Yet again Sunderland are involved in a fight against relegation, though they should be used to this annual struggle by now, as the last time they finished in the top half of the table was back in 2011 when they came 10th.

It is fair to say that the Black Cats have not exactly flourished under Irish-American owner Ellis Short, the billionaire financier who completed his takeover of the club in May 2009, replacing Niall Quinn as chairman two years later.

On the one hand, Short has proved himself a good owner by providing significant funding to Sunderland. In fact, not only has he loaned the club around £160 million interest-free, but he has actually capitalised £100 million of this debt. This is money he would only get back if he sold the club (and for a decent price).

On the other hand, Short has operated a flawed strategy, which has essentially amounted to a series of quick fixes, exacerbated by poor choices in player recruitment.

"Fast Khazri"

These pros and cons were acknowledged by the owner in a vigorous defence of his tenure: “The assertion that I have been unwilling to spend money to fulfil the ambitions of the club and its fans is completely wrong. Every penny that comes from TV money and other commercial activities is spent on operating the club – that is, buying players, wages, and other associated costs. I have never taken money out of the club. In fact, I have funded significant shortfalls each and every season.”

Short continued, “The amount that I fund, every season, exceeds the collective total amount funded by every owner the club has ever had since the club was formed in 1879. I have done this willingly because I want us to be more than a club that simply exists in the top flight. Negligible owner-funding during the Premier League era resulted in Sunderland not being in the top flight for 15 of the 22 years. Since I have been involved, the good news is that my investment has kept us in the Premier League for nine consecutive seasons.”

However, here’s the kicker: “The bad news is, for that amount of money spent, we should be better than we are and no-one knows that more than me. Has the money been spent effectively? No – that much is clear and ultimately that is my fault, but it is not a result of a lack of ambition or commitment.”

"Heroes and M'Vila"

Sunderland’s performance has not been helped by constant managerial upheaval. The club has had nine managers in the last ten years, including five in the last four years alone: Martin O’Neill, Paolo Di Canio, Gus Poyet, Dick Advocaat and Sam Allardyce.

The routine is all too familiar to Sunderland supporters: an initial positive impact under the new manager (or head coach), but when results take a turn for the worse, the manager is hastily given his P45. Rinse and repeat.

None of the managers has been given enough time to build their own team, leading to an imbalanced squad. The never-ending changes destroy any continuity, prevent any long-term planning and result in a confused, often contradictory, transfer strategy.

This is perhaps best seen in the disastrous big money purchases of Jozy Altidore, a striker who scored just once in 42 league games, and Jack Rodwell, who has hardly set the world alight since his £10 million signing.

"Where's Captain Kirkhoff?"

Short’s seeming inability to hire the right staff has also been displayed in the board room, as Margaret Byrne seemed to be out of her depth in the role of chief executive well before she had to resign following revelations about the timing and extent of her knowledge of Adam Johnson’s deeply inappropriate “relationship” with a 15-year-old girl.

At the beginning of the season the chairman ignored Advocaat’s please for a radical squad overhaul, which the Dutchman believed was essential if the club wanted to make progress. In fairness, he did splash out £15 million in the January transfer window, in order to bring in some fresh blood in the shape of Wahbi Khazri, Lamine Koné and Jan Kirchhoff. We shall soon see whether this has done the trick or whether it’s a case of “too little, too late”.

That said, history tells us that there is no guarantee that Sunderland would have bought well, even if they had “gone big” last summer. Indeed, recently they have effectively been spending to go backwards: 14th in 2013/14, 16th in 2014/15 and 17th or 18th this season.

Sunderland’s results off the pitch have been every bit as terrible as those achieved on the pitch, as seen in the 2014/15 figures. The loss increased by £8 million (49%) from £17 million to £25 million, primarily due to the wage bill soaring by £8 million (11%) to £77 million.

Revenue fell by £3 million (3%) from £104 million to £101 million with gate receipts decreasing by £4 million (26%) from £15 million to £11 million, mainly due to no repeat of the previous season’s cup run to the Capital One final. Broadcasting revenue was also down £3 million (4%) at £72 million following the lower finishing position in the Premier League. This was partly compensated by commercial income rising by £3 million (18%) from £18 million to £21 million.

It should be noted that Sunderland have changed the way that they classified revenue this year, including a restatement of the 2014 results. This has no net impact, but means that the figures reported for gate receipts in 2014 have reduced by £1.1 million, while commercial income has increased by the equivalent amount, specifically in conference, banqueting and catering.

Interest payable shot up by £3.7 million from £2.3 million to £6.0 million following a major change to the club’s borrowing arrangements with Security Benefit Corporation (SBC) replacing the previous bank loan and overdraft.

Player amortisation decreased by £3 million (10%) from £27 million to £24 million, while there was a £3 million improvement due to the club booking an impairment charge (reduction in player values) the previous season.

Sunderland’s £25 million loss is the third largest in the Premier League for 2014/15, only behind QPR £46 million and Aston Villa £28 million. So what, you might say, don’t all football clubs lose money?

Not any more. Although football clubs have traditionally made losses, the increasing TV deals allied with Financial Fair Play (FFP) mean that the Premier League these days is a largely profitable environment. In fact, just six clubs lost money in 2014/15 and two of those (Manchester United and Everton) only lost £4 million.

In stark contrast to Sunderland, their north-east neighbours Newcastle registered a £36 million profit, while Leicester City made £26 million – the season before they won the title. It really is some kind of a special “achievement” for Sunderland to lose so much money in today’s Premier League.

Of course, this is nothing new for Sunderland, as the last time that the club made a profit was way back in 2006. Since then they have lost money for nine consecutive seasons, accumulating total losses before tax of £170 million in this period, averaging £19 million a year.

Not only that, but the deficits have worsened over the last three seasons , increasing from £13 million in 2013 to £17 million in 2014, then again to £25 million in 2015. In fairness, these are not so bad as the £32 million loss posted in 2012, but that’s not really much to write home about.

If Sunderland were making losses while improving the squad, that would at least be understandable, but losing money while the team is getting worse is an awful combination.

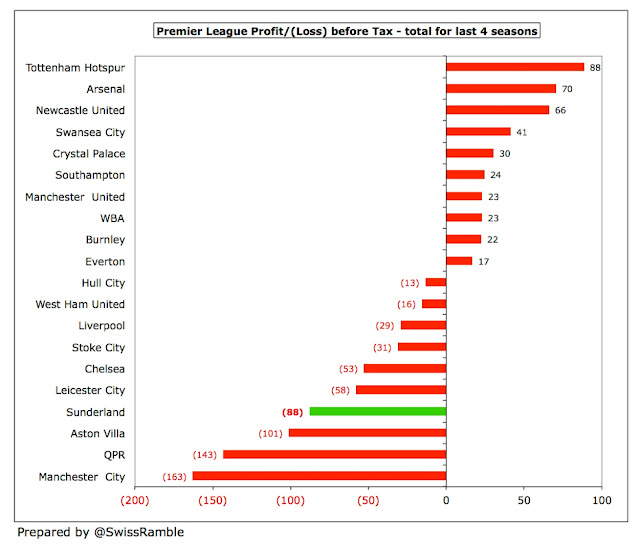

This unwanted consistency is reflected in Sunderland having the fourth highest loss (£88 million) in the Premier League over the last four years, only behind big-spending Manchester City £163 million and those well-known financial basket cases QPR £143 million and Aston Villa £101 million.

Furthermore, Sunderland is one of only three clubs to have reported losses in each of the last four seasons. The other members of this unholy trinity were, of course, QPR and Villa.

Profit from player sales can have a major influence on a football club’s bottom line, as best shown in 2014/15 by Liverpool, whose numbers were boosted by £56 million from this activity, largely due to the sale of Luis Suarez to Barcelona.

Sunderland reported less than £4 million here, £1 million below the previous season, though this was actually better than eight other Premier League clubs.

However, Sunderland have only made £38 million from player sales in the last nine seasons, including a £3 million loss in 2012. Two years have bucked the trend: (a) 2011- £26 million from selling Jordan Henderson to Liverpool, Darren Bent to Aston Villa and Kenwyne Jones to Stoke City; b) 2013 - £11 million from selling Simon Mignolet to Liverpool and Ahmed Elmohamady to Hull City.

This helps explains why the reported losses were “only” £8 million in 2011 and £13 million in 2013. Excluding player sales, the losses those years were every bit as bad as the other years.

Former chief executive Margaret Byrne outlined the club’s thinking on player sales a couple of years ago: “We’ll be reporting another big loss this year. We don’t want to do that, but we’ve taken a decision not to sell our best players. We had lots of offers in the summer that would certainly have put us in a much better position, but Ellis said that we’re not selling them. Of course you could be a profitable club and sell your best players, but it’s a relegation model. We want to keep our assets and not sell them.”

Another way of looking at this is that Sunderland have not really had any players that other clubs would be interested in buying, at least for decent money, though next year’s accounts will include the profitable sale of Connor Wickham to Crystal Palace for around £7 million.

To get an idea of underlying profitability, football clubs often look at EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Depreciation and Amortisation), as this strips out player trading and non-cash items. This has actually not been too bad at Sunderland, as the club has been basically breaking even or better in the last few seasons, though it did fall from £13 million to £4 million in 2015.

However, everything is relative, the point here being that Sunderland’s EBITDA is one of the lowest in the top flight, only ahead of Swansea City, Aston Villa and QPR. To place it into perspective, Newcastle United’s EBITDA was over ten times as high at £43 million.

One of Sunderland’s fundamental problems is a lack of revenue growth – except for the centrally negotiated Premier League television deals. In fact, Sunderland’s revenue has decreased in three of the last four seasons (2012, 2103 and 2015).

Since the club’s first season back in the Premier League in 2007/08, revenue has increased by £37 million (59%), but almost all of that (£33 million) has come from new TV deals, hence the rises in 2011 and 2014. In the same period, commercial income has only grown by £7 million (albeit representing a 48% rise), while gate receipts have actually fallen by £3 million (21%).

Sunderland’s under-performance in 2014/15 is particularly telling, as they are one of only six Premier League clubs whose revenue fell last season: their 3% decline was only “beaten” by Manchester United, but the Red Devils’ decrease was driven by the absence of European competition. Granted, there is less chance for clubs to massively grow revenue in the second year of a TV deal, but it is obviously disappointing when revenue actually falls.

Following this decrease in 2014/15, Sunderland’s revenue of £101 million was the 15th highest in the Premier League, only ahead of Stoke City £100 million, WBA £96 million and the three clubs relegated that season (QPR £86 million, Hull City £84 million and Burnley £79 million).

Clearly, Sunderland are miles behind those clubs that Big Sam affectionately refers to as the “big boys”: Manchester United £395 million, Manchester City £352 million, Arsenal £329 million, Chelsea £314 million and Liverpool £298 million. That said, you only have to look at Leicester City (£104 million) to see what can be achieved with low revenue.

Perhaps surprisingly, Sunderland’s revenue is the 25th highest in the world according to the annual Money League. As Deloitte observed, “This is again testament to the phenomenal broadcast success of the English Premier League and the relative equality of its distributions, giving its non-Champions League clubs particularly a considerable advantage internationally.”

That’s obviously a fine accomplishment, but it does not really help Sunderland much domestically, as no fewer than 17 Premier League clubs feature in the top 30 clubs worldwide by revenue.

Even so, Sunderland generate more revenue than famous clubs like Napoli, Valencia, Sevilla, Hamburg, Stuttgart, Lazio, Fiorentina, Marseille, Lyon, Ajax, PSV Eindhoven, Porto, Benfica and Celtic. Yes, that list includes Sevilla, who have just qualified for their third consecutive Europa League final, having won the last two editions.

All that lovely Premier League money means that 68% of Sunderland’s revenue comes from broadcasting, though this is slightly lower than the previous season (69%). Commercial income’s share has risen from 17% to 21%, while match day is down from 14% to 11%.

This revenue mix might sound concerning, but it is fairly common in the Premier League. For example, in 2014/15 nine clubs in the top flight were dependent on TV for more than 70% of their revenue, with four clubs earning at least 80% of their revenue from broadcasting, namely Burnley, Swansea City, Hull City and West Brom.

Sunderland’s share of the Premier League television money fell by £2 million from £72 million to £70 million in 2014/15, partly due to smaller merit payments for finishing two places lower in the league, and partly due to only being shown live on TV 11 times (compared to 13 the previous season), which reduced the facility fee.

The Premier League deal is the most equitable in Europe with all other elements distributed equally (the remaining 50% of the domestic deal, 100% of the overseas deals and central commercial revenue), but poor performance can still adversely impact a club’s revenue.

For example, if Sunderland had maintained their 10th place finish in the four seasons since 2010/11, they would have pocketed an additional £21 million. This highlights the tricky balance between controlling expenditure and investing for success. Spending money is obviously not a guarantee, but a safety first approach can end up leaving cash on the table.

Note: the broadcasting revenue of £69.1 million in Sunderland’s accounts is lower than the £69.9 million distribution advised by the Premier League. One possible explanation for this discrepancy is that Sunderland might have included the £4.4 million of Premier league commercial revenue in commercial income, even though most other clubs classify it as broadcasting income. Incidentally, this would also account for some of the reported growth in commercial income.

"Cool for Cattermole"

Clearly, Sunderland’s big fear is that they will be relegated and therefore miss out on the huge TV distributions. As Ellis Short noted in the accounts: “The directors consider the major risk of the business to be a significant period of absence from the Premier League.”

There is never really a good time to be relegated, but this is definitely one season where clubs want to avoid the dreaded drop, as the TV money goes stratospheric in 2016/17. My estimates suggest that Sunderland’s 16th place would be worth an additional £31 million under the new contract, taking their annual payment up to an incredible £101 million. This is based on the contracted 70% increase in the domestic deal and an assumed 30% increase in the overseas deals (though this might be a bit conservative, given some of the deals announced to date).

This assessment was reinforced by Allardyce: “It’s about protecting Premier League status, because, if the club wants to move forward, it can’t have the financial devastation relegation will bring. It needs the pot of money the new television deal will bring in the summer.”

Even though Sunderland would be protected to some extent by the £25 million parachute payment that is added to the £1.9 million given to all Championship clubs from the Football League’s own TV deal, they would still have to contend with a £43 million cut in TV money if relegated.

Obviously, this would be considerably higher than those Championship clubs without parachute payments, who only receive £5 million, including a solidarity payment from the Premier League of £2.3 million.

This disparity will become absolutely colossal once the new 2016/17 TV deal kicks in, e.g. around £63 million, even after an increase in the parachute payments. That’s a significant reduction to absorb, even if players have relegation clauses in their contract (there are conflicting reports in the media about whether that is the case at Sunderland).

As noted above, from 2016/17 parachute payments will be higher, though clubs will only receive these for three seasons after relegation. My estimate is £75 million, based on the percentages advised by the Premier League (year 1 – £35 million, year 2 – £28 million and year 3 – £11 million). Up to now, these have been worth £65 million over four years: year 1 – £25 million, year 2 – £20 million and £10 million in each of years 3 and 4.

Gate receipts were down by 26% (£3.8 million) from £14.6 million to £10.8 million, largely due to five fewer home matches, as there were good cup runs in both domestic competitions the previous season with Sunderland reaching the final of the Capital One Cup and the quarter-finals of the FA Cup. In addition, season ticket prices were cut for the 2014/15 season.

This places Sunderland in the lower half of the Premier League table when it comes to match day income and is significantly less than the elite clubs, e.g. Arsenal earn £100 million here (or more than nine times as much as Sunderland).

Realistically, this is always going to be the case, as Sunderland’s ability to charge higher ticket prices and earn from corporate hospitality is far lower than major clubs. As Byrne said, “You have to look at the area. A restaurant in London is more expensive than a restaurant in Sunderland.”

Indeed, season ticket prices were frozen for the 2015/16 season and reduced for 2016/17 with adult season tickets starting at £350 (which averages £18 a game) and the most expensive just £475.

Byrne explained, “Keeping the cost of watching football at a realistic level is something that is very topical at present, but for us it has always been top of our agenda. We know that the fans are what make this football club great and we hope that as many fans as possible will continue to have the opportunity to come to games and support the team.”

Sunderland’s fans have indeed kept the faith, as their average attendance of over 43,000 (up 2,000 in 2014/15) was the 6th highest in the Premier League, ahead of clubs like Chelsea, Everton and Tottenham.

In fact, average attendances have actually risen three years in a row from 39,000 in 2011/12, which is an incredible statistic considering the quality of football on display. As former manager Roy Keane observed, “Sunderland is a brilliant football club and there are some of the best supporters in the world up there.”

Sunderland’s commercial income rose by 18% (£3.3 million) from £17.9 million to £21.2 million, comprising £10.2 million sponsorship and royalties, £9.2 million conference, banqueting and catering, £0.8 million retail and merchandising and £1.0m other.

That was the 11h highest in the Premier League, just behind West Ham £22 million and Newcastle United £25 million. Clearly, it is significantly lower than the top six clubs: Manchester United £197 million (around ten times as much as Sunderland), Manchester City £173 million, Liverpool £116 million, Chelsea £108 million, Arsenal £103 million and Tottenham £60 million.

The disparity is most evident when comparing the shirt sponsorship deals. In 2014/15 Sunderland had a deal with Bidvest, one of the largest food services companies in the world, which was worth £5 million a year. This has been replaced with a two-year deal with Dafabet, an eGaming operator, also for £5 million a season. This looks very low compared to the major clubs, e.g. Manchester United have a £47 million with Chevrolet and Chelsea £40 million with Yokohama Rubber.

It’s a similar story with Sunderland’s kit supplier, Adidas. Although this deal is a long-term partnership, extended until the summer of 2020, it’s unlikely to be worth more than £1-2 million a season, compared to, say, Manchester United’s Adidas deal, which will be worth an astonishing £75 million a year from the 2015/16 season.

In fairness, most clubs outside of the absolute elite have struggled to secure such massive deals and Sunderland would have to enjoy a sustained run of success to substantially improve their commercial agreements.

Sunderland’s wage bill rose 11% (£7.6 million) from £69.5 million to £77.1 million in 2014/15 on the back of a rise in full-time headcount from 272 to 287 (players and scholars down 3 from 68 to 65, other employees up 18 from 204 to 222).

It is not known for certain whether this also includes a severance payment to Gus Poyet, who was sacked in March 2015 (or indeed to Paolo Di Canio the previous season), but this factor has presumably also inflated the reported wage bill.

It is equally unclear how much Sunderland are contributing to the salaries of the numerous players they have out on loan, e.g. Liam Bridcutt at Leeds United, Steven Fletcher at Marseille, Danny Graham at Blackburn Rovers, Sebastian Coates at Sporting and Will Buckley at Birmingham City.

The important wages to turnover ratio increased from 67% to 76%, which is the second highest (worst) in the Premier League, only behind QPR. This highlights how out of control the wage bill has been at Sunderland. For some context, high-flying Leicester’s ratio was 55%.

Furthermore Sunderland’s wage bill of £77 million was the ninth highest in the top tier, ahead of clubs like West ham £73 million, Southampton £72 million and, yes, Leicester City £57 million, so it’s fair to say that the club has massively under-performed against its expenditure.

Evidently, Sunderland’s wages are significantly lower than the likes of Chelsea £216 million, Manchester United £203 million, Manchester City £194 million and Arsenal £192 million, but they should be enough for them to be in a comfortable mid-table position, as opposed to being involved in a relegation battle.

All that being said, Sunderland’s 11% wages growth in 2014/15 was by no means one of the largest in the Premier League with no fewer than 10 clubs reporting higher percentage increases.

In line with the overall wage increase, the highest paid director, presumably Margaret Byrne, saw her remuneration jump 10% from £663k to £726k. As a local comparison, Lee Charnley only earned £150k at Newcastle.

The wage bills of the mid-ranking clubs seem to be converging around the £70 million level: West Ham £73 million, Southampton £72 million, Swansea £71 million, WBA £70 million, Crystal Palace £68 million, Stoke City £67 million and Newcastle £65 million. However, Sunderland’s wage bill was a touch higher at £77 million, though they have not really made the best use of their additional funds.

Another aspect of player costs that has had a disproportionate impact on Sunderland’s bottom line is player amortisation, which is the method that football clubs use to account for transfer fees. Sunderland have spent a fair bit of money bringing players into the club, which has been reflected in player amortisation rising from just £2 million in 2006 to £24 million in 2015 (though this was £3 million lower than the previous season).

As a reminder of how this works, transfer fees are not fully expensed in the year a player is purchased, but the cost is written-off evenly over the length of the player’s contract via player amortisation. As an illustration, if Sunderland were to pay £10 million for a new player with a five-year contract, the annual expense would only be £2 million (£10 million divided by 5 years) in player amortisation (on top of wages).

Not only is player amortisation a sizeable element (20%) of Sunderland’s total expenses of £124 million, but it is also the 8th highest in the Premier League, only surpassed by the really big spenders, e.g. Manchester United’s player amortisation is around four times as much, with the massive outlay under Moyes and van Gaal driving their annual expense up to £100 million.

Since they returned to the Premier League in 2007, it feels like there have been three distinct phases in Sunderland’s transfer activity: initially there was substantial average net spend of £24 million in the first 3 seasons in order to strengthen the squad; then the taps were partly turned off with average net sales of £4 million in the next two seasons; finally a lot of money was needed to fund the plans of four different managers with average net spend of £18 million in the last four seasons.

This recent spending is described by the club as “significant investment in the playing squad” in the accounts and it does indeed compare favourably to other Premier League clubs in the same period. Obviously, it is far below the money shelled out by the elite clubs, but it is actually the 8th highest net spend over the last four seasons.

No, Sunderland’s basic problem is they have bought badly with a vast quantity of bang average players arriving for inflated fees. Don’t take my word for it, but listen to the last two managers. First up, Dick Advocaat: “The last five years have not been so great,” said Advocaat. “We bought players who the club is still paying (transfer fee installments and wages) and they are not even here anymore. There have been a lot of mistakes here in the past.”

Big Sam has been singing from the same song sheet: “Going forward, we need to spend the money very wisely. That is my responsibility with Ellis, when we stay in the Premier League, to say ‘We will not waste money, as it has been wasted by past managers’.”

Gross debt has risen by £47 million from £94 million to £141 million. The amount owed to Ellis Short (via his company Drumaville Limited) has increased from £28 million to £58 million, but the majority of the debt is external with £83 million owed to Security Bank Corporation (SBC), owned by Guggenheim Partners, including a £68 million loan and a £15 million revolving credit facility.

The loan is long-term, expiring on 27 August 2019, and carries an interest rate of 7.5% plus LIBOR. This is a fairly high interest rate, which is a good indication of what lenders think of Sunderland’s financial status. It is also higher than the previous bank loan (LIBOR plus 3%).

In fact, Sunderland’s net interest payable of £6 million was the third highest in the Premier League in 2014/15, only surpassed by Manchester United and Arsenal. In stark contrast, Newcastle United had zero interest payments, as all their debt is owed to Mike Ashley and is interest-free.

Debt has almost tripled from £48 million in 2009 and this is a sizeable burden for a football club of Sunderland’s size, so it is likely that much of the extra TV money will be used to reduce this to a more manageable level. This was more or less confirmed by Byrne: “This TV deal gives the club a chance to get our books in order.”

Incredibly, the debt would have been even higher at £242 million if the shareholders had not converted £101 million into equity over the last few years.

In addition, the net amount owed on transfer fees to other football clubs has more than doubled from £8 million to £18 million, while the contingent liabilities (potential payments that depend on number of appearances, surviving in Premier League, etc) have also increased from £8 million to £12 million – though the club states that “some of these are extremely remote”.

Only three Premier League clubs had more debt than Sunderland in 2014/15: Manchester United, who still have £444 million of borrowings even after all the Glazers’ various re-financings; Arsenal, whose £232 million debt effectively comprises the “mortgage” on the Emirates stadium; and QPR £194 million, though the West London club have recently converted £181 million into capital.

The accounts also refer to a legal case that might require the club to pay £7.6 million. This presumably refers to the Ricky Alvarez saga, where the midfielder was signed on loan with a purchase clause if Sunderland avoided relegation. Although this obviously happened, the club argued that the agreement was invalid, as Inter, his owners, had refused to allow the player to undergo knee surgery. Sunderland’s lawyers believe the club has a strong case, but there are rumours that FIFA will find against them.

Even though Sunderland make hefty operating losses, these are brought into line once non-cash items like player amortisation and depreciation are added back. However, that still does not provide enough surplus funds, so the club continues to require financing from either the bank or the owner if it wishes to spend reasonable sums on player investment.

As Margaret Byrne put it: “Because we’re not producing profits, every time we buy a player, Ellis (Short) is virtually buying that player for the club himself. We’re really lucky to have his backing and support.”

Interestingly, £20 million of the SBC loan has been classified as an investment, representing cash held as security in relation to the facility with SBC.

Since 2007 Sunderland has had £241 million cash available to spend, but almost all of this has come from increasing debt, £159 million from the owners and £59 million from the bank, with only £23 million generated from operating activities.

Over 70% of this (£173 million) was spent on player purchases (net), £24 million on interest payments, £20 million on investments and £11 million on infrastructure investment. The remaining £13 million simply increased the cash balance.

The big question at Sunderland is how long will Ellis Short be willing to bankroll the club?

The accounts state that the owner is willing and able to continue to support the club’s operations “for the foreseeable future”, while Short himself spoke of his vision for Sunderland: “No-one who knows me or knows anything about me would say that I have no ambition for the club. That ambition certainly has not been realised yet, but it does not mean that I don’t have it.”

"Life through a Lens"

As we have seen, the reliance on Short has been somewhat reduced, but only by the club taking on expensive debt with Security Benefit Corporation. Intriguingly, the terms of their loan include warrants that entitle SBC to purchase a minority interest in Sunderland’s share capital. Some have taken this as the first sign that Short might be seeking a way out, though this has been privately denied.

In any case, it is not that easy to sell a football club that is facing the threat of relegation, as Short’s compatriot Randy Lerner has found to his cost at Aston Villa.

Much is hanging on the club managing to avoid the drop, not least the future of Sam Allardyce. Although he has a contract running until 2017, he has hinted that his future at Sunderland depends on them surviving in the Premier League.

If the club does succeed, then they will have to change their strategy. There is no need to go crazy; they simply have to keep faith with the manager and provide him with a reasonable budget. It would then be up to Allardyce to spend the money shrewdly, if Sunderland want to achieve more than Premier League survival.

If the club does succeed, then they will have to change their strategy. There is no need to go crazy; they simply have to keep faith with the manager and provide him with a reasonable budget. It would then be up to Allardyce to spend the money shrewdly, if Sunderland want to achieve more than Premier League survival.

0 comments:

Post a Comment