Wolves finished the 2015/16 Championship in an uninspiring 14th position, which was particularly disappointing for the grand old Midlands club, as they had only just missed out on a play-off place on goal difference the previous season.

That view was confirmed by chief executive Jez Moxey, who described the season as “very challenging”. He added, “we’re frustrated, we’re angry, and it’s not okay – it’s not good enough for Wolverhampton Wanderers.”

Much of the supporters’ criticism for this sad state of affairs has been directed at the owner, Steve Morgan, whose tenure has seen an amazing rollercoaster ride. Morgan, who made his fortune as the founder of house builder Redrow, purchased the club in August 2007 for a nominal £10 fee from Sir Jack Hayward, though he also had to pledge a guaranteed £30 million investment.

This funding helped Wolves gain promotion two years later to the Premier League, where they spent three seasons before suffering two successive relegations to League One, though they did return to the Championship at the first attempt with a record points total.

"Irish heartbeat"

Wolves stay in the Premier League was characterised by financial prudence, as shown by regular profits, low wages, no debt and high cash balances. Nothing wrong with a sensible financial strategy, of course, but in the unforgiving world of modern football, where money talks loudest, it was also a gamble that ultimately failed to pay off, leading to the club falling into what Moxey called a “tailspin”.

Wolves’ prospects were not helped by some bizarre recruitment decisions. First, Mick McCarthy, a manager who had seemed completely in tune with the Morgan/Moxey ethos, was dismissed after a poor run of form, only to be replaced by his inexperienced assistant Terry Connor, who failed to prevent relegation to the Championship.

Wolves then hired the Norwegian Stale Solbakken, who might have been an imaginative choice, but the poor results continued, so his reign lasted only six months. His replacement was former Welsh international Dean Saunders, who saw his side relegated to the third tier for the first time since 1985, whereupon his contract was terminated.

Finally, a safe pair of hands was secured in the shape of Kenny Jackett, who has been head coach since May 2013, and succeeded in guiding Wolves back to the Championship.

"God put a smile on my face"

In fairness to Morgan, he did set out his stall early doors after he made the investment into the club, “Although this is a significant amount of money, there will not be an ‘open cheque book’ approach to signing players. Instead the club will build on the current strategy of steadily and progressively developing a team of young, hungry and talented players.”

Financial stability has been the mantra with Morgan lecturing others on their cavalier approach: “We have tried to manage this as a proper business and I wish other clubs would do the same.” That’s all well and good, but many fans have wondered whether things would have gone differently if the club had made more use of its “very healthy financial position” when in the top flight. Ironically, some of the subjects of Morgan’s scorn are still in the Premier League and are now coining it from the ever-increasing TV deals.

Similarly, the lack of investment in the playing squad last summer meant that Wolves did not maintain the momentum built up over the past two seasons and left them languishing in the lower half of the Championship.

"Dominic dancing"

Moxey has said that the club’s priority is to get back to the Premier League, then “recharge the finances of the business and stay in there”, but very few clubs are capable of doing this without pushing the boat out a little. It’s true to say that Burnley have managed to achieve this feat, but they are the exception to the rule.

Instead, Wolves have focused on the development of their “young players, who are seen as the future lifeblood of the club.” This can work from two perspectives: either the players can make valuable contributions to the first team squad; or they can improve the bank balance if sold to others for good money.

This is an admirable approach, but one that is tough to execute well in the intensely competitive Championship, which is a natural domain for hard-bitten, old professionals.

It also seems unlikely that Wolves will “go for it” next season, given that Morgan put his 100% shareholding in the club up for sale last September. Although he was keen to observe that his “ongoing commitment and financial support to Wolves” would continue until a new owner is found, it is difficult to see him funding a big outlay in the transfer market.

Wolves’ desire to balance the books was once again seen in their 2014/15 accounts, which registered a £0.7 million profit, though this was £7.8 million lower than the previous season’s £8.5 million profit, largely due to a £6.2 million (19%) reduction in revenue from £32.6 million to £26.4 million.

The main driver was a £9 million reduction in the parachute payments from the Premier League, though this was partially offset by a £1 million increase in the distributions from the Football League following promotion to the Championship, so there was a net £7.6 million (37%) fall in broadcasting income from £20.6 million to £13.0 million.

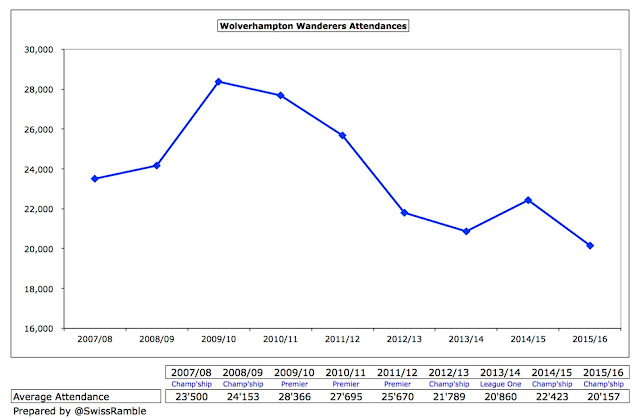

The promotion impact was also seen in gains in the other revenue streams: (a) commercial income increased by £1.0 million (16%) to £7.8 million, mainly due to sponsorship and advertising; (b) gate receipts were £0.4 million (7%) higher at £5.6 million, as attendances climbed from 20,860 to 22,423. However, profit from player sales fell by £1.3 million (35%) to £2.5 million.

The wage bill rose £1.3 million (8%) from £16.4 million to £17.7 million, but other expenses were £0.9 million lower at £7.3 million. The impact of exceptional items was one again felt, as there was no impairment of player registrations (£1.0 million in the previous season), but this was largely offset by restructuring credits, which were £0.6 million lower.

The accounts for the last three years have been majorly impacted by the £27.5 million restructuring provision that was booked in 2012/13 following the two consecutive relegations, comprising £15 million for onerous player contracts that were signed when the club was competing in higher divisions and £12.5 million player impairment values.

CFO Rita Purewal explained, “The restructuring was paramount and was an important part of our financial planning. We couldn’t carry those costs going forward.” Moxey was at pains to note, “This is not a cash loss, but includes necessary provisions to reflect the position we find ourselves in.”

He added, “This draws a line in the sand under the past”. In other words, the club decided to deal with the issue in one year rather than drip-feeding it over several years, which is fairly standard business practice.

However, it has clearly distorted the financial results, e.g. the 2014/15 reported profit of £0.7 million would have been a £5.9 million loss without the provision release of £6.7 million. Similarly, the 2013/14 profit of £8.5 million would have been a £1.7 million loss without a £10.2 million provision release. On the other hand, the massive £33.1 million loss in 2012/13 would have been only £5.6 million if the restructuring provision had not been created.

Note: for 2013/14 I have taken the figure of a £10.2 million provision release stated on Wolves’ website, even though it is not immediately clear from the accounts how this is calculated. The club has not yet responded to my request for clarification.

Where we do agree is that £2.7 million of the provision was left on the balance sheet as at 31 May 2015, though the accounts expected that this would be fully utilised in the next year, i.e. benefiting the 2015/16 accounts.

Wolves were one of only six profitable clubs in the Championship in 2014/15, but almost all of these are due to special factors. As we have seen, Wolves £1 million was boosted by a £7 million provision release, but others also benefited from similar movements.

Ipswich Town were the most profitable with £5 million, but that included £12 million profit on player sales. Cardiff’s £4 million was boosted by £26 million credits from their owner writing-off some loans and accrued interest. Reading’s £3 million was largely due to an £11 million revaluation of land around their stadium. Birmingham City were helped by a £10 million parachute payment.

The only club to make money without the benefit of once-off positives was Rotherham United, who basically just broke even – and ended up avoiding relegation to League One by a single place.

However, the harsh reality is that the majority of Championship clubs lose money with four reporting losses above £15 million: Bournemouth £39 million, Fulham £27 million, Nottingham Forest £22 million and Blackburn Rovers £17 million. As Moxey wryly observed, “A lot of clubs spend a lot more than they can afford.”

This is clearly not the case at Wolves. That man Moxey again, “When Steve Morgan came in, he said… we would try to be self-sufficient.” Obviously, relegation from the Premier League has taken its toll with small underlying losses in the last three years (excluding the impact of the restructuring provision movements), but Wolves more than achieved their sustainability objective in the top flight.

In 2012 Wolves went down with a £2.2 million profit on their books, the same as the previous year, though even these were left in the shade by the hefty £9.1 million profit they made in 2010, their first year back.

In total, Wolves made £13.5 million of profit during their three seasons in the Premier League, which might not sound enormous these days, but was a rare accomplishment at the time. Fine, but the consequent relegations bring to mind the old saying, “Penny wise, pound foolish.”

Profit from player sales can have a major impact on a football club’s bottom line, but it’s not an enormous money-spinner outside the Premier League with the most profit made by Norwich City £14 million, followed by Ipswich £12 million, Leeds United £10 million and Cardiff City £10 million.

Wolves made less than £3 million from this activity in 2014/15, though this will increase to at least £10 million in the 2015/16 accounts, thanks to the sale of star striker Benik Afobe to Bournemouth for £10 million and player of the year Richard Stearman to Fulham for £2 million.

Moxey has previously indicated that the business plan includes selling some players to recoup some money, but this has obviously accelerated following relegation from the Premier League with £22 million profits in the last three seasons compared to just £8 million in the preceding three seasons.

Even though the chief executive claimed that the club did not need to sell its best players, it still raised “considerable sums” (£15 million) in the summer of 2012, mainly from selling Steven Fletcher to Sunderland, Matt Jarvis to West Ham and Michael Kightly to Stoke City.

To get an idea of underlying profitability, football clubs often look at EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Depreciation and Amortisation), as this strips out player trading and non-cash movements. It is therefore effectively cash profit-

This has been positive at Wolves in five of the last six years, albeit on a downward trend, falling from a peak of £21 million in the Premier League to £1 million in 2015, compared to £8 million in 2014 (the difference essentially being the lower parachute payment).

Most revealingly, Wolves generated a total of £53 million EBITDA during their time in the Premier League, some of which could surely have gone on improving a defence with the worst record in the division.

Some might think that £1 million of EBITDA is nothing to write home about, but to place this into context, only three Championship clubs had a positive EBITDA in 2014/15 (Birmingham City and Rotherham being the others) with Wolves having the highest. In stark contrast, in the Premier League only one club (QPR) reported a negative EBITDA, which is testament to the earning power in the top flight.

Wolves’ revenue in recent years has been essentially a tale of promotion and relegation. After they were promoted to the Premier League revenue in 2010 shot up by £42 million to £61 million, but relegation to the Championship saw revenue in 2013 fall by £29 million to £32 million, somewhat cushioned by a parachute payment of £16 million.

Surprisingly, revenue actually slightly rose to £33 million in League One, in 2014 though this was entirely due to the parachute payment increasing thanks to the new three-year broadcasting deal.

Annual revenue in 2015 was around £34 million (56%) lower than the last season in the Premier League (£39 million if you consider the peak revenue for each revenue stream from the time spent in the top flight). As well as lower TV money, there have also been steep reductions in gate receipts (30%), due to falling attendances, and commercial income (25%), due to reduced contractual sponsorship agreements in the lower leagues.

The importance of parachute payments is clear: in the three years up to 2015, Wolves received £45 million. The last payment was due in 2016 and was worth £10.5 million, giving a total of £56 million for the four-year cycle.

The lack of a parachute payment in 2016/17 will have a substantial, adverse impact on Wolves’ finances, as they will have to find £10 million from somewhere – either other revenue streams (unlikely), cost cuts or player sales.

That’s what makes Wolves’ limited assault on the Championship last season all the more perplexing. In 2014/15 they enjoyed the sixth highest revenue of £26 million, only behind Norwich City £52 million, Fulham £42 million, Cardiff City £40 million, Reading £35 million and Wigan Athletic £28 million. With that sort of firepower, a play-off place should be a legitimate aspiration.

Of course, these revenue figures are distorted by the parachute payments made to those clubs relegated from the Premier League, e.g. in 2014/15 this was worth £25 million in the first year of relegation.

However, if we were to exclude this disparity, Wolves would still be in a healthy seventh place and the revenue differentials would be smaller, albeit they would be behind different clubs, e.g. the top three would then be Norwich City £29 million, Leeds United £24 million and Brighton and Hove Albion £24 million.

Following the £9 million reduction in parachute payments in 2014/15, which Purewal described as “quite substantial”, broadcasting now only accounts for 49% of Wolves revenue (down from 63% the previous season). As a result, commercial’s share rose from 21% to 30% and match day increased from 16% to 21%.

In the Championship most clubs receive the same annual sum for TV, regardless of where they finish in the league, amounting to just £4 million of central distributions: £1.7 million from the Football League pool and a £2.3 million solidarity payment from the Premier League. Wolves secretary Richard Skirrow admitted, “Without the Sky deal, clubs would be in all sorts of turmoil.”

However, the clear importance of parachute payments is once again highlighted in this revenue stream, greatly influencing the top eight earners, though it should be noted that clubs receiving parachute payments do not also receive solidarity payments.

However, it should be noted that these payments are not a panacea, so Middlesbrough secured promotion last season, even though their broadcasting income of £6.2 million in 2014/15 was less than half of Wolves’ £13 million.

Looking at the television distributions in the top flight, the massive financial chasm between England’s top two leagues becomes evident with Premier League clubs receiving between £67 million and £101 million, compared to the £4 million in the Championship. In other words, it would take a Championship club more than 15 years to earn the same amount as the bottom placed club in the Premier League.

The size of the prize goes a long way towards explaining the loss-making behaviour of many Championship clubs. This is even more the case with the astonishing new TV deal that starts in 2016/17, which will be worth an additional £30-50 million a year, to each club depending on where they finish in the table.

As an example, I have (conservatively) estimated that the club finishing bottom in the Premier League next season will receive £92 million, which is £87 million more than a Championship club not receiving parachute payments. There is never a good time for a club to be relegated, but Wolves dropped out of the top flight at one of the worst times, as the Premier League has since seen two new blockbuster TV deals come in, and they now risk being left behind.

Moxey is painfully aware of this, but it does not sound like it will provoke a change in policy: “This illustrates the massive difference between being in the Premier League and being in the Championship. We will have to look at our strategy and think what we can do to improve our chances of promotion without going bankrupt. How much can you spend and be able to deal with that outlay if you still don’t get there? There has to be a semblance of sanity.”

From 2016/17 parachute payments will be higher, though clubs will only receive these for three seasons after relegation. My estimate is £75 million, based on the percentages advised by the Premier League (year 1 – £35 million, year 2 – £28 million and year 3 – £11 million). Up to now, these have been worth £65 million over four years: year 1 – £25 million, year 2 – £20 million and £10 million in each of years 3 and 4.

There are some arguments in favour of these payments, namely that it encourages clubs promoted to the Premier League to invest to compete, safe in the knowledge that if the worst happens and they do end up relegated at the end of the season, then there is a safety net. However, they do undoubtedly create a significant revenue disadvantage in the Championship for many clubs.

Despite rising 7% to £5.6 million, partly due to having one more home cup fixture, Wolves’ match day income was still in the bottom half of the table in the Championship. It was far lower than clubs like Norwich City £10.7 million, Brighton £9.8 million and Leeds United £8.8 million.

This was even though average attendances increased from 20,860 to 22,423 in 2014/15 with the sale of season tickets up 18% to 13,998, which meant that Wolves had the sixth largest crowds in the Championship, only behind Derby County, Norwich, Brighton, Leeds United and Nottingham Forest.

However, the 2014/15 increase was something of a blip, as Wolves’ attendances have been declining since relegation from the Premier League. In fact, attendances fell again by more than 2,000 to 20,157 in 2015/16. That meant that Wolves have lost more than 8,000 fans since the peak of 28,366 in 2009/10. That’s a lot of money left on the table right there.

It’s difficult to criticise the fans, who averaged more than 20,000 in League One, including the first 30,000 plus attendance since building an all-seater stadium in the early 90s. Nevertheless, the season ticket campaign for 2016/17 has seen a drop in sales, leading Moxey to admit, “We’re concerned about attendances, of course.”

The club has been pro-active in its pricing strategy, e.g. 2015/16 season tickets were held at the same level as the 2012/13 Championship season, while 2016/17 prices have again been frozen with reduced costs for children. The board stated, “We are fully aware of the financial challenges many supporters face in these difficult times and we are committed to helping fans to support the team with the most cost effective pricing policies for matches at Moline.”

Wolves “remain committed to a medium to long term redevelopment project for the Molineux stadium and its surrounding areas”, leading to a purchase of a nearby property in 2014/15 to create new parking spaces.

The club had already developed the Stan Cullis stand into two tiers for the 2012/13 season, raising capacity to 31,700, though the second stage, namely the rebuilding of the Steve Bull stand to increase capacity to 36,000, has been indefinitely postponed.

Although investment in a new stadium is usually a sound move, it is debatable whether it made sense for a club in Wolves’ position, when the money could have been used to strengthen the squad to give a better chance to return to the riches of the Premier League.

After rising 16% to £7.8 million, Wolves’ commercial income was among the largest in the Championship, only behind five clubs: Norwich City £12.8 million, Leeds United £11.3 million, Brighton £8.9 million, Watford £8.6 million and Derby County £8.5 million. This is perhaps more an indication of Wolves’ historical strengths, rather than their current status.

There has been some controversy about Money Shop, the new shirt sponsor from the 2016/17 season for a minimum of three years. Many are unhappy with the name of a payday lender being on the front of the famous old gold shirt, though the club has described this as a “significant commercial agreement”. This deal replaces Silverbug, a provider of IT services, that was worth “well over six figures”.

In March 2013 Wolves signed a four-year kit supplier deal with Puma until the end of the 2016/17 season. This is worth £1 million a season regardless of which division Wolves are in.

The wage bill rose by £1.3 million (8%) from £16.4 million to £17.7 million, though for an unexplained reason the prior year comparative has been restated from the £20.5 million included in the 2014 accounts. Either way, this is considerably lower than the £38 million wages in the Premier League. As Steve Morgan explained, “You have to cut the cloth when you go down.”

That has equally applied to the highest paid director, assumed to be Moxey, whose annual remuneration has fallen from £1.2 million to £0.5 million – though he has earned a total of £5.5 million in the last seven years, including £3.5 million in the halcyon days of the Premier League alone.

What is striking is how low the wages were in the top flight, as Moxey confirmed: “We stayed up for three years on a relatively small wage bill.” In fact, Wolves were demoted in 2012 with the 17th largest wage bill in the Premier League, so it was not a major surprise that they ended up in the relegation zone.

Over that three-year period, Wolves wages to turnover ratio averaged 57%, which is on the low side. That’s fine for clubs with high revenue like Manchester United and Arsenal, but not for clubs with Wolves’ revenue levels. However, just to prove that all that glitters is not gold, Wolves went down from the Championship with the fourth highest wage bill in the division.

In 2014/15 Wolves prudent approach was summed up by their 67% wages to turnover ratio, which was only higher than Rotherham United in the Championship. Invariably, wages to turnover looks terrible in this division with no fewer than 10 clubs “boasting” a ratio above 100%, including Bournemouth 237%, Brentford 178% and Nottingham Forest 170%, so Wolves’ ratio is strangely low.

In fact, Wolves’ wage bill of £18 million was only the 15th highest in the Championship, compared to having the 6th highest revenue. To place this into perspective, their Midlands rivals Nottingham Forest had a wage bill of £30 million (though admittedly they are not exactly the poster boy of football finances).

Moxey argued, “We’re trying to be smarter than the other clubs. We’re outperforming some of them and they are spending so much more than we are.”

Another way of looking at this is that Wolves had the second smallest wage bill of those clubs receiving parachute payments, though there is obviously a difference in the size of those payments depending on when a club was relegated.

The reduction in Wolves’ parachute payments is clearly a factor in the club’s thinking, as Purewal confirmed, “That’s why it was important to move on big earners who were no longer part of the plans.”

That challenge was exacerbated in League One, as there were no relegation clauses for demotion to that division. There had been 40% cuts after going down to the Championship, but few envisaged the second drop. That’s why the club had to discard the so-called “bomb squad”, i.e. under-performing players on chunky, long-term contracts such as Jamie O’Hara, Roger Johnson, Stephen Hunt and Kevin Foley.

In a similar way, the 2015/16 wage bill will benefit from the departure of high earners such as Bakary Sako, Richard Stearman and Sam Ricketts.

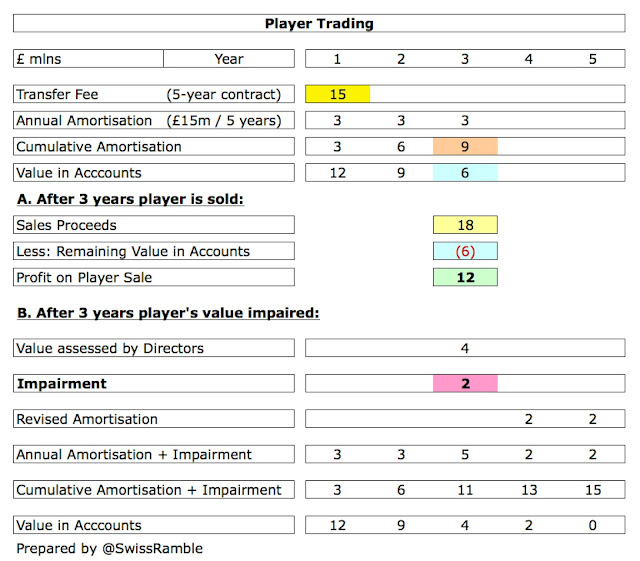

Another aspect of player costs that has decreased is player amortisation, which is the method that most football clubs use to expense transfer fees. This has fallen from the peak of £10.2 million in 2013 to £2.4 million in 2015.

As a reminder of how this works, transfer fees are not fully expensed in the year a player is purchased, but the cost is written-off evenly over the length of the player’s contract via player amortisation. As an illustration, if a club were to pay £15 million for a new player with a five-year contract, the annual expense would only be £3 million (£15 million divided by 5 years) in player amortisation (on top of wages).

However, Wolves’ financial results have also been influenced by the £13.6 million of impairment charges they have booked since 2013. This happens when the directors assess a player’s achievable sales price as less than the value in the accounts.

Going back to our example, if the player’s value were assessed as £4 million after 3 years instead of the £6 million in the accounts, then they would book an impairment charge of £2 million. Impairment could thus be considered as accelerated player amortisation. It also has the effect of reducing the annual player amortisation going forward.

As a result, Wolves’ £2.4 million is towards the lower end of the Championship, significantly surpassed by most other clubs, especially those relegated from the Premier League in recent times, i.e. Norwich City, Cardiff City and Fulham.

The other side of that coin is that player values on the balance sheet have also decreased, falling from £23.0 million in 2012 to £4.2 million in 2015. That is the accounting value in the books, but the actual market value would be much higher if Wolves were to sell any of its players.

This was explained by Purewal, who said that no value had been ascribed in the accounts to players who had progressed through the Academy, such as Dominic Iorfa, Danny Batth and Carl Ikeme, as no transfer fees had been paid.

Since Morgan bought the club, Wolves’ activity in the transfer market can be split into three distinct phases. First, little expenditure in the Championship; then a reasonable outlay in the Premier League when net spend averaged £12 million a season; finally, a return to net sales following relegation.

Moxey argued, “We have a massive net purchase of players under Steve Morgan because of his patronage”, but the figures do not really bear this out – unless you consider total net purchases of £10 million over this period to be “massive”.

The chief executive seemed to be nearer the mark earlier this year, when he admitted, "What we’re not doing is buying Premier League or top Championship players. We’re not in that position. That’s the reality. We have only a certain amount of money. Mostly, they came from Leagues One and Two.”

As a result of the sales of Afobe and Stearman, Wolves actually had £6 million of net sales over the last two seasons. This meant that they were comfortably outspent by the likes of Derby County £29 million, Middlesbrough £23 million and Burnley £14 million. In fact, the two automatically promoted clubs and the four that qualified for the play-offs filled six of the seven top places in the net spend league.

Incredibly, Wolves have been in the happy position of having net funds in seven of the last eight years. Basically, they have no financial debt, though their cash balance is now down to just £1 million compared to last year’s £7 million, having been as high as £26 million in 2011. It should be noted that they also owe other clubs £2 million in transfer fees.

Most Championship clubs carry a lot of debt, with four clubs having borrowings over £100 million, including Brighton £148 million, Cardiff City £116 million and Blackburn Rovers £104 million. Bolton Wanderers have not yet published their 2015 accounts, given their much-publicised problems, but their debt was a horrific £195 million in 2014.

That said, the vast majority of this debt is provided by owners and is interest-free, so the amounts paid out by Championship clubs in interest is a lot less than you might imagine.

The decrease in the cash balance is concerning, with Purewal sounding a note of caution: “Cash flow is difficult in this business, but we do have some in hand. We’re not overdrawn. Going forward, depending how the team does that is, potentially, another story, with the parachute payments stopping.”

Unfortunately the club accounts do not include a cash flow statement for 2007/08 (Steve Morgan’s first season), but in the seven years since we can see how the club has used his £30 million capital injection, though this was also boosted by £30 million generated from operating activities and £2 million of interest received.

Around £16 million has gone on net player registrations (£66 million of purchases less £50 million of sales), but the vast majority £35 million has gone on capital expenditure, largely the stadium redevelopment and the Compton Park Academy (which cost around £10 million including land acquisition).

Arguably, the real cost of this investment has been Wolves’ place in the Premier League, especially as £14 million of this infrastructure investment took place after relegation, which has hamstrung any attempt to return to the top table.

Although grateful for Morgan’s £30 million funding, many supporters believe that his lack of investment since then has hurt the club’s prospects. They would look enviously on the money provided by other owners in the Championship, e.g. Tony Bloom has put in over £200 million at Brighton, Steve Gibson at least £130 million at Middlesbrough and Matthew Benham £76 million at Brentford.

In any case, Morgan put the club up for sale last October, also stepping down as chairman. There has been much speculation for his reason for doing so. It might be as simple as re-assessing his commitment, especially after a divorce and meeting a new partner, though others believe that he might be unwilling to put enough money in to fund a genuine promotion campaign, especially now that the parachute payments have run out.

"I could be happy"

Whatever his reason, finding a new owner can be a lengthy process, as Moxey explained: “Despite what many people think there are not many people around with tens of millions that want to buy a football club. So many clubs are up for sale. So few get sold. They require constant funding to keep them afloat.”

He added, “We don't just want to sell to anybody. Many of our older fans remember when this club nearly went out of business. We don't want a return to those days.”

In the meantime, Wolves are gambling on youth, underpinned by its Category 1 Academy accreditation status. In fact, Wolves are one of only 23 clubs in the entire country to hold such a licence.

"Coady Island"

The danger, of course, is that the club will have to sell some of their acclaimed young players to help balance the books. It’s also asking a lot of these youngsters to achieve the club’s stated objective of gaining promotion back to the Premier League as soon as possible.

It does look as if a change in ownership might be the best thing for Wolves. Moxey hinted at this: “We would like new investment if we can get it. A new owner potentially comes with new investment policies.”

Either way, few fans would disagree with the chief executive’s assertion that, “Ideally, we want to be challenging for promotion regardless of ownership. I think being in the top six, if at all possible, is a minimum requirement.”

Either way, few fans would disagree with the chief executive’s assertion that, “Ideally, we want to be challenging for promotion regardless of ownership. I think being in the top six, if at all possible, is a minimum requirement.”

0 comments:

Post a Comment