There seems to be no end to the misery that Aston Villa put their supporters through. The famous Midlands club, one of a select few to have won the European Cup, is stuck at the bottom of the Premier League table and look destined for a seemingly inevitable relegation, which would be the first time they had dropped from the top flight since 1987.

Manager Rémi Garde described securing safety as “an impossible mission that we have to make possible”, though it would not be a major shock if the Frenchman were to be given his marching orders any time soon, given their impotent form. In truth, it always seemed a strange decision to entrust Villa's fate to a man with no management experience in the Premier League.

Villa’s plight should not be overly surprising since they have struggled to avoid relegation in the last four seasons, culminating in finishing 17th in 2014/15, the club’s worst performance since the creation of the Premier League in 1992. Hopes of a better season had previously flickered during Villa’s run to the FA Cup Final, but a harsh dose of reality was administered by Arsenal during a 4-0 defeat at Wembley.

"I've been driving in my car, it's better than a Jaguar"

It seems like ages ago that Martin O’Neill guided Villa to three successive sixth places between 2008 and 2010, though crucially he failed to break into the lucrative Champions League. Since those heady days, Villa have staggered from one crisis to another, not helped by significant managerial upheaval, as noted by new chairman Steve Hollis, “five different managers in five seasons.”

Gérard Houllier lasted less than a year due to health problems, and was replaced by Alex McLeish, unbelievably brought in from bitter rivals Birmingham City. Paul Lambert managed to survive for nearly three years, but his uninspiring brand of football eventually led to his dismissal. Then came the arrival of “tactics” Tim Sherwood, who did at least manage to save Villa from relegation, but his eight-month reign ended on a sour note with six consecutive losses.

This was particularly unimpressive, as the club had splashed out more than £50 million on new players in the summer, though it’s fair to say that the recruitment campaign has been utterly calamitous.

"Do you believe in the Westwood?"

Much of the blame for Villa’s woes has been laid at the feet of owner Randy Lerner. Fundamentally, the American appears to be a good man, pumping vast sums of money into the club, but he seemingly has little idea how to run a football club.

His strategy has swung from one extreme to another since he bought the club in September 2006. Initially, he poured in money to support O’Neill’s hefty spending, though this resulted in an unsustainable wage bill. Then, he engaged reverse gear, turning off the financial taps and looking to cut the wage bill with a focus on youth development. This was no more successful, so he is now once again pushing the boat out; only he’s doing it very badly.

Lerner’s reputation has not been helped by his lack of visibility at the club. He has effectively acted like an absentee landlord, letting his house fall into disrepair. Worse, he has chosen appallingly when hiring people to run the club for him.

As he recently admitted, “That Aston Villa can and should operate in a far more stable and on a far more successful level, both in terms of football as well as commercially, is plainly clear. It is similarly clear that this great club has not been on a stable footing for at least five years.”

"Idrissa Gueye, it shouldn't ever have to end this way"

His latest move to stop the downward spiral is to bring in Steve Hollis as chairman. The former Midlands chairman of financial services firm KPMG, Hollis has wasted little time in cleaning house with chief executive Tom Fox and sporting director Hendrik Almstadt both exiting stage left.

The not-so-fantastic Mr. Fox was a good speaker, albeit often employing tiresome business clichés while frequently promising “jam tomorrow”, but his period in charge can only be considered as dreadful. As Hollis wryly observed when describing Villa’s performance, “You can’t say it’s gone right.”

The board has been strengthened with the appointments of David Bernstein, former chairman of the Football Association and Manchester City, and Mervyn King, the old governor of the Bank of England, plus ex-Villa manager (and forward) Brian Little as an advisor. Hollis was maybe stretching a bit when he described these additions as “football gurus”, but they could hardly do worse than their less than illustrious predecessors.

Villa’s results off the pitch have been every bit as terrible as those achieved on the pitch, as seen in the 2014/15 figures. The loss before tax shot up from £4 million to £28 million, primarily due to the wage bill increasing by £14 million (21%) to £84 million and another £3 million termination payment following a change in manager, this time Paul Lambert.

Other expenses were £2 million higher, while player amortisation rose £1 million to £20 million. Profit on player sales dropped £1 million to just £375,000.

Revenue fell slightly by £1.2 million to £116 million, mainly due to a £3.2 million reduction in player loans from £5.7 million to £3.2 million and a £1.3 million decrease in broadcasting revenue to £71 million, as the extra FA Cup money was more than offset by the smaller Premier League distribution following a lower league place.

This was partly compensated by commercial income rising by £2.2 million (9%) to £27.9 million and gate receipts increasing by £1million (8%) to £13.8 million, due to more home games from the cup run.

Villa’s £28 million loss is the largest reported to date in the Premier League for 2014/15, just ahead of Chelsea’s £23 million. So what, you might say, don’t all football clubs lose money?

Not any more. Although football clubs have traditionally made losses, the increasing TV deals allied with Financial Fair Play (FFP) mean that the Premier League these days is a largely profitable environment. In fact, ten clubs have so far reported profits in 2014/15 with just four clubs losing money and two of those (Manchester United and Everton) only lost £4 million.

In stark contrast to Villa, their Midlands neighbours Leicester City registered a £26 million profit, while even Stoke City made £6 million. It really is some kind of a special “achievement” for Villa to lose so much money in today’s Premier League.

One obvious reason is Villa’s inability to make money from player sales, as their profit of £0.4 million was one of the lowest in the Premier League. To place that into context, Liverpool’s profit from this activity last season was £56 million, while Southampton made £44 million.

Of course, this is somewhat of a double-edged sword, as the lack of profitable player sales might be considered as a sign that the club has done well to keep its squad together, but it could also be that they have no players that other clubs would like to buy.

Villa have reported nine successive years of losses in Lerner’s tenure. Since he bought the club, it has accumulated losses before tax of £249 million – near as damn a quarter of a billion pounds, averaging £28 million a year. That’s an awful lot of money to throw at a club that is almost certain to be relegated.

Last year saw a false dawn when the loss was only £4 million. Indeed, Robin Russell, the CFO, announced, “We are very pleased to be able to report improved results after a period of heavy financial losses.” The club added, “By controlling costs, we have been able to take advantage of the new Premier League broadcasting deal to bring the club closer to self-sufficiency”, which has proved to be as reliable a forecast as Michael Fish advising that there wouldn’t be a hurricane in 1987.

The next best result since 2009 was the £18 million loss in 2011/12, but this was boosted by £20 million of exceptional items and £27 million profits from player sales, so the underlying figures were just as abysmal as the previous years.

The £20 million exceptional item refers to the once-off waiver of interest on loans provided by Lerner. Although the club had been booking around £6 million of interest payable under the terms of the loan agreement, he never actually took a cash payment, another example of the owner’s generosity.

On the other hand, Villa have also booked £30 million of exceptional costs since 2011, including £12 million in 2012 alone. These could justifiably be described as the costs of mis-management, as these include termination payments made to sacked coaching staff and the accounting cost of reducing the value of poor player purchases. Of course, next year’s accounts will again include such a payment, this time to Sherwood (and possibly also Garde).

This is part of the price that the club has paid for constantly changing manager, though this has also influenced player spend, as each incoming manager wants to recruit his own players, while getting rid of many of those accumulated by the previous regime.

That said, hardly any money has been made from player sales in the last three seasons. Villa have earned less than £2 million in this period, including a small loss in 2013.

Before then, this activity had been quite profitable for Villa, earning them £79 million in the five years up to 2012. The 2011/12 season alone brought in £27 million profit on player sales, largely due to the big money moves of Stewart Downing to Liverpool for £20 million and Ashley Young to Manchester United for £17 million.

Last year Lerner noted the importance of player sales to the mid-tier: “For clubs like Southampton and Swansea, their ability to sell players at premium prices wisely has been, to my mind, a key part of their ascent and their increasingly established position in the top half.

It was therefore no great surprise that Villa made some big sales last summer, notably Christian Benteke to Liverpool and Fabian Delph to Manchester City. According to a note in the accounts, this will deliver £40.5 million of net income “taking into account the applicable levies and sell-on clauses”, a reference to the 15% of profit that Villa had to pay Genk, Benteke’s previous club. These deals could be enough to turn Villa profitable in this season’s accounts.

Given that it can have such a major impact on reported profits, it is worth exploring how football clubs account for transfers. The fundamental point is that when a club purchases a player the costs are spread over a few years, but any profit made from selling players is immediately booked to the accounts.

So, when a club buys a player, it does not show the full transfer fee in the accounts in that year, but writes-down the cost (evenly) over the length of the player’s contract. To illustrate how this works, if Villa paid £15 million for a new player with a five-year contract, the annual expense would only be £3 million (£15 million divided by 5 years) in player amortisation (on top of wages).

However, when that player is sold, the club reports the profit as sales proceeds less any remaining value in the accounts. In our example, if the player were to be sold three years later for £18 million, the cash profit would be £3 million (£18 million less £15 million), but the accounting profit would be much higher at £12 million, as the club would have already booked £9 million of amortisation (3 years at £3 million).

Notwithstanding the accounting treatment, basically the more that a club spends on buying players, the higher its player amortisation. Thus, Villa’s player amortisation fell from a peak of £32 million in 2011 to £18 million in 2014, reflecting the slowdown in activity in the transfer market, before rebounding slightly to £20 million in 2015. It should be even higher next year, as this figure does not reflect last summer’s spending spree.

Despite the 2015 increase, Villa’s player amortisation of £20 million is still relatively low. Of course, it is way behind the really big spenders like Manchester United, whose massive outlay under Moyes and van Gaal has driven their annual expense up to £100 million, Manchester City £70 million and Chelsea £69 million, but it is also lower than the likes of Southampton £30 million and Sunderland £27 million.

The other side of the player trading coin is player values, which have been steadily falling. In fact, the 2015 “assets” of £31 million are less than half the £68 million high in 2010, though this figure will rise significantly next year.

As a result of all this accounting fancy footwork, clubs often look at EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Depreciation and Amortisation) for a better idea of underlying profitability. Indeed, Hollis obliquely referenced this, “When you look at the financials of a football club, the big part of the loss comes through the depreciation of the players. It’s a big difference between the reported loss and the cash leakage. In cash terms the club is in a strong position.”

However, the figures don’t really back up the new chairman, as Villa’s EBITDA (cash profit) fell from £19 million to just £1 million in 2015. Admittedly, this is still better than the many negative previous years, but it is really nothing to shout about.

In fact, Villa’s EBITDA is the lowest of all the Premier League clubs that have so far reported in 2014/15. To place it into perspective, Manchester United’s EBITDA is a mighty £120 million, as an example of a club that is in a genuinely strong cash position. Only one other Premier League club has not generated double-digit EBITDA, namely Swansea City.

Villa’s revenue has grown by £35 million (44%) since 2012, almost entirely down to the centrally negotiated Premier League TV deal, with broadcasting increasing by £28 million (64%) in this period. Commercial has only grown by £4 million (16%) in the last three years, even though it has been an area of specific focus, as Fox noted, “the plan is to maximise the revenue potential of the Aston Villa football club brand on a global basis.”

The impression of a club running to stand still was even more starkly illustrated between 2009 and 2013 when there was zero revenue growth. Revenue had risen from £84 million in 2009 to £92 million in 2011, but there was a reduction in revenue in 2012, largely thanks to worse performance on the pitch (dropping from 9th to 16th place in the Premier League and early exits from the cup competitions).

It should be noted that Villa changed the way they split their revenue among the various streams in 2013, so they restated the 2012 comparative, but not prior years. This means that the apparent reduction in match day income and consequent increase in commercial income since 2011 is misleading.

The lack of revenue growth is important, giving the lie to another Fox pearler: “I look at Villa and see a club that should be seventh, eighth or ninth in the Premier League on a perennial basis.” That may be, but their revenue of £116 million is now only the 10th highest in the top tier, behind Newcastle United £129 million, Everton £126 million and West Ham £121 million.

On the one hand, Villa will obviously struggle to compete at the highest level, as there is a financial chasm between them and the top six clubs: Manchester United £395 million, Manchester City £352 million, Arsenal £329 million, Chelsea £314 million, Liverpool £298 million and Tottenham £196 million. On the other hand, Villa earn more than clubs like Southampton, Swansea City, Leicester City and Stoke City, so really should be performing better than them.

In fact, Villa have the 23rd highest revenue in world football, according to the Deloitte Money League, generating more revenue than famous clubs like (deep breath) Napoli, Valencia, Seville, Hamburg, Stuttgart, Lazio, Fiorentina, Marseille, Lyon, Ajax, PSV Eindhoven, Porto, Benfica and Celtic.

That’s obviously a fine accomplishment, but it does not really help Villa domestically, as no fewer than 17 Premier League clubs feature in the top 30 clubs worldwide by revenue.

Note that the Deloitte Money League excludes revenue from player loans, so they have reduced Villa’s revenue of £115.7 million by £2.5 million to £113.2 million in their classification.

Despite the reduction in broadcasting revenue in 2015, this still accounts for 63% of total revenue (excluding player loans). Commercial income has increased from 23% to 25%, while match day is unchanged at 12%.

Villa’s share of the Premier League television money fell by £4 million from £73 million to £69 million in 2014/15, partly due to smaller merit payments for finishing two places lower in the league, and partly due to only being shown live on TV 11 times (compared to 16 the previous season), which reduced the facility fee.

Even though the Premier League deal is the most equitable in Europe with all other elements distributed equally (the remaining 50% of the domestic deal, 100% of the overseas deals and central commercial revenue), this highlights the impact of Villa’s slump on their revenue.

For example, if Villa had maintained their run of 6th place finishes in the five seasons since 2009/10, they would have pocketed an additional £66 million. This highlights the tricky balance between sustainable spending and investing for success. Spending money is obviously not a guarantee, but a safety first approach can end up leaving money on the table.

Of course, there will be a substantial increase from the mega Premier League TV deal starting in 2016/17. My estimates suggest that Villa’s 17th place would be worth an additional £30 million under the new contract, taking their annual payment up to an incredible £99 million. This is based on the contracted 70% increase in the domestic deal and an assumed 30% increase in the overseas deals (though this might be a bit conservative, given some of the deals announced to date).

This is why relegation would be such a big deal for Villa – described by the club as its “key risk”. If they were to drop down, they would get around £38 million in the Championship, including a £35 million parachute payment and £2 million distribution from the Football League, compared to the estimated £99 million in the Premier League, i.e. a £61 million difference.

Obviously, this would be considerably higher than those Championship clubs without parachute payments, who receive only £5 million, leading Hollis to say, “We would have one of the strongest balance sheets in the Championship”

That said, it’s still a considerable reduction in revenue that would require major cuts in the cost base. Hollis confirmed that the club would “be able to take the measures needed to address the drop in income”, not least because the players’ contracts include significant relegation clauses, but they would likely still have to sell the club’s better players.

Another point worth noting is that from 2016/17 clubs will only receive parachute payments for three seasons after relegation, although the amounts will be higher. My estimate is £75 million, based on the percentages advised by the Premier League (year 1 – £35 million, year 2 – £28 million and year 3 – £11 million). Up to now, these have been worth £65 million over four years: year 1 – £25 million, year 2 – £20 million and £10 million in each of years 3 and 4.

Gate receipts climbed by 8% (£1 million) from £12.8 million to £13.8 million in 2014/15, thanks mainly to the FA cup run which included four home ties. This is still only 12th highest in the Premier League, just behind Sunderland, and significantly lower than the elite clubs, e.g. Arsenal earn £100 million from match day income (or eight times as much as Villa).

This is partly due to Villa’s ticket prices being among the lowest in the top flight, even after an average 3% increase in 2014/15. Prices are unchanged this season, with Fox explaining, “We have decided to freeze season ticket prices, as we know it has been a challenging period”, which is one way of putting it.

Villa’s average league attendance of 34,133 was the 11th highest in the Premier League, which is an impressive achievement considering their problems on the pitch, but it is nearly 2,000 lower than the previous season and only 80% of the 43,000 capacity at Villa Park.

Villa’s attendance has steadily declined from the 40,000 peak in 2007/08 to around 34,000, representing a 15% fall and 6,000 fewer fans (or customers), which has clearly hurt the club’s finances. Incredibly, the fans showed their support with attendances actually rising in the previous two seasons, but they would appear to have had enough now.

Commercial revenue rose by 9% (£2.2 million) from £25.7 million to £27.9 million, comprising £10.9 million sponsorship and £17.0 commercial income. That means that commercial revenue has increased by £5 million (22%) in the last two seasons, which is reasonably encouraging.

In fact, this is effectively “the best of the rest”, being better than all Premier League clubs with the exception of the top six, who are miles ahead. For example, Manchester United’s commercial revenue is just shy of £200 million, almost exactly seven times as much as Villa, followed by Manchester City £173 million, Liverpool £116 million, Chelsea £108 million, Arsenal £103 million and Tottenham £59 million.

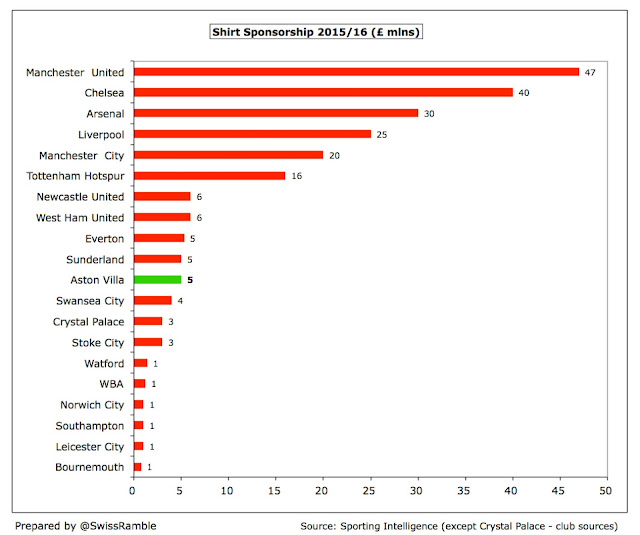

The disparity is most evident when comparing the shirt sponsorship deals. Villa have a two-year deal with Intuit QuickBooks, an accounting software for small businesses, worth £5 million a year that started in the 2015/16 season. This replaced a similar sized deal with Dafabet (though is lower than the previous £8m Genting agreement).

This looks very low compared to the major clubs, who continue to increase their deals, e.g. Manchester United £47 million with Chevrolet and Chelsea £40 million with Yokohama Rubber.

It’s a similar story with Villa’s kit supplier. The current four-year deal with Macron is worth £15 million (£3.75 million a year), running until the end of the 2015/16 season, when it will be replaced by Under Armour. The new contract is reportedly worth more, though it is understood to include significant financial reductions in the event of relegation.

"End of the road I'm traveling, I will see Jordan beckoning"

That’s not too bad, but it pales into significance next to match Manchester United’s “largest kit manufacture sponsorship deal in sport” with Adidas, which is worth £750 million over 10 years or an average of £75 million a year from the 2015/16 season.

In fairness, most clubs outside the absolute elite have struggled to secure such massive deals and Villa would have to enjoy a sustained run of success to substantially improve their commercial deals – though Fox reckoned that Villa could increase this revenue stream by £8-10 million a year.

Amazingly, given their rotten displays, Villa’s wage bill rocketed up by 21% (£14.4 million) from £69.3 million to £83.8 million, not just due to new signings, but new contracts for some players and Paul Lambert.

In addition, there has been a steep rise in headcount. Players, football management and coaches rose from 173 to 185, but there was an even bigger increase in commercial, merchandising and ops from 232 to 261. There’s not exactly been a great return on investment from that yet.

After three years of keeping the lid on this expense by “rationalising the playing squad” and exercising “tight control of players’ wages”, there has been a total change in policy. In fact, this is the record high for Villa’s wages, just above the previous peak in 2011. God knows what the wage bill will be after this summer’s influx of new players.

This increased Villa’s wages to turnover ratio from 59% to 72%. Although this is nowhere near as bad as the 91% in 2011, it’s still the second highest (worst) in the Premier League, only “beaten” by West Brom’s 75%. As a contrast, high-flying Leicester’s ratio is 55%.

Villa’s wage bill is the 7th highest in the Premier League, once again far below the usual suspects: Chelsea £216 million, Manchester United £203 million, Manchester City £194 million, Arsenal £192 million, Liverpool £166 million and Tottenham £100 million (2013/14). However, they are ahead of the others, so are spectacularly punching below their weight.

The wage bills of the mid-term clubs seem to be converging around the £70 million level, e.g. West Ham £73 million, Southampton £72 million, Swansea £71 million, Stoke City £67 million, so Villa have not really made the best use of their extra funds.

It has also not gone unnoticed that the remuneration of the highest paid director has exploded from £266k to £1.25 million, marking the change in chief executive from Paul Faulkner to Tom Fox. Given that Fox was hired in August 2014 and only formerly appointed as a director in November 2014, his annual salary was presumably even higher, as the accounts ran until 31 May 2015, which is frankly almost unbelievable. How's that for a "false narrative", Tom?

Even though there was a slowdown following the excesses of the Martin O’Neill era, it is not true that Lerner stopped spending in the transfer market. In fact, his average annual gross spend over the last five years of £25 million is not much different from the £30 million average in the preceding five years.

This season’s net spend of £7 million masks gross spend of £53 million, as the club brought in Idrissa Gueye (£9 million), Jordan Amavi (£9 million), Jordan Ayew (£8.5 million), Rudy Gestede (£7 million), Jordan Veretout (£7 million), Adama Traore (£7 million), Scott Sinclair (£2.5 million), Joleon Lescott (£2 million) and Micah Richards (free transfer). That’s a lengthy shopping list, but the focus seems to be more on quantity, rather than quality.

As Sherwood explained, “We have sold a lot of players and we brought in a lot of money. The owner has not put that back in his pocket, he has reinvested it in the squad.”

Unfortunately, Villa did not manage to make a signing in the January transfer window, but it must have been difficult to attract talent with the threat of relegation (and lower wages) looming. Moreover, you could not have blamed the club for not throwing good money after bad, as maybe implied by Hollis: “You have got to look at the facts – this club spent £60 million in the summer. That’s a lot of money.”

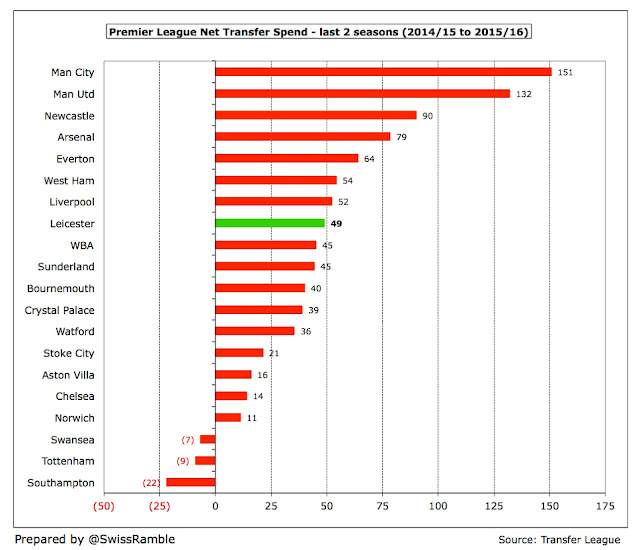

That said, Villa’s recent net spend still lags behind other clubs, e.g. only four Premier League clubs had a lower net outlay than their £33 million over the last three seasons: Stoke City, Southampton, Swansea City and Tottenham (due to Gareth Bale’s huge sale to Real Madrid).

In one piece of good news, Villa’s gross debt has been further cut from £104 million to £31 million, mainly due to Lerner converting £85 million of loan notes into share capital. This followed a similar debt conversion to equity of £90 million the previous year. As a result, Villa’s debt has come down from a peak of £190 million in 2013.

Gross debt now comprises bank loans and overdraft of £20.4 million and owner debt of just £10.4 million. The bank loan charges interest on margins above the Bank of England base rate, while Lerner’s loans are unsecured and interest-free.

In addition to the financial debt, the net cost of the summer transfers after these accounts closed is given as £57 million.

Potential additional transfer fee payments (based on contractual conditions such as number of appearances and retention of Premier League status) remain around the £4 million level, though there are now also contingent liabilities of £3.3 million payable upon the change of ownership of the football club.

Villa’s debt of £31 million is now one of the smallest in the Premier League, much less than Manchester United, who still have £444 million of borrowings even after all the Glazers’ various re-financings, and Arsenal, whose £232 million debt effectively comprises the “mortgage” on the Emirates stadium.

As a result, Villa’s net interest payable is down to £1.2 million. As a comparison of what might have been with a different kind of American owner, Manchester United incurred £35 million of interest costs last season as the price of their leveraged buy-out.

Villa still clearly require the owner’s support, as seen by the 2014/15 cash flow. They made a small £2 million cash loss from operating activities after adding back non-cash items (player amortisation and depreciation), but then spent a net £15 million on players, £3 million on infrastructure investment and £1 million on interest payments. This was largely funded by £16 million of additional financing.

On top of the initial £66 million Lerner paid to acquire the club in 2006, he has put in over £300 million, split between £170 million of loans and £133 million of share capital. In addition, he has cancelled repayment of £182 million of loans, which is money he would only get back if he sold the club (and for a decent price).

Basically, all of the spare cash that Villa has had available since 2006 has come from Lerner’s resources. This has been used as follows: player purchases £135 million, funding operating losses £49 million, capital expenditure £42 million, interest payments £13 million and repayment of external loans £5 million.

Unlike some other American owners, Lerner also cannot be accused of hoarding cash, as Villa only have around £100k in their bank account. In stark contrast, Arsenal had £228 million and Manchester United £156 million.

According to the club, Villa should have no problems with Financial Fair Play: “From a regulatory perspective the club’s aggregated player service costs and image contract payments for the year ended 30 June 2015 are expected to comply with the Premier League’s short-term cost control rules and forecast earnings before tax for the three years ending 31 May 2017 are expected to comply with its profitability and sustainability rules.”

Lerner put the club up for sale almost two years ago in May 2014, lamenting that “the last several seasons have been a week-in, week-out battle”, but he has yet to find a buyer at his purported asking price of £150 million. Villa’s strategic report stated, “the Group remains for sale, but at the time of writing no active discussions were taking place.”

Little wonder, given Hollis’ description of the current state of play: “In football terms, this is a crisis. This is the worst position this club has been in for many a decade.” That’s pretty damning, but the new chairman’s not wrong.

"Don't look down"

The latest figures are simply awful: the largest loss in the Premier League, a decline in revenue, a wage bill that’s out of control, falling attendances, smallest cash balance in top flight, the list goes on and on.

Ironically, given that the club has effectively been supported by Lerner financially over the last few years, it feels like it really needs a change in ownership. Fox got it right when he said that “Villa is a proud and storied club which deserves to be among the elite in Europe”, but it is likely to have to start again in the Championship.

Hollis said that the new board is “going to do the things we need to do to get this club back to where it needs to be”, but there are plenty of examples of clubs with a great history (e.g. Nottingham Forest, Leeds United) that have struggled to gain promotion, while others have continued their fall from grace into League One (e.g. Wigan Athletic, Wolverhampton Wanderers).

Relegation might be the shock to the system that Villa need, but if they do go down, there are no guarantees that they will quickly bounce back.