Although slightly obscured by Leicester City’s extraordinary story, Tottenham have also made significant progress this season, quietly establishing themselves as highly credible contenders for the league title, while moving forward in the development of their new stadium.

They have built on the progress made in head coach Mauricio Pochettino’s first season in 2014/15, when Spurs finished fifth in the Premier League and reached the final of the Capital One Cup. After many years of managerial upheaval involving the varied, but ultimately underwhelming talents of Harry Redknapp, André Villas-Boas and Tim Sherwood, it looks like Spurs have finally found a good one in the young Argentinian.

As chairman Daniel Levy observed, “Mauricio and his coaching staff have created a great team spirit in a stable squad that encompasses both experience and youth. The results speak for themselves.” Not only does it look like Spurs will secure one of the elusive Champions League places, but their success has been built on an exciting brand of aggressive, pacy football, featuring many young talents, such as Harry Kane, Dele Alli and Eric Dier.

"Back on the Kane gang"

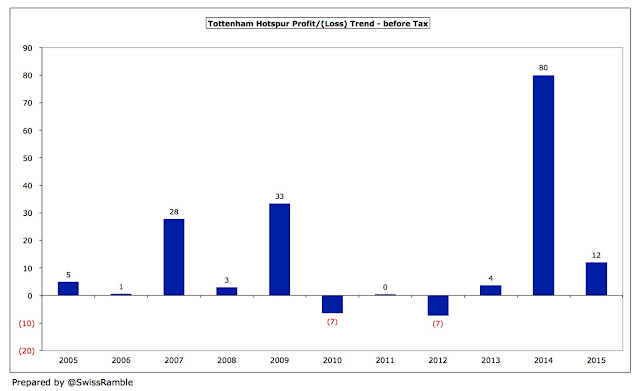

Tottenham’s improvement this season has not been at the expense of their finances, as they have just published another very solid set of financial results for the 2014/15 season with record revenue of £196 million and £12 million pre-tax profit (£9 million after tax).

Even though the profit before tax was £68 million lower than the previous season’s £80 million, that was a totally unprecedented figure, greatly enhanced by the blockbuster sale of Gareth Bale to Real Madrid. Indeed, profit on player sales decreased by £83 million from £104 million to £21 million.

On the other hand, revenue rose by £16 million (9%) from £180 million to £196 million, almost entirely driven by a £17 million (38%) increase in commercial income from £43 million to £60 million, including the first year of the new shirt sponsorship deal with AIA. Broadcasting was unchanged at £95 million, while match receipts were slightly lower at £41 million.

The wage bill was basically flat at £101 million, but other expenses increased by £6 million (15%) from £41 million to £47 million. Player amortisation was £3 million (7%) lower at £37 million, while the impairment charge was reduced by £7 million to £3 million.

In line with growing expenditure on the stadium construction, depreciation rose by £1 million to £6 million. Net interest payable was also £1 million higher at £5 million, largely due to a provision for early repayment of a loan.

Once again, Spurs booked exceptional charges for redundancy costs and onerous employment contracts. Last year’s £4.7 million was mainly for the pay-offs to Villas-Boas and his coaching staff, while the reasons for this year’s charge of £6.5 million are less clear, though it is likely that some will be a provision for paying-off Emmanuel Adebayor’s contract.

Tottenham’s pre-tax profit of £12 million is more than respectable, but is actually only the seventh highest in the Premier League in the 2014/15 season, behind Liverpool £60 million, Burnley £35 million, Newcastle United £32 million, Leicester City £26 million, Arsenal £25 million and Southampton £15 million.

Long gone are the days when Spurs were one of the few profitable clubs in the top flight. No, the Premier League is now a largely profitable environment with only five clubs losing money so far in 2014/15, thanks to the increasing TV deals allied with Financial Fair Play (FFP).

That said, there are still some appallingly run clubs that managed to lose a lot of money against all odds: step forward, Queens Park Rangers and Aston Villa, who somehow contrived to make losses of £46 million and £28 million respectively.

No football club is more aware than Tottenham of the impact that player sales can have on the bottom line, especially as they posted the highest Premier League profit in 2013/14 thanks to the highly lucrative Bale transfer. In 2014/15 it was Liverpool’s turn to benefit from a mega transfer, with the sale of Luis Suarez to Barcelona the main reason for the £56 million they earned from this activity.

Although Tottenham’s profits from player sales declined, they still generated £21 million of profits in 2014/15, including the transfers of Jake Livermore and Michael Dawson to Hull City, Sandro to QPR, Gylfi Sigurdsson and Kyle Naughton to Swansea City, and Zeki Fryers to Crystal Palace.

Of course, Spurs have always kept a close eye on their finances, so much so that they have only reported (small) losses twice in the last 11 years. Levy himself has commented, “Tottenham Hotspur have always been run on a rational basis. It’s one of the few clubs that has been consistently profitable.” In fact, Spurs have made aggregate profits of £146 million since 2007, including £96 million in the last three years alone.

Nevertheless, it should be acknowledged that much of that solid financial performance is down to player sales with Tottenham making an incredible £288 million from this activity in the last decade. On the one hand, Levy’s infamously tough negotiation skills have clearly reaped large financial rewards, but on the other hand, some supporters have expressed unhappiness that this turnover has weakened the team.

Levy explained the strategy thus, “Our pragmatic player trading has been important in the way we have run the business of the club and in getting us to the position where we have now been able to start work on a new stadium.” Indeed, without those player sales, Tottenham would have reported losses of £141 million.

Tottenham’s last significant profit before the Bale sale was the £33 million posted in 2009, which was also largely due to profits on player sales of £56 million with Dimitar Berbatov moving to Manchester United and Robbie Keane to Liverpool.

There should again be a fairly handsome profit on player sales in the next set of accounts following a high number of departures: Andros Townsend to Newcastle, Robert Soldado to Villarreal, Paulinho to Guangzhou Evergrande, Etienne Capoue to Watford, Benjamin Stambouli to Paris Saint Germain, Lewis Holtby to Hamburg, Vlad Chiriches to Napoli, Aaron Lennon to Everton and Younes Kaboul to Sunderland.

Tottenham’s reported profits will be increasingly impacted by property transactions, as a result of sales linked to the stadium development. The 2013 accounts already included £5.6 million profit on property disposals following a sale to another group company, while the 2015/16 accounts will include £8.6 million profit after selling the site of Brook House primary school (sales proceeds £11 million less net book value £2.6 million).

Given how important player trading is to Tottenham’s business model, it is worth exploring how football clubs account for transfers. The fundamental point is that when a club purchases a player the costs are spread over a few years, but any profit made from selling players is immediately booked to the accounts.

So, when a club buys a player, it does not show the full transfer fee in the accounts in that year, but writes-down the cost (evenly) over the length of the player’s contract. To illustrate how this works, if Spurs paid £25 million for a new player with a five-year contract, the annual expense would only be £5 million (£25 million divided by 5 years) in player amortisation (on top of wages).

However, when that player is sold, the club reports the profit as sales proceeds less any remaining value in the accounts. In our example, if the player were to be sold three years later for £32 million, the cash profit would be £7 million (£32 million less £25 million), but the accounting profit would be much higher at £22 million, as the club would have already booked £15 million of amortisation (3 years at £5 million).

This is horribly technical, but at its simplest, the more that a club spends on buying players, the higher its player amortisation. In this way, this increased at Tottenham from £25 million to £40 million in 2013/14 “due to the continued investment in the playing squad”, before falling back to £37 million in 2014/15, partly due to “the impairments of certain player registrations in the prior year”. This happens when the directors assess a player’s achievable sales price as less than the value in the accounts.

Tottenham’s player amortisation is a fair bit below the really big spenders like Manchester United, whose massive outlay under Moyes and van Gaal has driven their annual expense up to £100 million, Manchester City £70 million and Chelsea £69 million, but it is essentially in line with their revenue. It should rise next year following the purchases of Son, Clinton N’Jie, Toby Alderweireld, Kevin Wimmer and Kieran Trippier.

The other side of the player trading coin is that player values have also shot up, nearly doubling from £58 million in 2012 to £109 million in 2015, though this actually fell from £122 million in 2014.

Even though player trading (and particularly profits from player sales) have such an important impact on Tottenham’s bottom line, the club is still highly profitable from its core business, as shown by EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxation, Depreciation and Amortisation), which can be considered a proxy for the club’s profits excluding player trading. This has risen steadily in the last two seasons from £19 million in 2013 to £48 million in 2015.

That is not bad at all, but is still outpaced by the two Manchester clubs, United £120 million and City £83 million, Liverpool £73 million and Arsenal £63 million. Even though those clubs have much larger wage bills, they enjoy far higher revenue, so the net result is still better than Tottenham, which goes a long way to explain Spurs’ greater reliance on a player sales strategy.

Tottenham have grown their revenue by £83 million (74%) since 2009. Like most other Premier League clubs, much of this has simply been driven by the new TV deals with broadcasting income contributing £50 million of this growth. This can be seen by the increases in 2011 and 2014 in line with the new three-year cycles of the Premier League TV deals. The rise to £164 million in 2011 was also boosted by £37 million from the Champions League (prize money and gate receipts).

Commercial income has also begun to show some reasonable growth, rising £31 million in that six-year period, with more than half of the increase coming in 2015 alone. However, match receipts have essentially been flat, rising just 4%, once again emphasising the need for a new stadium.

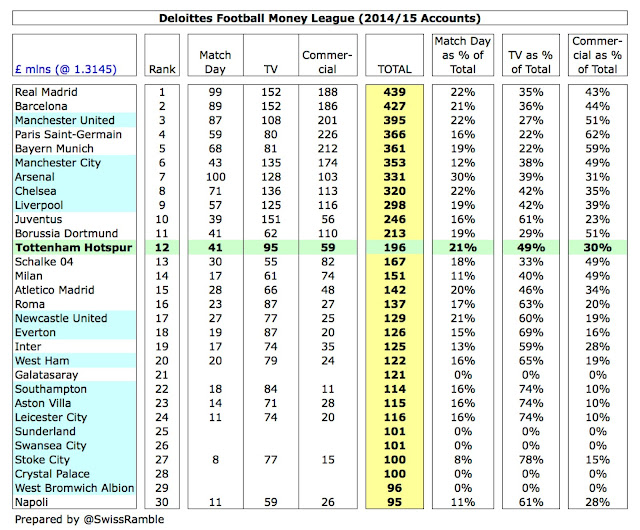

Even after the 2015 revenue growth, Tottenham remain in sixth place in the English revenue league with £196 million. To place this into context, they are still around £200 million behind Manchester United (£395 million), £130 million lower than North London rivals Arsenal (£329 million) and £100 million below Liverpool (£298 million).

On the other hand, at the same time they are a long way ahead of their other Premier League rivals, being £70-75 million higher than Newcastle United (£129 million), Everton (£126 million) and West Ham (£121 million). As the late, great Ian Dury might have said, Spurs are basically the “Inbetweenies” of the Premier League, struggling to reach the highest echelon, but comfortably beyond the chasing pack.

Not only that, but their closest rivals (at least from a revenue perspective) are growing their revenue at a faster rate. While Tottenham increased revenue by £15 million (9%) in 2014/15, Arsenal’s rose by £31 million (10%) and Liverpool’s by £42 million (17%). Clearly, Champions League participation was a major factor for Liverpool (and also explains Manchester United’s significant decrease), but even so.

For the second year in a row, Tottenham moved up a place in the Deloitte Money League to 12th, just behind Juventus and Borussia Dortmund, but over-taking Milan, partly helped by the strengthening of Sterling against the Euro.

That’s obviously a fine accomplishment, but the Money League highlights a new challenge for clubs like Spurs, as no fewer than 17 Premier League clubs feature in the top 30 clubs worldwide by revenue, thanks to the TV deal. This means that the mid-tier clubs have more purchasing power than ever before, so are more competitive as a consequence, as amply demonstrated by Leicester City.

If we compare Tottenham’s revenue with the other clubs in the Deloitte Money League top twelve, this highlights their shortfall on match day income, but there is a far larger issue with commercial income. Tottenham’s recent growth to £60 million is praiseworthy, but this is still substantially lower than almost all of the elite clubs.

Granted, the £166 million shortfall against PSG (£60 million vs. £226 million) is largely due to the French club’s “friendly” agreement with the Qatar Tourist Authority, but there are still major gaps to the other clubs in commercial terms: Bayern Munich £152 million, Manchester United £141 million, Real Madrid £129 million, Barcelona £126 million and Manchester City £114 million.

Given the well-known TV riches in the Premier League, Tottenham fans might also be puzzled by their lower broadcasting revenue, but this is essentially due to the lack of Champions League money. In terms of domestic TV revenue, Spurs are very competitive with their £91 million only surpassed by other leading English clubs and the Spanish giants, Real Madrid and Barcelona, who benefit from individual deals.

Following the rise in 2015, commercial income’s share of total revenue has increased from 24% to 30%, though broadcasting remains the most important revenue stream with 49% (down from 52%). Match day income also fell from 24% to 21%.

Despite finishing a place higher in fifth, Tottenham’s share of the Premier League TV money slightly decreased by £1 million from £90 million to £89 million in 2014/15, as the additional merit payment was offset by a lower facility fee, as they were only shown live 18 times (compared to the previous season’s 24).

All other elements of the central TV deal are equally distributed among the 20 Premier League clubs: the remaining 50% of the domestic deal, 100% of the overseas deals and central commercial revenue.

Tottenham will see increases here in the future. First, the 2015/16 distribution will benefit from this season’s success, as they should finish at least third, while they will be broadcast live around 27 times (based on current scheduling). That should deliver an additional £9 million.

Then, there will be a substantial increase from the mega Premier League TV deal starting in 2016/17. My estimates suggest that Tottenham’s 5th place would be worth an additional £49 million under the new contract, taking the annual payment up to an incredible £138 million. This is based on the contracted 70% increase in the domestic deal and an assumed 30% increase in the overseas deals (though this might be a bit conservative, given some of the deals announced to date).

The other main element of broadcasting revenue is European competition with Tottenham receiving €6.1 million (£7.1 million including gate receipts) for reaching the last 32 in the Europa League where they were eliminated by Fiorentina. This was much lower than the Champions League, where the four English clubs earned an average of €39 million, ranging from Manchester City’s €46 million to Liverpool’s €34 million. This underlines the size of the prize assuming that Tottenham do cement their Champions league qualification.

Here it is worth noting the importance of the final league placing to the TV (market) pool calculation. Half of the payment depends on how far a club progresses in the Champions League, but the other half is based on where the club finished in the previous season’s Premier League, with the winners receiving a 40% share, second place 30% share, third 20% and fourth 10%.

Nobody needs to explain the impact that the Champions League can have on revenue to Tottenham, as their run to the Champions League quarter-finals before being eliminated by Real Madrid in 2010/11 generated €31 million of prize money (£37.1 million including gate receipts), but the club’s failure to qualify for Europe’s premier tournament more than once in the last five years has really hurt their bank balance.

In that period, Tottenham have earned €51 million from Europe, which is around €90 to €180 million less than the top four received – and that does not include revenue from additional fixtures and sponsorship clauses. That’s a huge competitive disadvantage and has made it all the more difficult for Spurs to break into the Champions League qualifying places.

It must have therefore been particularly galling when they finished fourth in the Premier League in 2012, which would normally have guaranteed a place in the Champions League qualifying round, only to be deprived of this opportunity following Chelsea’s unlikely victory against Bayern Munich.

The financial significance of a top four placing is even more pronounced from this season with the new Champions League TV deal worth an additional 40-50% for participation bonuses and prize money and further significant growth in the market pool thanks to BT Sports paying more than Sky/ITV for live games.

Tottenham’s match day revenue fell slightly by £1.2 million (3%) from £42.4 million to £41.2million. Premier League gate receipts were flat, while income from domestic cup competitions rose as a result of reaching the Capital One cup final, but there was a reduction in the Europa League receipts.

Tottenham generate less than half of the revenue of their rivals Manchester United and Arsenal, who earn £90-100 million a season in their far larger stadiums, despite charging the second highest season ticket prices in England (only behind Arsenal).

However, they have frozen ticket prices for three seasons in a row, noting that “the club fully recognises the need to keep football affordable and facilitate a fantastic atmosphere in the ground”, though pressure from supporters was required before they dropped the idea of a proposed 2% increase for 2016/17.

In fact, Tottenham have only the 9th highest attendance in the Premier League with around 36,000, behind the likes of Sunderland, Chelsea and Everton, but this is effectively full capacity with the club selling out all Premier League home games. This underlines the need for the new, larger stadium, which would satisfy a waiting list that has risen to over 50,000.

As Levy put it, “In respect of driving higher revenues in order to enable greater investment in players, it is clearly evident that we need a ‘game changer’ to lift this club to the next level - namely an increased capacity stadium. Currently we are competing for Champions League qualification whilst driving revenue in the smallest stadium of the top six clubs in the Premier League. The new stadium is, therefore, critical.”

The proposal for a 61,000 capacity stadium adjacent to White Hart Lane was finally approved in December 2015 by Haringey Council. This will be the largest club ground in London, exceeding the capacity at Arsenal by around 1,000, and will be built as a multi-use facility in order to maximise potential revenue.

"Hit the ground running"

It will therefore have a fully retractable grass pitch, allowing a synthetic surface to be used for other events. Indeed, the club has already signed a 10-year partnership with the NFL to host a minimum of two regular games a season.

The aim is to have the new stadium ready for the 2018/19 season, though Spurs will have to move to temporary premises for the 2017/18 season. Their preferred option would be Wembley (at an annual rent of some £15 million), but Chelsea are also keen on the national stadium while Stamford Bridge is being redeveloped, so they might have to look elsewhere with the MK Dons Stadium also being considered.

This is a massive project with the latest cost projections up to £500 million for the stadium, but between £675 million and £750 million for the entire development, including land purchase, residential property, hotel and other facilities, which is double the original estimate.

Tottenham have already spent £100 million, while financial adviser Rothschild have arranged £350 million of loans from three banks, leaving a gap of £300 million to be funded (assuming the higher cost).

"Shine on"

Tottenham will hope to emulate Arsenal’s model when constructing the Emirates Stadium by signing front-loaded commercial deals, including naming rights. There has been talk of £30 million a season, though that sounds ambitious, even if the club says it has “received expressions of interest from credible counterparties.”

Other options include a further round of debt financing or even an equity investment, but the latter seems unlikely, as that might complicate a future sale and the current owners would probably prefer to sell after the stadium is completed and the value has increased.

According to press reports, the club has estimated that the new stadium would generate an additional £28 million match day income a year, largely from corporate hospitality, though this seems a little on the low side, given the significant capacity increase and the high ticket prices.

They have also emphasised the difficulties in completing this project. Levy commented, “We know that our North London neighbours experienced delays and setbacks during the delivery of their stadium and their challenges were far less than ours with no site constraints and with significant enabling development.”

This was confirmed by Pochettino: “I have read a lot about Arsène Wenger saying the toughest period for Arsenal was in the period that they built their stadium and I think the people need to know that this is a very tough period for us.” In investment terms, this is the classic risk and reward situation.

As we have seen, the other area that Tottenham need to address is commercial income. Even after an impressive increase of £17 million (38%) from £43 million to £60 million, this is still a long way below the top five clubs: Manchester United £197 million, Manchester City £173 million, Liverpool £116 million, Chelsea £108 million and Arsenal £103 million.

Tottenham have always behind the “big boys” commercially, but the magnitude of this disparity is a relatively recent phenomenon. Since 2012 Tottenham have the lowest growth of the top six English clubs, both in absolute and percentage terms, with an increase of only £18 million (44%). As a painful comparative, in the same period Arsenal have grown by £51 million to £103 million. Mind the gap, indeed.

The 2014/15 season was the first in a five-year shirt sponsorship deal with AIA, an insurance services provider, worth around £16 million a season. That’s not too bad, but is a lot lower than Manchester United £47 million (Chevrolet), Chelsea (Yokohama) £40 million and Arsenal (Emirates) £30 million.

It’s a similar story with Tottenham’s kit supplier, Under Armour, who have a five-year deal worth a reported £10 million a year, running until the end of the 2016/17 season. Again, that’s pretty good, but it pales into significance next to Manchester United’s “largest kit manufacture sponsorship deal in sport” with Adidas, which is worth an average of £75 million a year, or Arsenal’s Puma deal (£30 million).

That said, there have been reports in the media about Spurs trying to negotiate a £30 million agreement with Nike, which would make a big difference to the comparatives. Of course, if Spurs start to deliver success on the pitch, this would boost them commercially, e.g. sponsorship contracts are likely to include more money for Champions league participation.

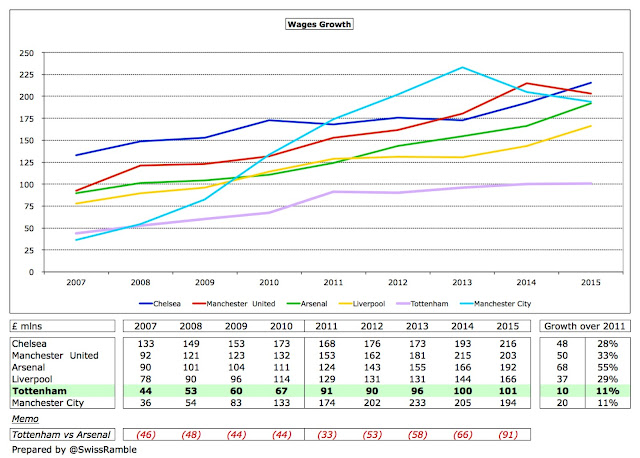

Tottenham’s wage bill rose vey slightly by £0.4 million from £100.4 million to £100.8 million, reducing the wages to turnover ratio from 56% to 51%, the lowest since the 46% achieved in 2008. Wages have only risen by a cumulative £10 million (11%) in the last five years, which is a striking demonstration of Spurs’ ability to control costs.

The last time that there was a substantial increase came in 2011, when the wage bill shot up from £67 million to £91 million. This was partly due to the club “augmenting its squad of players to be able to compete both at home and in Europe”, but also an attempt to retain core players on long-term deals with higher, competitive salaries.

Mirroring revenue, Tottenham’s wage bill is much lower than the top five clubs: Chelsea £216 million, Manchester United £203 million, Manchester City £194 million, Arsenal £192 million and Liverpool £166 million. In other words, Tottenham have largely performed in line with expectation, though are punching above their weight this season.

In this way, Tottenham’s wages to turnover ratio of 51% is one of the lowest (i.e. best) in the Premier League, only matched by Manchester United and Newcastle United (also 51%) and beaten by Burnley (37%). Despite their much higher revenue, Arsenal’s wages to turnover ratio was worse at 56%.

Since 2011, Spurs have managed to keep their wage bill in a tight range of £90-100 million, but other clubs have continued to spend ever-increasing sums on players. In particular, in that period Arsenal’s wage bill has grown by £68 million (55%) to £192 million, increasing the gap to Spurs from £33 million to £91 million. However, given the Gunners’ performances this season, you could hardly call that money well spent.

Next year’s accounts will be interesting, as the wage bill will benefit from the departure of some high earners (e.g. Adebayor, Soldado and Paulinho), replaced by younger, cheaper players, but there should also be higher bonus payments following this season’s improved results.

It’s worth noting that the directors’ remuneration continues to increase with Daniel Levy receiving £2.6 million, up from £2.2 million. This means that his remuneration has grown by nearly £1 million (or 57%) in just two years, which is not too shabby.

There has been a fairly dramatic turnaround in Tottenham’s transfer activity in the last five seasons with average annual net sales of £11 million, compared to average net spend of £19 million in the preceding five seasons (which you could loosely call the “Redknapp effect”).

In fairness, there has been over £250 million of gross spend in this period, but on the whole Spurs have been a selling club in recent times, only splashing the cash after a player has been sold. That’s not always their call obviously, as sometimes it’s the player that wants to leave, but, as Levy explained, “Tottenham is not a club that can consistently pay £50 million for a player. We have to make our players.”

In fact, every other club in the Premier League has spent more than Tottenham in the last five seasons, which is an unsurprising statistic, given that they are the only club with net sales (of £54 million). It is particularly telling how much more Spurs’ rivals for a Champions League place have spent in this period: Manchester City £303 million, Manchester United £288 million, Chelsea £199 million, Liverpool £149 million and even the traditionally frugal Arsenal £102 million.

Obviously, money is not the only ingredient in the recipe to build a good squad and Spurs have made some really astute, value signings, e.g. Dele Alli and Eric Dier, while Levy has pointed out that the lack of big money signings has also given the young players “space to flourish”.

Pochettino is fully on message: “You need to realise that to improve our squad today is a very difficult job. I have been very clear that we would only add players that we felt would improve us and if any one player was not possible then I prefer we do not add for the sake of it.”

That said, it’s difficult for Tottenham to keep up with the sort of financial firepower employed by the elite clubs and the concern must be that there will be even less cash available to spend in the transfer market while the new stadium is being built. Although Levy has promised to ring-fence a percentage of cash for buying new players, Tottenham fans need only look at their North London neighbours to see the impact while a new stadium is being financed.

The club has moved from net funds of £3.2 million the previous year to net debt of £20.8 million, though gross debt actually fell from £35.4 to £31.5 million, as cash decreased from £38.5 million to £10.7 million. The debt comprises a £13 million Investec bank facility repayable over five years tracking LIBOR and £18.5 million of 7.29% secured loan notes repayable in equal installments over 16 years from September 2007.

Daniel Levy has previously observed, “there is hardly a transfer concluded across Europe which doesn’t include staged payments”, and that is certainly demonstrated in Tottenham’s accounts. They owe other clubs £26 million, while they are themselves owed £53 million (largely due to the Bale sale) – though they have received £23 million of this since the balance sheet date.

Similarly, Tottenham have contingent liabilities of £13 million, which are potentially payable based on the success of the team and individual players, but also a contingent asset of £17 million.

Tottenham’s gross debt of £32 million is currently among the lowest in the Premier League, considerably below Manchester United, who still have £444 million of borrowings even after all the Glazers’ various re-financings, and Arsenal, whose £232 million debt effectively comprises the “mortgage” on the Emirates stadium.

As the new stadium progresses, this situation will obviously change, meaning Spurs will have one of the largest debts in the top flight. To give an example of the financial impact, Arsenal are even now still paying around £19 million a year in interest and loan repayments.

Tottenham have generated a lot of cash in recent years, though this would have been even higher if clubs had paid for transfers upfront, as we can see from the cash flow difference in net player purchases compared to the actual fees.

In 2015 they made £41 million from operating activities, having added back non-cash items like player amortisation, depreciation and impairment, but then invested £42 million in infrastructure and £11 million in player registrations. They also bought-back £10 million of preference shares, repaid £4 million of loans, made £2 million of interest payments and £1 million of tax. This produced the £28 million reduction in the cash balance.

Since 2007 Tottenham have had £415 million of available cash, largely generated from their own operating activities (£328 million), but also equity contributions from owners ENIC (£44 million) and long-term debt financing (£19 million) with the remainder coming from reducing the cash balance (£24 million).

The majority of that surplus cash £212 million (51%) has been invested in fixed assets, essentially the new stadium and the new training centre in Enfield. A further £157 million has gone on player purchases, £28 million on interest payments, £10 million to the taxman and £7 million dividends.

Tottenham’s need for external financing for the new stadium is shown by their relatively low cash balance of £11 million, compared to Arsenal £228 million and Manchester United £156 million. Arsenal’s high balance is down to their lack of appetite for spending, while United are a cash machine.

There has been some noise about the possibility of the club being sold, including an approach from US private investment company Cain Hoy to buy the club on behalf of a group of American businessmen, but there have been no concrete proposals. There might be more interest in the future, as overseas investors will be attracted by the booming TV rights, but they might be scared off by the price asked by Levy, which is rumoured to be an “aspirational” £800 million, and the investment required to finance the new stadium.

"From a whisper to a scream"

Evidently, a club as profitable as Tottenham has no issues with the Financial Fair Play (FFP) regulations, though Levy has stressed the implications in terms of revenue generation: “We are all eager to be challenging at a higher level. Whilst the popular view may be to spend money in excess of earnings or find a philanthropic investor to fund transfers, those scenarios are simply not possible under the new world of Financial Fair Play rules, whereby clubs can only spend revenues generated through operations.”

Going forward, Tottenham’s revenue will indeed rise, thanks to Champions League qualification and the new Premier League TV deal, but they will still struggle financially against the European elite.

Nevertheless, Levy spoke with optimism: “We are continuing with an ambitious growth strategy. Our player development, on pitch performances, enhancements to our highly rated Training Centre and commencement of the new stadium scheme which will also host NFL, signify an exciting future for the club.”

"Clap Your Hands Say Yeah"

There will have to be a tricky balancing act between the financial demands imposed by the stadium construction and the need to improve the squad, but it does feel as if something has changed at White Hart Lane. The team is no longer so, well, “Spursy”, and they have an excellent manager in Pochettino.

The Argentinian himself sounds bullish about the future, “When you compare Tottenham with big sides, people can see our approach is for the long term. We have the youngest squad in the Premier League, yet here we are fighting for the title. The project is fantastic, because we are ahead of the programme – we are only going to get better.”

They will need to hang on to their stars to match their ambitions, avoiding the temptation to cash in on the likes of Kane and Alli, so they are no longer considered a stepping-stone to more powerful clubs. If they can do that, then maybe they can genuinely dare to dream.

They will need to hang on to their stars to match their ambitions, avoiding the temptation to cash in on the likes of Kane and Alli, so they are no longer considered a stepping-stone to more powerful clubs. If they can do that, then maybe they can genuinely dare to dream.

0 comments:

Post a Comment