It is a sign of how far Brentford have progressed that many of their supporters were somewhat disappointed with their ninth place finish in this season’s Championship. Their expectations had been raised by the Bees reaching the play-offs the previous campaign, which chairman Cliff Crown described as “our most successful in living memory.”

This was fair comment, given that Brentford had finished fifth in their first season in the Championship for 22 years, and were plying their trade in League Two as recently as 2009. In fact, Brentford had been languishing outside the top two divisions for all but one season in near on 70 years before gaining automatic promotion from League One in 2014, which amply demonstrated the club’s ability to bounce back after the heartbreaking defeat to Yeovil Town in the previous season’s play-off final.

As Brentford owner Matthew Benham noted, “We’ve come a long way in a fairly short space of time and that can’t be forgotten.” Crown, in turn, described the 2015/16 season as one of “consolidation, before we kick on again.” That seems reasonable enough, considering the Bees’ impressive finishing run, when they won seven of their last nine games (though that did follow a less enjoyable run of 10 defeats in 13 games).

"Judgement Day"

On the face of it, the reason for Brentford going backwards was fairly straightforward, namely the departure of manager Mark Warburton, who had seemed to be working a minor miracle by guiding the club to an impressive fifth place the previous season. A former city trader, Warburton had been promoted from his former role as Brentford’s sporting director to manager by Benham, but his contract was not renewed following a disagreement about the future philosophy of the club.

Warburton was replaced by Marinus Dijkhuizen, the Excelsior manager, in June 2015, but he left just four months later after a miserable time with Benham himself admitting, “On the pitch, the level of the team is not where it was 12 months ago.”

He added, “Very quickly we realised that he wasn’t going to be our guy. But to be fair to Marinus, he was also dealt a bad hand. Such a vast turnover of players. Massive upheaval.” However, he did also note, “There was a huge cultural divide between him and the players.”

"Happy Jake"

In fairness to the Dutchman, not only did he lose star striker, Andre Gray, who was sold to Burnley, but also had to cope with a disastrous, newly laid pitch that contributed to injuries to a number of players, including record signing Andreas Bjelland, who was ruled out for the season.

Lee Carsley, the Development Squad manger, was briefly promoted to Head Coach, before making way for the current incumbent, Dean Smith, who arrived from Walsall in November. Despite losing a couple of key players in the January transfer window (James Tarkowski to Burnley and Toumani Diagouraga to Leeds United), Smith led the team to a top ten finish.

Given all the issues experienced this season, there is cause for optimism in the future. As co-director of football Phil Giles put it, “There's been so much happening this season with injuries, pitches, three managers, players striking, broken legs; all this kind of stuff. It can't happen every season surely.”

Overall, it does look like all the millions invested by Benham are beginning to pay off. He is a lifelong Brentford fan, who owns two betting and statistic companies, Smartodds and Matchbook. His initial involvement came in 2006, when the supporters trust, Bees United, needed another £500k to complete their takeover.

"Good Vibrations"

At that time, Brentford were in deep financial trouble. As former Chairman Greg Dyke said, “It is fair to say that without Bees United there would probably not have been a club for Matthew to take over.”

That said, Benham is the man that has brought financial stability to Brentford, first by pledging to inject a minimum of £5 million of new capital between 2009 and 2014, then by taking full control in June 2012, when he took over Bees United’s 96% shareholding.

Dyke again: “The days of spending monies that we did not have and borrowing monies that we could not repay are long gone for this club. Matthew’s monies have removed us from the hand to mouth existence that we endured.”

In fact, Benham’s financial commitment to Brentford was up to £76 million as at June 2015. The long-term aim is clearly to create a sustainable club, but for the time being its ability to maintain a competitive challenge in the Championship is almost entirely reliant on the owner’s generosity.

"He blinded me with science"

In addition, Benham’s background has led to Brentford being regarded as England’s prime exponents of statistical analysis. This approach was pioneered at FC Midtjylland, who won the Danish league in 2015, where Benham is the majority shareholder.

Benham himself does not appear completely comfortable with the “Moneyball” label being applied to this strategy, as it is so often misused and misunderstood: “Everyone came to the conclusion that our methods consisted only of maths and nothing else. However, there has always been a mix between maths and traditional coaching. Analytics has been responsible for identifying some of our most successful players. But analytics are one part of a very big process.”

The approach was further explained by Rasmus Ankersen, Brentford’s other co-director of football: “We really believe analytics can make a difference and have a role to play in football and will have a bigger role to play in the future. But no matter how many times we say we also do all the traditional stuff, people don’t listen because the narrative is set. We don’t disrespect or disregard traditional scouting or coaching at all.”

He added, “Brentford and Midtjylland are small clubs with small budgets and that means you’ve got to think differently. If you just do the same as the other team then money becomes the decisive factor and we will lose, so we have got to take a different approach. Analytics is a different weapon. We had to go down that route to find an edge.”

Brentford’s challenge was highlighted by their 2014/15 financial results, which saw their loss nearly double from £7.7 million to a hefty £14.7 million, despite revenue rising by £5.5 million to a record £10.0 million following promotion to the Championship.

All three revenue streams increased: (a) broadcasting rose £3.4 million from £1.1 million to £4.4 million, thanks to the higher TV deal in the Championship; (b) ticketing shot up £1.4 million (81%) from £1.7 million to £3.1 million; (c) commercial was up £0.7 million (44%) from £1.7 million to £2.4 million.

However, wages also surged by £7.8 million (78%) from £10.0 million to £17.7 million, which the club said was “required to not only ensure survival but compete in the Championship”. In addition, a significant element was “as a result of bonuses paid out based on the first team’s league position”.

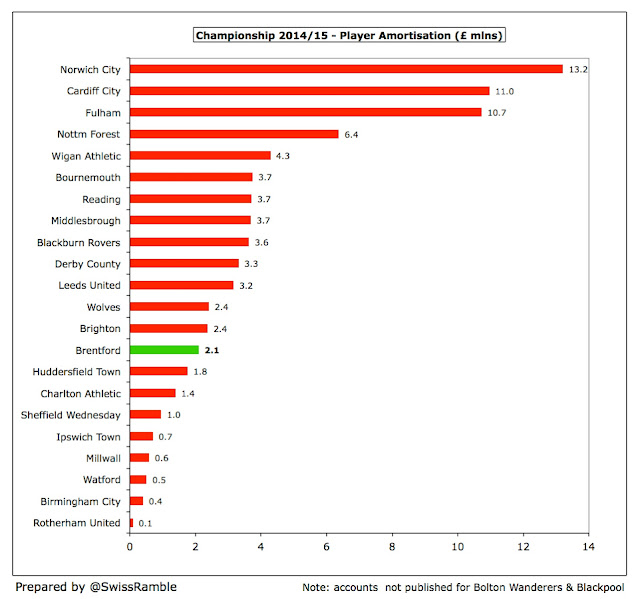

In addition, player amortisation was £1.8 million higher at £2.1 million, while other expenses climbed £1.1 million to £7.3 million.

Profit from player sales increased by £1.4 million from £0.6 million to £2.0 million, but other operating income (unexplained) fell by £3.1 million from £3.9 million to £0.9 million.

It should be noted that Brentford have changed the way that they account for player trading. In the past, the club wrote-off transfer fees as they occurred, but they now capitalise player registration costs and amortise charges over the length of the contract (as do the vast majority of football clubs). This has resulted in a restatement of the 2014 comparative, but, interestingly, this does not explain why the revenue figure has also changed.

Although Brentford’s £15 million loss is clearly not great, it is by no means the worst in the Championship, having been “beaten” by Bournemouth £39 million, Fulham £27 million, Nottingham Forest £22 million and Blackburn Rovers £17 million. The harsh reality is that hardly any clubs are profitable in the Championship with only six making money in 2014/15 – and most of those are due to special factors.

Ipswich Town were the most profitable with £5 million, but that included £12 million profit on player sales. Cardiff’s £4 million was boosted by £26 million credits from their owner writing-off some loans and accrued interest. Reading’s £3 million was largely due to an £11 million revaluation of land around their stadium. Birmingham City and Wolverhampton Wanderers both made £1 million, but were helped by £10 million of parachute payments apiece.

So the only club to make money without the benefit of once-off positives was Rotherham United, who basically just broke even – and ended up avoiding relegation to League One by a single place.

Of course, losses are nothing new for Brentford, though there has been a clear willingness to accept higher losses since Benham came on board. In the five years up to 2010, the annual losses were kept down to £1 million or lower, but in the five years since then Brentford have reported aggregate losses of £36 million, averaging £7 million a season.

The approach was outlined by Crown in 2013: “The board continues to run the club with a level of losses commensurate with the capital injections by Matthew Benham. We believe that this is the correct strategy in a results oriented business and one which involves a prudent approach to the level of risk to the financial security of the club. The continuing losses are accepted by Matthew and your board as the price to pay to reach our goals.”

That said, Benham explained that “It wasn’t sustainable for us to continue making such heavy losses as we were last season. But off the pitch, we (now) have a more sustainable structure. The club isn’t operating anywhere near the loss it was operating at 12 months ago.”

Part of that improvement will have been due to profits made from player sales. These can have a major impact on a football club’s bottom line, but Brentford only made £2 million from this activity in 2014/15, presumably for the sale of Adam Forshaw to Wigan Athletic.

In fairness, this is not an enormous money-spinner outside the Premier League, though some clubs made a lot more than Brentford here: Norwich City £14 million, followed by Ipswich £12 million, Leeds United £10 million and Cardiff City £10 million.

Actually, that £2 million was the highest amount that Brentford have made from player disposals for ages, accounting for almost 50% of the profits from player sales in the last nine years.

That is all going to change in the 2015/16 accounts with the lucrative sales of Andre Gray, Moses Odubajo, James Tarkowski, Stuart Dallas, Will Grigg and Toumani Diagouraga, which should bring in at least £15 million of profits.

Crown explained the thinking behind these departures: “Sometimes we lose players that we would rather keep – whether for offers that the leaving players feel they can’t refuse, and more recently for the slightly more practical purposes of complying with the League’s Financial Fair Play (FFP) regulations.”

This was echoed by Benham: “We have to cut our cloth accordingly… which unfortunately includes having to accept big bids for our best players from time to time.”

At least players are now leaving for big money rather than peanuts. The club has also got smarter about structuring its transfers, as it has been reported that they will earn around £3.5 million in add-ons on the Gray/Tarkowski deals as a result of Burnley’s promotion to the Premier League.

To get an idea of underlying profitability, football clubs often look at EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Depreciation and Amortisation), as this strips out player trading and non-cash items. Again, Brentford had one of the lowest with their minus £14 million EBITDA only better than Bournemouth minus £25 million, Nottingham Forest minus £20 million and Blackburn Rovers minus £15 million.

To be fair, only three clubs had a positive EBITDA in the 2014/15 Championship (Wolves, Birmingham City and Rotherham) and none of those clubs generated more than £1.5 million. In stark contrast, in the Premier League only one club (QPR) reported a negative EBITDA, which is testament to the earning power in the top flight.

Brentford’s revenue has increased in line with the club’s rise through the divisions: £3.0 million in League Two in 2009, £4.4 million in League One in 2014, and £10.0 million in the Championship in 2015. As Crown said after the promotion to League One, “it was important for the club’s long-term future to get promoted as soon as possible.”

One other important driver for revenue movements before promotion to the Championship was progress in the Cup competitions, e.g. 2013 was boosted by taking Chelsea to a replay in the fourth round of the FA Cup.

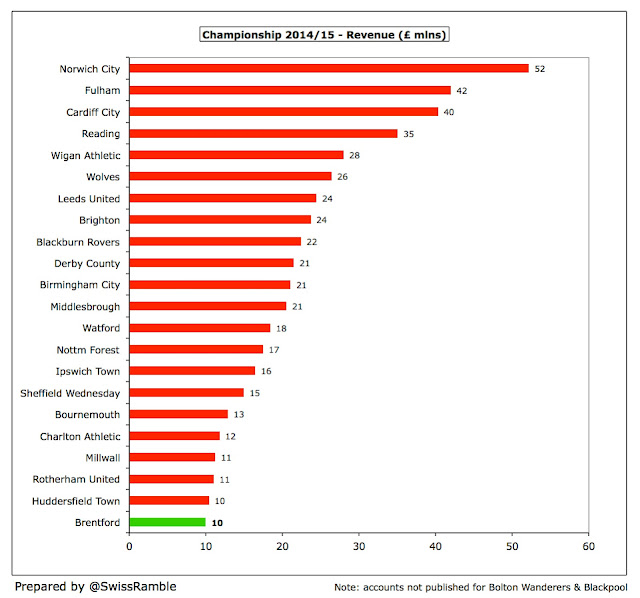

However, Brentford’s revenue was nowhere near the big hitters in the Championship. In fact, it was the smallest in the division in 2014/15 at £10 million. To place this into perspective, four clubs enjoyed revenue higher than £35 million (over £25 million more than Brentford): Norwich City £52 million, Fulham £42 million, Cardiff City £40 million and Reading £35 million.

Benham is acutely aware of this structural imbalance: “You have to remember, our revenue is very low. So we can’t ‘spend, spend, spend’ like other teams do. We have to be realistic. We have the lowest revenue in the Championship by far.”

This alone explains Brentford’s desire to find an edge by better use of analytics, as it’s a competitive necessity. Given their revenue level, Brentford have punched well above their weight in finishing 5th and 9th in their two seasons in the Championship.

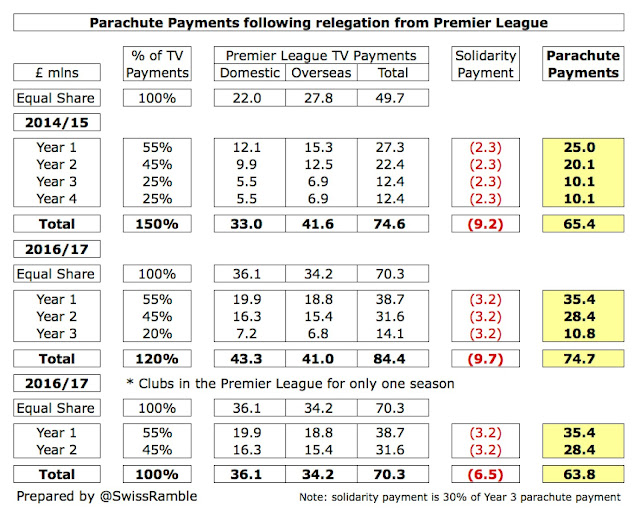

Of course, these revenue figures are distorted by the parachute payments made to those clubs relegated from the Premier League, e.g. in 2014/15 this was worth £25 million in the first year of relegation.

If we were to exclude this disparity, then the revenue differentials would be smaller, but Brentford would still be rock bottom of the league table, behind the likes of Wigan Athletic, Huddersfield Town, Rotherham United and Millwall – and two of those clubs ended up being relegated.

The increasing importance of TV revenue higher up the football pyramid is seen by Brentford’s revenue mix. In the Championship, broadcasting accounted for 45% of their total revenue, compared to just 24% in League One. As a result, match day’s share fell from 38% to 31% and commercial decreased from 38% to 24%.

In the Championship most clubs receive the same annual sum for TV, regardless of where they finish in the league, amounting to just £4 million of central distributions: £1.7 million from the Football League pool and a £2.3 million solidarity payment from the Premier League.

However, the clear importance of parachute payments is once again highlighted in this revenue stream, greatly influencing the top eight earners, though it should be noted that clubs receiving parachute payments do not also receive solidarity payments. As a comparison, Brentford’s broadcasting income was £4.4 million, while Fulham earned nearly £30 million.

Looking at the television distributions in the top flight, the massive financial chasm between England’s top two leagues becomes evident with Premier League clubs receiving between £65 million and £99 million, compared to the £4 million in the Championship. In other words, it would take a Championship club more than 15 years to earn the same amount as the bottom placed club in the Premier League.

The size of the prize goes a long way towards explaining the loss-making behaviour of many Championship clubs. As Benham observed, “If we get into the Premier League, things become easier because of the TV deal money.”

This is even more the case with the astonishing new TV deal that starts in 2016/17, which will be worth an additional £30-50 million a year, to each club depending on where they finish in the table. For example, I have (conservatively) estimated that the club finishing bottom in the Premier League next season will receive £92 million, which is £86 million more than a Championship club not receiving parachute payments.

From 2016/17 parachute payments will be higher, though clubs will only receive these for three seasons after relegation. My estimate is £75 million, based on the percentages advised by the Premier League (year 1 – £35 million, year 2 – £28 million and year 3 – £11 million). Up to now, these have been worth £65 million over four years: year 1 – £25 million, year 2 – £20 million and £10 million in each of years 3 and 4.

There are some arguments in favour of these payments, namely that it encourages clubs promoted to the Premier League to invest to compete, safe in the knowledge that if the worst happens and they do end up relegated at the end of the season, then there is a safety net. However, they do undoubtedly create a significant revenue disadvantage in the Championship for clubs like Brentford.

Crown has openly stated that Brentford’s goal is “sustainable Premier League football”, but Benham’s ambitions don’t stop there, as he has noted that the new deal “to an extent levels the playing field”, as seen by the improved performances this season of clubs like Southampton, West Ham and, of course, Leicester City.

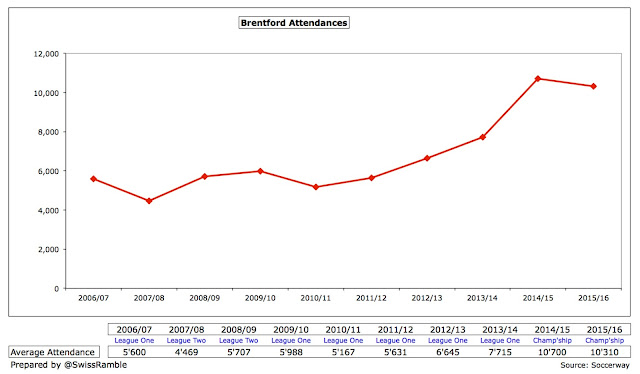

Despite rising 81% to £3.1 million, Brentford had one of the lowest match day incomes in the Championship, only ahead of Huddersfield Town £3.1 million, Rotherham £2.6 million and Wigan Athletic £2.4 million. This was far lower than clubs like Norwich City £10.7 million, Brighton £9.8 million and Leeds United £8.8 million.

This was even though attendances increased from 7,715 to 10,700 in 2014/15 with the sale of season tickets almost doubling to 5,641. This was 140% higher than the 4,469 average in League Two in 2007/08. There has been a dip in attendances 2015/16 to 10,310, which was only ahead of Rotherham – and some 2,300 behind Huddersfield Town, the next lowest club.

So Brentford’s average attendance is still one of the smallest in the Championship, though it is a similar level to Bournemouth who managed to gain promotion despite this disadvantage. Interestingly, the south coast club operated a similar strategy to Brentford, effectively speculating to accumulate, as the club’s owner heavily financed their attempts to go up.

Brentford have some of the lowest ticket prices in the Championship, especially at the important cheaper end, as explained by the board: “We took a conscious decision to keep season tickets and match day prices to a level that would reward all those who had supported us through so many previous seasons.” Moreover, season ticket prices have been frozen for the 2016/17 season in line with the club’s views on affordability.

The club’s income is clearly limited by the 12,300 capacity of Griffin Park, hence the plans to build a new 20,000 capacity stadium at Lionel Road. The club has acquired the site and has planning permission, but needs to buy one remaining piece of land before any work can start.

This is subject to a Compulsory Purchase Order, but the tribunal still needs to set the price. Even though the land is only valued at £2.5 million, Brentford have offered £6.25 million in an attempt to accelerate the process (the owners are apparently looking for £8.5 million).

The club has admitted that this is a very complex development, including not only the construction of a new stadium, but also a hotel and over 900 apartments that will help fund the development (along with the sale of Griffin Park).

"Is that you Mo-Dean?"

Benham has already provided around £25 million of funding for the new stadium, though the final cost could rise to £45 million to overcome all the challenges. In particular, the site is surrounded by three railway lines, which poses “unique problems”, including the construction of a bridge across one of the lines.

This is another sign of the owner’s commitment, though the delays have been frustrating for Benham: “When I first became involved with the club, around ten years ago, we were talking about the new stadium possibly being used as a venue for the 2012 Olympics, but it has drifted further and further away.” Nevertheless, the club “remains confident of being in the new stadium ready for the 2018/19 season.”

Once again, despite rising 44% to £2.4 million, Brentford’s commercial income was also among the smallest in the Championship, way behind Norwich City £12.8 million, Leeds United £11.3 million and Brighton £8.9 million. In fact, it was only higher than Millwall £1.9 million and Wigan £1.5 million.

Brentford’s shirt sponsor is Matchbook, the global sports betting exchange and one of Benham’s companies. The deal was extended for the 2015/16 season with an option to extend for one more year. The partnership also sees Matchbook branding on the roof of the New Road Stand.

In 2014 Adidas extended the kit supplier deal by four years until the end of the 2018/19 season.

Brentford’s wage bill shot up by 78% (£8 million) from £10 million to £18 million in 2014/15, though this was impacted by bonuses for finishing in the play-off positions. Effectively, Brentford have increased their wage bill in order to get out of League Two and League One, and then upped it again in the Championship.

This has resulted in a fairly horrific wages to turnover ratio of 178%, though this was actually better than the 224% in League One.

Of course, wages to turnover invariably looks terrible in the Championship with no fewer than 10 clubs “boasting” a ratio above 100%, but Brentford’s 178% was only surpassed by Bournemouth 237% - and that was inflated by substantial promotion bonus payments.

However, Brentford’s £18 million wage bill was still in the lower half of the Championship. On the fairly safe assumption that Bolton’s wage bill was higher than Brentford’s, the Bees only had the 15th highest wages in 2014/15.

Of course, this was still ahead of many other clubs, which might surprise some Brentford fans, as Benham noted, “The big myth of last season was the squad was run on a shoestring. In reality, the total first team budget was mid-table.”

That said, Brentford will always struggle to keep its top talent, as there are some clubs that will pay players a lot more. The impact of parachute payments is again felt keenly here with the highest wage bills found at Norwich City £51 million, Cardiff City £42 million, Fulham £37 million and Reading £33 million.

Benham appreciates this point: “It comes back to budget. Once we went up, and the players became aware that if they were playing for any of our Championship rivals, they would get paid more money, we had a job on our hands keeping certain players happy. Our structure is much more bonus-heavy, which hasn’t helped us.”

This is likely to mean a fairly frequent turnover of players, as those departing will need to be replaced by new recruits, who, if they do well, will almost inevitably be sold. Many clubs have to follow this strategy, but it’s a difficult one to successfully execute.

Another aspect of player costs that has risen is player amortisation, which is the method that most football clubs use to expense transfer fees and was adopted by Brentford this season. This has grown by £1.8 million from £0.3 million to £2.1 million in 2015.

As a reminder of how this works, transfer fees are not fully expensed in the year a player is purchased, but the cost is written-off evenly over the length of the player’s contract via player amortisation. As an illustration, if Brentford were to pay £5 million for a new player with a five-year contract, the annual expense would only be £1 million (£5 million divided by 5 years) in player amortisation (on top of wages).

Brentford’s £2.1 million is towards the lower end of the Championship, significantly surpassed by most other clubs, especially those relegated from the Premier League in recent times, i.e. Norwich City, Cardiff City and Fulham. Of course, this expense will have grown considerably in 2015/16 based on the much high transfer expenditure recently.

For many years, Brentford spent hardly anything on player recruitment, but have averaged gross spend of around £5 million in the last two seasons. This season alone included the following purchases: Andreas Bjelland (FC Twente) £2 million, Lasse Vibe (IFK Göteborg) £1 million, Maxime Colin (Anderlecht) £0.9 million and Josh McEachran (Chelsea) £0.8 million.

However, as a result of the high player departures, Brentford actually had £12 million of net sales over the last two seasons. Benham argued that this was a necessity, “With FFP we were always going to have to sell players.” This meant that they were comfortably outspent by the likes of Derby County £29 million and Middlesbrough £23 million.

It’s a challenge to sign players, but Brentford can offer certain advantages, as Benham explained: “What we can demonstrate to potential new signings is that if they come to Brentford, and excel, then it can be a springboard for their careers. Look at what it did for Andre, Moses and Forshaw. When they come to a team like us, they also have more chance of getting regular first team football.”

Brentford have also made good use of the loan system, e.g. last season their loans included Sergi Canos from Liverpool, Marco Djuricin from Red Bull Salzburg and John Swift from Chelsea.

Brentford’s net debt more than doubled in 2015 from £19.2 million to £43.5 million, as gross debt rose by £23.8 million from £22.7 million to £46.4 million and cash fell £0.5 million from £3.5 million to £3.0 million.

Most of the debt (£43.4 million) is owed to the club’s owner, Matthew Benham, and is interest-free, though secured by a legal charge over the club’s freehold property. In addition, there are £2.9 million of other loans, while the club has a £500,000 overdraft facility.

Brentford’s was by no means the largest debt in the Championship, being lower than nine other clubs. In fact, four clubs had debt over £100 million, including Brighton £148 million, Cardiff City £116 million and Blackburn Rovers £104 million. Bolton Wanderers have not yet published their 2015 accounts, given their much-publicised problems, but their debt was a horrific £195 million in 2014.

That said, the vast majority of this debt is provided by owners and is interest-free, so the amounts paid out by Championship clubs in interest is a lot less than you might imagine.

Even after adding back non-cash items such as player amortisation and depreciation, then adjusting for working capital movements, Brentford have made substantial cash losses from operating activities, e.g. £10.8 million in 2015. They then spent a net £3.2 million on player recruitment and a hefty £16 million on infrastructure investment, i.e. stadium development. This was funded by £23.7 million of loans and £5.9 million of new share capital.

Since 2009 the club’s only real source of funds has been money pumped in by Matthew Benham. This has been used to cover operating losses (£30 million) with a further £24 million spent on infrastructure investment (stadium and training ground) and £8 million on acquiring a subsidiary (for the Lionel Road site). Only £4 million went on player purchases (net), made up of £8 million purchases and £4 million sales.

Benham’s total commitment was up to £76 million as at 30 June 2015, comprising £43 million of loans, £25 million of non-voting preference shares, £5 million of new share capital and £2 million of working capital loans. This included £24.5 million on the Brentford Community stadium.

With some justification, the chairman described this as “magnificent financial backing”, while even Mark Warburton, who has more reason than most to criticise the owner said, “You have to respect the fact that someone’s put so much money into the football club and put it into this state of health.”

Of course, the long-term aim would be to reduce this reliance on Benham. As far back as 2013, the chairman said, “We believe as a board we should be striving to be breaking even on a sustainable basis, without the requirement for substantial cash injections from our owner.”

Being so dependent on one individual can be a concern, but Benham has to date been willing to provide substantial funding. However, Brentford will not be able to simply buy success, as they will need to continue to comply with the Financial Fair Play regulations.

Under the rules for 2014/15, clubs were only allowed a maximum annual loss of £6 million (assuming that any losses in excess of £3 million were covered by shareholders injecting £3 million of capital). Any clubs that exceeded those losses were subject to a fine (if promoted – like Bournemouth) or a transfer embargo (if they remain in the Championship – as was the case with Fulham, Nottingham Forest and Bolton Wanderers).

It should be noted that FFP losses are not the same as the published accounts, as clubs are permitted to exclude some costs, such as youth development, community schemes, promotion-related bonuses and infrastructure investment (such as stadium improvements and training ground). This latter expense in particular will help Brentford’s FFP calculation, as they have spent a lot in these areas.

"Spanish Steps"

From the 2016/17 season the regulations will change to be more aligned with the Premier League, so that the losses will be calculated over a three-year period up to a maximum of £39 million, i.e. an annual average of £13 million. This will likely encourage clubs to “go for it” even more.

Recently the club announced that they would close their Academy, which has come as a major surprise, given that they had attained the coveted Category Two status. This is once again about finding an edge in order to compete and progress as a Championship football club, as Brentford “cannot outspend the vast majority of our competitors”, though it will undoubtedly hit the affected youngsters hard.

The club statement explained their decision thus, “This philosophy is particularly relevant with regards to the future of the Brentford FC Academy. As a London club, there is strong competition for the best young players, and the club’s pathways to First Team football must be sufficiently differentiated to attract the level of talent that can thrive in a team competing towards the top end of the Championship.”

“Moreover, the development of young players must make sense from a business perspective. The review has highlighted that, in a football environment where the biggest Premier League clubs seek to sign the best young players before they can graduate through an Academy system, the challenge of developing value through that system is extremely difficult.”

"Wild Woods"

There’s no doubt that Brentford have come a long way, but the club is still far from breaking even, so continues to be reliant on Matthew Benham to a large extent. The owner has invested heavily to give the club the best possible chance, but there is no guarantee of success, especially with big clubs like Newcastle United and Aston Villa joining the fray next season.

It will be important that the transfer budget is spent well in the summer. According to co-director of football, Phil Giles, there should be money available after the January sales: “The money will be reinvested in the summer. I believe we’re fine for FFP this season.”

Although Brentford is clearly a club with ambition, they have to strike the right balance off the pitch. A couple of years ago, Benham gave some idea of the long-term vision: “Every club in the Championship would like to get to the Premier League at some point, so we are no different. But we are not going to put a timeframe on it. At some point we are going to try to make a push for it... in x years. I don’t want to say publicly. But yes it is achievable within a few years.”

At the time that seemed extraordinarily bullish, though Bournemouth and Burnley have shown the way for “small” clubs. These days, the owner is keeping his feet on the ground: “Brentford is a long-term project, and we are a team in transition at the moment.”

In a recent interview, Benham beautifully summed up Brentford’s dilemma: “We will give it everything to go up – as long as it makes financial sense of course.”

********************************************************************************************************

Many of the Matthew Benham quotes in this blog have come from a rare, lengthy interview that the club’s owner granted to the excellent Brentford fan site Beesotted. You can read that interview in full here and also follow them on Twitter @beesotted and @billythebee99