up falling £12 million after a series of payments: £7 million net on player transfers; £4 million on those interest payments; £3 million on capital expenditure (stadium refurbishment and a new pitch); and £9 million repayment of loans.

This unwelcome burden is even more emphasised when reviewing the cash flow over the last seven years. In that period, Everton generated £61 million of cash, mainly from operating activities £49 million, though this was supplemented by the sale of the old training ground £9 million and other loans (net) £3 million.

Nearly half (46%) of this cash £28 million was required for interest payments, which was more than the £25 million spent on “good” things: £17 million for new players and £8 million infrastructure investment. The remaining £8 million simply increased the cash balance.

Of those clubs that have so far published their 2015 accounts, Everton and Southampton are the only ones to have reduced cash balances. Others have significantly increased cash, notably the “big boys”, i.e. Arsenal (up to £228 million), Manchester United £156 million and Manchester City £75 million.

Of course, those hefty interest payments to external finance organisations underline the fact that the current Everton directors have not invested in their club, in stark contrast to benefactors at other clubs, who have put in substantial sums without taking a penny of interest. This helps explain why some supporters are unhappy with the board, as seen by a hired plane flying over the match against Southampton in August trailing the banner “Kenwright & Co #timetogo”.

The club claim that they are open to a sale, but it has not gone unnoticed that they have been looking for a buyer for a long time. Back in 2012 Kenwright proclaimed, “My desire to find a person, or institution, with the finance to move us forward has not diminished. We will find major investment.”

"Born to run"

However, since then, nothing, nada, zilch. There were whispers of American interest recently, but one of the potential buyers, Rob Heineman, admitted that his Sporting Club group were never close to a takeover.

This has led some to believe that Everton are not entirely serious in their quest for investment, though to be fair other clubs such as Aston Villa and West Brom have also struggled to find a suitable purchaser in the last few years.

Elstone has maintained the party line: “The search for the funds that will allow the club to leap forward continues without any slowing down or any less enthusiasm. It is worth stating again, and very clearly, there are no unreasonable conditions on the sale of Everton. The only condition is one we think is perfectly reasonable - that the new owner has to want to, and must be able to, take the club forward.”

Fair enough, but if a club like Everton with the 8th highest revenue in the Premier League, relatively low debt, a mega new TV deal on the horizon, opportunities for commercial growth and a much-admired academy, cannot find a buyer, then something is surely amiss.

"Call me"

It’s not so much that Kenwright and Elstone have done anything wrong, it’s the fact that they appear to be relatively comfortable with the status quo, not showing the requisite ambition to drive the club forward.

The club’s Latin motto, “Nil Satis Nisi Optimum” (“Nothing but the best is good enough”), may feel a touch ambitious when competing against the riches of today’s elite, but as Martinez rightly said, Everton should “strive to be the best we can be.”

The manager added, “We want to build around young players – our strategy is to build something and keep what we see as the future. We want to achieve things and see how high we can go.” Spot on, Roberto.

0 comments:

Post a Comment