After a disappointing 2014/15 season, when they flirted with the relegation zone before recovering to finish seventh, Borussia Dortmund came back with a bang in 2015/16. Under new coach Thomas Tuchel, the Schwarzgelben once again emerged as Bayern Munich’s main challengers, finishing second in the Bundesliga, losing in the German Cup final and reaching the Europa League quarter-finals where they lost to Liverpool.

This was a mightily impressive first season for Tuchel, whose team played an exciting, attractive brand of football, culminating in them being the highest scorers in the German top tier.

The former Mainz coach had an incredibly tough act to follow, as his predecessor, the charismatic Jürgen Klopp, was the most successful coach in Dortmund’s history. With him at the helm, the club won the league and cup double in 2012, the Bundesliga the previous year and reached the Champions League final in 2013, where they were defeated by (guess who) Bayern.

"Warrior of the Wasteland"

Tuchel comfortably embraced the challenge, though Dortmund are no strangers to bouncing back. Perhaps their most remarkable recovery is from the serious financial problems of a decade ago. They splashed out on expensive signings and high wages, effectively gambling on regular qualification for the Champions League to fund this massive spending.

When this was not achieved, they only succeeded in building up nearly €200 million of debts, leaving the club in a “life-threatening situation”. As chief executive Hans-Joachim Watzke admitted, the club was “a millimetre away from going bust.”

That was then, this is now, as evidenced by the latest 2015/16 financial results, which management described as “a successful year in which the club laid the foundations for competing in the coming 2016/17 UEFA Champions league season.”

Revenue grew by 36% to a record €376 million (€285 million excluding player sales), which Watzke described as “a clear sign of BVB’s earnings power”, while pre-tax profits surged €28 million to a hefty €34 million (€29 million after tax).

The main reason for the improvement was profit on player sales which shot up €61 million from just €2 million to €63 million, comprising transfer income €95 million less transfer expenses €32 million. This was largely due to the sales of Mats Hummels to Bayern Munich, Ilkay Gündogan to Manchester City, Kevin Kampl to Bayer Leverkusen, Ciro Immobile to Sevilla, Jonas Hofmann to Borussia Mönchengladbach and Kevin Grosskreutz to Galatasaray.

Excluding transfer fees, revenue rose €4 million (1.5%) from €281 million to €285 million. Match day was €7 million (17%) higher, mainly due to hosting four more European games than the previous season plus “moderate” price increases, while the other big riser was advertising, up €9 million (12%) to €85 million. Broadcasting was flat at €83 million with the income lost from not competing in the Champions League being effectively offset by an increase in Bundesliga TV money.

Other operating income fell €13.5 million from €17 million to €3.5 million, as there was no repeat of the previous season’s insurance payment from the policy taken out against the risk of not qualifying for the group stage of the Champions League. This is an interesting approach, given that such arrangements are banned in English football as a protection against match-fixing.

"This Charming Ousmane"

Following investment in the squad, the wage bill increased by €22 million (19%) from €118 million to €140 million, while player amortisation (including impairment) rose €6 million from €33 million to €39 million. Other expenses were up €12 million (11%) to €121 million, mainly from additional match day (catering) costs and higher performance-related advertising agency commissions.

On the other hand, net finance costs on loans fell sharply by €5 million (71%) from €7 million to €2 million, reflecting the debt reduction and lower interest rates.

As a technical aside, I am using the Deloitte definition of revenue here in order to facilitate comparisons with other European clubs, so have excluded €95 million of transfer income, but included €4 million of other operating income. Adding these adjustments to my revenue of €285 million gives the €376 million announced by Dortmund.

It is clear that “Borussia has developed itself economically and on a sporting level continuously over the last few years”, as Watzke put it. So much so, that they have now reported profits for six consecutive seasons, which the club said, “again demonstrated its economic stability.”

In fact, they have accumulated €161 million of pre-tax profits in this period, which represents a spectacular turnaround, as the club had reported losses in five of the previous six years, including €55 million in the annus horribilis of 2004/05 and €23 million the year after.

Indeed, Dortmund expect to post another profit (“net income”) for the 2016/17 season. In fairness, the Bundesliga is generally a profitable environment, with 11 of its 18 clubs making money in the 2014/15 season.

However, Dortmund would have made a €29 million loss without significant player sales in 2015/16. As the club put it, “Transfer deals at the end of the financial year more than offset the income lost from not competing in the Champions League.” The sales of Gündogan and Hummels might not have been popular, but they did help to balance the books.

Dortmund further explained, “A player might be sold based on financial considerations in cases where this would not have happened had the decision been made purely on the basis of sporting criteria.”

The increasing importance of player sales to Dortmund’s business model is evident: in the last four seasons transfer income averaged €41 million a season (profit €25 million), compared to only €14 million in the preceding four seasons (profit €8 million). The 2012/13 season was boosted by the sale of Mario Götze to Bayern Munich, while the comparison would have been even starker without the free transfer of Robert Lewandowski to Bayern in 2014 after the prolific striker ran his contract down.

Indeed, the 2015/16 season was the first time that transfer income (€95 million) represented the revenue item (in Dortmund’s terms) with the largest share (25%) of total revenue.

The high impact of player sales on Dortmund’s bottom line is set to continue, as the €42 million sale of Henrikh Mkhitaryan to Manchester United will be included in the 2016/17 accounts. Dortmund also retain many valuable “assets”, such as speedy forward Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang. In his case, Watzke said that the club would only discuss massive offers of €120 million, noting that “it was no coincidence that we renewed his contract until 2020.”

Dortmund have added EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxation, Depreciation and Amortisation) to their list of key performance indicators “in light of the rise in investment activities and the associated increase in depreciation, amortisation and write-downs.”

On this basis, Watzke said, “the club’s performance is more than comfortable”, as EBITDA shot up from €56 million to €87 million in 2015/16, though it should be noted that Dortmund’s definition includes net transfer income.

Using the more generally accepted definition of recurring income, i.e. excluding lumpy profits from player sales, the story is not quite so impressive. After many years of steadily rising EBITDA, this fell from €54 million to €24 million last season. That’s still not too shabby, but to place it into perspective, Manchester United have just announced EBITDA of €230 million, i.e. nearly ten times as much, so it’s not surprising that they could throw so much money at Mkhitaryan.

Even so, Dortmund’s revenue growth has been hugely impressive, rising by €177 million (165%) from €107 million six years ago, though it has slowed down a little since 2013 with the increase being only €29 million in the last three years.

Since 2010 the main driver of revenue growth has been commercial income, which has increased by €91 million (150%), but the two other principal revenue streams have also shot up: broadcasting by €61 million (291%) and match operations by €23 million (100%).

Dortmund “expect to generate” €340 million in 2016/17, though this includes transfer income, mainly from the Mkhitaryan sale. That said, “Other revenue items are expected to increase in the coming financial year.”

Indeed, excluding transfer income, investment analysts Edison forecast a €26 million increase to €311 million in 2016/17, thanks to the return to the Champions League, and a further €33 million increase to €344 million in 2017/18, due to the new BundesligaTV deal.

Dortmund’s main challenge, of course, is to compete with the titan that is Bayern Munich. The Bavarians’ 2014/15 revenue of €474 million is by far the highest in Germany, some €189 million more than Dortmund’s 2015/16 revenue of €285 million. The gap to their other domestic rivals is even higher: Schalke €254 million, Hamburg €355 million and Stuttgart €366 million.

Moreover, only Dortmund have kept pace with Bayern’s insatiable revenue growth. Since 2009, they have both increased revenue by around €180 million, while Schalke’s growth was around half of that at €95 million. Stuttgart were essentially flat and Hamburg’s revenue has actually declined.

As Dortmund said in their annual report, “revenue alone is not sufficiently meaningful, nevertheless it provides a clear indicator of the company’s economic strength, especially when compared against that of competitors.”

Watzke neatly summarised Dortmund’s position, “In the Bundesliga the challenge is to leave the clubs in third and below even further behind. We’ll never overtake Bayern Munich, but if we have a good year, we do have the opportunity to catch them in a sporting sense. But that would need Bayern to wobble. The problem is, that hasn’t happened for several years. Should they do so, then BVB wants to be in position.”

For the last four seasons Dortmund have been in 11th position in the Deloitte Money League, which is more than respectable. Watzke went one step further: “Dortmund is among the top ten clubs in Europe: we are a first-class address.”

The problem is that Dortmund’s €281 million was far below the leading clubs, such as Real Madrid €577 million, Barcelona €561 million, Manchester United €520 million, Paris Saint-Germain €481 million and (crucially) Bayern Munich €474 million. Not only that, but the gap is widening with the big three all announcing solid growth last season: Manchester United €690 million (at the average Euro rate of 1.34 for 2015/16), Real Madrid €620 million and Barcelona €612 million.

Watzke is acutely aware of this challenge: “We can't win the race against them. We could never compete with Real Madrid, Barcelona or Chelsea over a period of ten years. But this is not the target. As long as we try our best and battle, it's fine.”

If we compare Dortmund’s revenue with clubs in the 2014/15 Money League top ten, we can see that they face challenges across the board, as they are almost universally lower in each of the three main revenue streams, though they have done better commercially than Juventus, Liverpool, Chelsea and Arsenal.

On the other hand, this analysis highlights the scope for improvement in broadcasting income, which will be partially addressed by the new Bundesliga TV deal starting in 2017/18.

This is much needed, as the gap between Dortmund and the 10th placed club in the Money League widened in 2014/15 to €43 million, after being as low as €7 million in 2012/13. It is likely that this gap will further widen in 2015/16, as Juventus, the current 10th placed club, has announced 2015/16 revenue of €341 million, i.e. €56 million more than Dortmund.

From a domestic perspective, Dortmund’s revenue shortfall against the top club (Bayern Munich) was €193 million in 2014/15, which is only surpassed in France, where PSG are €371 million ahead of Marseille. However, the gap is much smaller in Italy, England and Spain.

Watzke does not seem too disheartened: “If you're a David, you feel and behave differently to when you're a Goliath. We do not complain that we are number two in Germany. If you're the challenger, you can act differently to the king. So for Bayern, it's an obligation to win; for us, it's an opportunity.”

Moreover, Dortmund benefit from a fairly large gap to the 3rd placed club in Germany, with their revenue being €61 million higher than Schalke. This is much more than the gaps in England, Italy and France, so Dortmund cannot complain too much. If Bayern should more often than not win the gold medal, Dortmund should similarly grab the silver.

As we have seen, the largest revenue category at Dortmund is commercial income, which accounts for more than broadcasting and match day combined. That said, the fastest growing revenue stream is broadcasting, up from 20% in 2010 to 29% in 2016. As a consequence, match day has diminished in importance from 22% to 16% over the same period.

Dortmund’s commercial revenue grew £10 million (7%) from €142 million to €152 million in 2015/16, mainly due to advertising, up €9 million (12%) from €76 million to €85 million, while merchandising and conference, catering and miscellaneous were relatively flat at €40 million and €27 million respectively.

Dortmund’s commercial revenue was the ninth highest in the 2014/15 Money League. Over the past few years, they have fallen down this league table, though this is partly due to a combination of “friendly” deals at PSG and Manchester City plus the favourable exchange rate for English clubs (which has now very much changed).

Nevertheless, the relative importance of commercial income to Dortmund remains clear, as is the case with other German clubs. They had the third highest percentage of their total revenue from commercial of any Money League club. This was only behind PSG, thanks to their deal with the Qatar Tourist Authority (worth a reported €200 million), and the commercial behemoth that is Bayern.

Despite their growth, Dortmund’s commercial income is still only around half of Bayern’s, partly due to the €38 million revenue the Bavarians earn from the Allianz Arena, though their sponsorship and merchandising are also much higher.

Bayern’s former president Uli Hoeness said that Dortmund would need to have a more consistent track record of winning trophies if they hoped to match Bayern’s global appeal, but in truth they’re doing very well compared to almost every other club on the planet.

The club’s commercial strategy is similar to Bayern’s, namely to establish strategic partnerships with long-standing partners. All three main sponsorship deals are long-term in nature: stadium naming rights partner Signal Iduna to 2026; shirt sponsor Evonik to 2025; and kit supplier Puma to 2020. Not only that, but each of these companies have acquired equity interests in the club: Evonik 14.78%, Signal Iduna 5.43% and Puma 5%.

On top of that, Dortmund have a 12-year agreement with marketing partner Lagardère (formerly Sportfive) until 2020.

"Close, but no cigar"

Another objective is to sign up many secondary sponsors, known as “champion partners”, and a lengthy list now includes the likes of Eurowings Aviation, Opel, Hankook Reifen, HUAWEI Technologies, Radeberger, Sparda Bank, Sprehe, Unitymedia and Wilo.

Internationalisation is a key element of Dortmund’s plans, as Watzke confirmed: “We are going to continue with our strategy and have identified two key markets. The main one at the moment is south-east Asia, but the US market is interesting as well.”

Dortmund gained additional sponsors as a result of the marketing activities in connection with the club’s Asia tour in July 2015. In light of the club’s “rapidly growing appeal” in the Region, they have opened their first representative office outside Germany in Singapore.

However, although the club has “huge commercial potential”, Watzke cautioned, “We shouldn’t kid ourselves. You can only become a big international brand by playing in the Champions League.”

According to some German press reports, Evonik, a chemical company, has increased its shirt sponsorship to €20 million a season, though this is still lower than the deals struck by Bayern (Deutsche Telekom) and Wolfsburg (Volkswagen), who both receive €30 million a season. The Evonik chairman has said that he is very pleased with Dortmund as a partner, due to their large crowds and sporting success (“in a very exciting way”).

Signal Iduna, the naming rights partner, has also increased its annual payment from €4 million to €5-6 million after the deal extension.

The payment from Dortmund’s kit supplier, Puma, has been reportedly increased after their capital injection, rising from €6-7 million a season to €15 million. Rather wonderfully, the shirt has the inscription “Echte Liebe” (true love) on the inside of the collar. That’s good news, but it is still far below Bayern’s new €60 million deal with Adidas (and, for that matter, the new kit deals at Real Madrid and Barcelona, which are worth €120-150 million according to press reports).

Dortmund’s broadcasting income was basically flat in 2015/16 at €83 million with the increase in BundesligaTV money, up €17 million to €61 million, offsetting the €15 million reduction in UEFA competitions to €17 million, due to playing in the Europa League compared to the Champions League the previous season, and the €2 million decrease in the German Cup to €4 million.

The increase in Bundesliga distribution was largely due to Dortmund’ successful performances in international club competitions over the previous five seasons and the resulting improvement in their UEFA coefficient ranking, as well as the increase in income from international TV rights.

TV revenue in Germany is divided among clubs via a points system, which ranks clubs proportionate to their league positions over the past five seasons. Performance is weighted in favour of the more recent years, so last season a factor of 5 was applied to 2014/15, 4 to 2013/14, 3 to 2012/13, 2 to 2011/12 and 1 to 2010/11.

However, a form of equality is then applied, as the club with most points from this algorithm only receives twice as much money as the club that has the lowest number of points. In this way, top club Bayern Munich received €40 million in 2015/16, while bottom club Darmstadt received €20 million.

Television income is not very high in Germany, as can be seen from the 2014/15 Money League, where Dortmund sat in 18th position. Their total broadcasting revenue of €82 million was only around 40% of the €200 million earned by Barcelona and Real Madrid, who benefited greatly from their individual domestic deals.

It is therefore good news that the Bundesliga recently announced a new domestic TV rights deal with Sky and Eurosport for the four years from 2017/18 to 2020/21, which will significantly increase the money by 85% from €2.5 billion to €4.6 billion, working out to €1.160 billion a season. As the league advised that total rights would be worth €1.4 billion, that means that the international rights will also rise to €240 million a season.

According to broker research, Dortmund’s share of the TV revenue should rise to around €90 million a season, but this is still a lot less than the money earned in England. The new Premier League deal is likely to deliver €150-200 million to the top four English clubs, depending on the Euro exchange rate. Watzke, for one, is unmoved: “I have no fear of the English, we must make sure our qualities are in the foreground.”

The new Bundesligatotal of €1.4 billion will take it ahead of Serie A (€1.2 billion) and Ligue 1(€0.8 billion), but they will still lag behind La Liga (€1.5 billion) and obviously be miles below the Premier League (€3.4 billion).

However, the Bundesliga’s chief executive, Christian Seifert, noted, “We are now number two behind the Premier League (in terms of domestic rights).” Although he described the TV market as challenging, Seifert did emphasise the growth prospects: “Germany is the biggest single market in Europe, but pay-TV still does not have the market position of other countries. There is a lot of potential though.”

Some believe that the relatively low amount paid for international rights can be ascribed to Bayern’s dominance, which has made the league boring, but Seifert argued that overseas interest was not purely in the title winners: “Last year we saw very competitive games to decide who will play in the Champions League, who will play in the Europa League or relegation.”

The other main element of broadcasting revenue is European competition, though Dortmund’s receipts have plummeted since 2012/13, when they earned €54 million for reaching the Champions League final. In comparison, in 2014/15 they received €33 million after being eliminated at the quarter-final stage by Juventus.

UEFA have not yet published the revenue distribution details for 2015/16, but the club stated that they received €14 million for battling through eight rounds of the Europa League (the other €3 million from UEFA competitions was a surplus payment from the previous season).

It is therefore very positive that Dortmund have returned to “the world’s premier club football competition” in 2016/17, especially as the Champions League prize money has increased in the latest TV three-year cycle.

Dortmund’s payment will be influenced by the amount they receive from the TV (market) pool. Half depends on the progress in the current season’s Champions League, while half depends on the position that the club finished in the previous season’s domestic league (1st place 40%, 2nd place 30%, 3rd place 20% and 4th place 10%).

Although Watzke has claimed that Dortmund is no longer economically dependent on Champions League money, thanks to their long-term sponsorship contracts, it is clearly a major differentiator with other German clubs.

In the five years up to 2014/15, Dortmund received €152 million TV money, which was only exceeded by Bayern’s €224 million. However, they greatly benefited compared to others with only Schalke €21 million and Bayer Leverkusen €57 million being anywhere near them.

Dortmund’s match day revenue rose €7 million (17%) to €47 million in 2015/16, largely due to the Europa League, where the eight home matches (including two qualifying rounds) contributed to €13.4 million from UEFA competitions. In addition, there was €27 million from the Bundesliga, €3.7 million from the German cups and €2.3 million from friendlies.

Their incredible average attendance of 81,178 was the highest in Europe, ahead of Barcelona 78,250, Manchester United 75,300 and Real Madrid 67,700. Not only is Dortmund’s attendance easily the highest in Germany with the next teams being Bayern 75,000 and Schalke 61,386, but it has also been the highest for the past 18 seasons.

The Dortmund fans’ interest shows no sign of slowing down, as they have established a new Bundesliga record for season tickets at a mighty 55,000 – and that is capped to ensure an adequate supply of tickets on the day of the match.

It therefore might be a little perplexing to see that Dortmund are nowhere near the highest match day revenues in the Money League with only €54 million in 2014/15 (Deloitte definition), while the likes of Arsenal, Real Madrid, Barcelona and Manchester United all generate €115-130 million. There are two obvious reasons for this huge discrepancy: fewer matches and low ticket prices.

There are two fewer home games every season in the Bundesliga, while last season Dortmund only played four Champions League home games and one in the DFB Cup. This resulted in a total of 22 home games compared to 26-29 for the leading clubs in other major leagues.

That said, Dortmund’s average revenue per match of €2.5 million is still only around a half of the money earned by Manchester United (€5.4 million) and Arsenal (€4.9 million). It is also much lower than the amount pocketed by Bayern (€3.6 million).

Dortmund’s high attendances (and small match day revenue) can be partially attributed to the large number of standing places, including the famous Südtribüne terrace, known as the “Yellow Wall”, which is the largest standing area in European football and provides each home game with an intense, passionate atmosphere.

Watzke explained the thinking: “Terrace culture is extremely important for football. We’re demonstrating that football has to remain affordable – as opposed to, say, England. A club can show that by offering standing tickets that cost between 11 and 14 Euros. I’m not sure how many clubs in Europe offer 28,000 standing tickets, but I’d presume we are the only one. That way we can sharpen our club’s social profile. Of course BVB wants to earn money, but it’s vital that football remains a mass phenomenon.”

This was endorsed by marketing director Carsten Cramer, “We will never increase our match day revenue, because we are really concerned about (preserving) low-level pricing – that people of all social classes are able to come to the matches.”

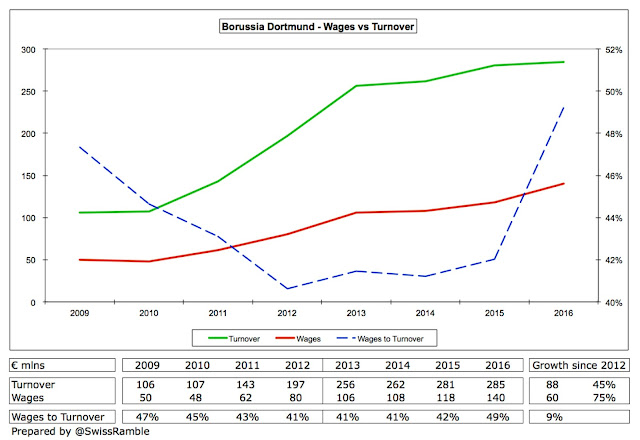

The wage bill rose by €22 million (19%) from €118 million to €140 million in 2015/16, which means that wages have increased by 75% in just four years, comfortably outpacing revenue growth of 45% in the same period.

This means that the important wages to turnover ratio has risen to 49% (excluding transfer fees), significantly higher than the 41-42% range achieved between 2012 and 2015, but just below the 50% targeted by the Bundesliga.

Moreover, the club “expects personnel expenses to increase in the coming financial year due to the strengthening of the squad with quality players.” On the face of it, this might be concerning (at least from a financial perspective), but the club clearly links wages to revenue: “Personnel expenses are largely dependent upon the club’s sporting success, because the professional squad is compensated on the basis if its performance, meaning that only those expenditures commensurate with the club’s success are expected.”

Even after this growth, Dortmund’s wage bill is still around €100 million lower than Bayern (€227 million in 2014/15). In fairness to the Bavarians, their revenue is also substantially higher, but that does not make it any easier for Dortmund to compete.

This point is even more relevant on the European stage, where some of the leading clubs can boast wage bills far higher than any in Germany, e.g. Barcelona, Real Madrid, Chelsea, Manchester United, PSG, Manchester City and Arsenal are all above €250 million (though the Spanish figures are inflated by other sports).

In 2014/15 Dortmund’s wages were 13th highest of the top 15 clubs in the Money League, while their wages to turnover ratio was easily the lowest. Even after the 2015/16 rise to 49%, it would still be below all the others with the exception of Bayern. As Watzke observed, “We’ll always need creativity to close the gap to clubs like Paris Saint-Germain, Manchester City and Manchester United.”

The other staff cost, player amortisation, rose to €39million, though this included an unexplained €7 million write-down in player values (impairment), so the pure amortisation was only €32 million. This has sharply risen from €8 million in 2012, reflecting Dortmund’s increasing activity in the transfer market.

However, this is still not very high for a leading club, as Dortmund have a long way to go before being described as big spenders. As a comparison, player amortisation at big spending Manchester United and Real Madrid is over €100 million, while Bayern booked €61 million.

To explain this concept, transfer fees are not fully expensed in the year a player is purchased, but the cost is written-off evenly over the length of the player’s contract. As an example, André Schürrle was reportedly bought from Wolfsburg for €30 million on a five-year deal, so the annual amortisation in the accounts for him will be £6 million.

In contrast, other expenses of €121million seem fairly high, though this does include €41 million for match operations, €26 million materials, €24 million advertising, €17 million administration and €8 million retail. Note: I have excluded transfer expenses from my definition.

After their previous extravagant approach, Dortmund followed a thrifty strategy in the transfer market, balancing the books between 2005 and 2013 with a zero net spend, including average annual gross spend of just €12 million. However, in the last four years there has been a clear shift in policy. Although the net spend still averages only €10 million, the gross spend has dramatically increased to €62 million.

As Dortmund put it, “In order to successfully compete on the international stage and in the Champions League, we rebuilt our squad this year. The club invested nearly €100 million to sign a mix of experienced, top quality players and young talent.”

"Schürrle as I am"

This summer they signed German internationals Mario Götze, returning after three years with Bayern, and André Schürrle, plus two players who shone at the Euros, Raphael Guerreiro (Portugal) and Emre Mor (Turkey).

They have also maintained their focus on “value development”, such that “transfers should create substantial earnings potential”, as well as “sustainable sporting competitiveness”, by signing Marc Bartra from Barcelona, Sebastian Rode from Bayern and the exciting Ousmane Dembélé from Rennes.

That said, Dortmund are still something of a selling club, as CFO Thomas Treß admitted, “We are not able to compete in the European soccer market with British or Spanish clubs in respect of transfer pricing.”

In addition, the lure of Bayern has proved too strong for three of Dortmund’s stars in the last four years: Götze, Robert Lewandowski and key defender Mats Hummels. As you might imagine, Watzke takes a dim view of this: “Bayern Munich want to destroy us. They have helped themselves to our players, so we wouldn’t be a danger.”

Even though Dortmund have started to spend reasonable sums in the last four years, totaling €42 million net, Bayern have still spent more than twice as much with €95 million. That is to be expected, but of more concern is the fact that new boys RB Leipzig have actually spent most in the Bundesliga with a cool €100 million.

There is further strong evidence of Dortmund’s financial recovery with the elimination of debt in the last two years (excluding finance leases). In 2006 gross debt was as high as €191 million, but Dortmund now have net funds of €52 million.

Watzke was rightly proud of this achievement, “We don’t have to pay any more interest, no more repayments. That will mean that we can increase the budget.” In fact, the club can reduce its payments on interest and principal by €5-6 million a year.

Dortmund had to commit 9.1% of its revenue to interest payable in 2008, but this has been slashed to just 0.7% in 2016, mainly for expenses from finance leases.

Dortmund have generated positive net cash flow for five of the last six years, though 2015 was only achieved due to the club raising €141 million of new share capital. Moreover, there was a small negative cash outflow of €2 million in 2016, even though player registrations and loan/interest repayments were reduced.

In the last eleven years Dortmund have had €491 million of available cash: €306 million from operating activities plus €185 million from share issues. Over half of this has been spent on financing: €170 million of debt repayments, €61 million on interest payments and €23 million on dividends (paid since 2013).

Just €107 million (22%) has been spent on player purchases with €59 million (12%) on capital expenditure, while €23 million (5%) has gone to the tax man. The other notable “use” of cash over that period has been to increase the cash balance, which has risen by €48 million.

Perhaps the biggest threat to Dortmund’s position in Germany is the way clubs have started to get round the “50+1” rule, which dictates that members must own a minimum of 50% of the shares plus a deciding vote, theoretically preventing a club from being subject to the whims of an individual owner and taking on excessive debt.

However, RB Leipzig, owned by Austrian energy drink manufacturer Red Bull, have implemented a scheme whereby a member must pay €800 a year (compared to Bayern’s €60) and they reserve the right to reject any application without justification. This may not break the letter of the rule, but it is clearly against the spirit.

"Greece is the word"

Watzke’s views on the nouveaux riches are pretty strong: “It is a scandal that a pure marketing branch office of an Austrian beverage producer can compete in the highest division in Germany.”

In addition, there are other “company clubs” such as Leverkusen (Bayer), Wolfsburg (Volkswagen), though they were set up many years ago by the workers at both plants. Then there’s Hoffenheim, whose rise through the leagues was bankrolled by the software billionaire Dietmar Hopp.

For the time being, we should simply enjoy the fabulous spectacle at Dortmund, where they have proved that a football club can succeed without just throwing money at the problem. First-class management, astute scouting and a belief in youth development have delivered trophies to some of the best fans around, while the team’s dazzling displays have gained admirers throughout Europe.

"Return of the Marco"

Nevertheless, Dortmund are not immune to today’s financial pressures, so even they have started to spend more to remain competitive, with both their transfer spend and wage bill rising – though still nowhere near the levels of Europe’s elite.

Let’s leave the last word to Watzke: “We need to be the second major force in German football in the long-term. We’ve come a long way to achieving that and we want to be among the top clubs in Europe as well. That’s not unrealistic, even though it is an ambitious target for a club from a town of only 600,000 people up against teams from the biggest cities in Europe. But we are ambitious!”

Let’s leave the last word to Watzke: “We need to be the second major force in German football in the long-term. We’ve come a long way to achieving that and we want to be among the top clubs in Europe as well. That’s not unrealistic, even though it is an ambitious target for a club from a town of only 600,000 people up against teams from the biggest cities in Europe. But we are ambitious!”

0 comments:

Post a Comment