This has been a challenging season for Ipswich Town, as they have been poor in the league and recently suffered a humiliating, televised defeat in the FA Cup against non-league Lincoln City. Manager Mick McCarthy appears to retain the support of the board for the time being, but he has clearly lost many of the fans.

This feels a little harsh on the experienced Yorkshire man, who has arguably enabled Ipswich to punch above their weight during his tenure. When he replaced Paul Jewell in November 2012, Ipswich were bottom of the Championship, but McCarthy successfully guided the club out of the relegation zone to finish in a comfortable 14th place.

Since then he has registered three successive top ten finishes. His first full season in 2013/14 ended in a respectable ninth place, before he led them to the play-offs in 2014/15. Last season Ipswich came a somewhat disappointing seventh, but this was still ahead of many wealthier clubs.

As McCarthy pointed out, “This is the first year that it’s been a struggle.” To an extent, he has been a victim of his own success, as he reached the play-offs on a shoestring budget, getting the most out of a fairly average squad.

"Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence"

This reinforced the cautious approach of Marcus Evans, who has frequently spoken of his determination to take Ipswich to the Premier League since he bought 87.5% of the club in December 2007, but has equally often been accused of lacking the ambition to do so.

Evans summarised his philosophy last month: “My view, based on the finances available to us compared to those with parachute budgets and the small group with, often short term, huge owner investment, is for the club to maintain a sustainable and consistent strategy, which I firmly believe provides a foundation each season for a promotion challenge.”

He then outlined the key elements of his strategy, “In summary, a focus on the Academy; a competitive wage structure; careful use of our transfer budget on developing players and a stable management team are factors which I believe provide us with the best chance of promotion out of the Championship, which is one of the toughest - and getting even tougher - leagues in the world.”

Managing director Ian Milne was singing from the same song sheet: “Marcus has gone for sustainability and Mick understands that. You can achieve good things through getting the right people in your club and working as a team from top to bottom.”

"A Grant don't come for free"

While all this is undoubtedly true, the concern is that this conservative stance will mean a continuation of the 15-year groundhog day existence that Ipswich have held in the Championship (or equivalent) since relegation from the top flight in 2002. To paraphrase U2, it feels like Ipswich are “stuck in a moment – and they can’t get out of it.”

Initially, Evans provided his managers with enough funding to be competitive in the transfer market, but this did not achieve the desired objective, as first Roy Keane, then Jewell essentially wasted the owners’ cash with a series of poor choices. Not only did these expensive purchases not deliver on the pitch, but they ended up being offloaded for peanuts, leading to large financial losses arising from misplaced recruitment.

Having had his fingers burnt, Evans opted for a change in strategy: “I wanted to work with a manager who was going to try to and coach and make our players better, rather than give the manager the opportunity (to simply buy players).”

"Don't Luke back in anger"

The owner explained: “You would have hoped that money had resulted in better things, but look at Nottingham Forest – they lost £25 million last year and got nowhere. There are a lot of clubs out there that spent a lot more than Ipswich did and who ended up in exactly the same situation.”

The drive to more sensible cost management was also influenced by the introduction of the Financial Fair Play rules, which essentially aim to force clubs to live within their means.

As a result, in the past few years Ipswich have focused on free transfers, loans and swap deals, while trying to bring through young players from the Academy into the first team. As Milne explained, “We do have a very good scouting network and that enables us to get players at the minimum transfer fee.”

Consequently, Ipswich have averaged annual gross spend of only £0.5 million in the last four seasons (though the January 2017 transfer window has not yet closed), compared to £5.6 million a season in the first three years of the Evans era. In the same periods, average net spend of £4 million has flipped to average net sales of £4 million, an £8 million reduction.

Last summer’s spending was a good example of Ipswich’s policy: two promising young players were acquired in the shape of Grant Ward from Tottenham Hotspur and Adam Webster from Portsmouth at a combined cost of £1.4 million, while there were a couple of free transfers, including the veteran journeyman Leon Best from Rotherham United.

Evans argued that there was also money splashed out on loan fees and wages needed to tempt Premier League clubs to release players, including Welsh internationals Tom Lawrence (from Leicester City) and Jonny Williams (from Crystal Palace) and Conor Grant (from Everton), but Ipswich supporters would justifiably point out that the club failed to replace forward Daryl Murphy, who was sold to Newcastle United.

Ipswich’s parsimony can be seen by looking at the gross spend of Championship clubs this season, when only six clubs spent less than the Tractor Boys. These included two clubs with transfer embargoes (Blackburn Rovers and Nottingham Forest) plus a few “minnows”, i.e. Preston North End, Burton Albion, Rotherham United and Wigan Athletic.

The more meaningful comparison is with clubs seeking promotion, as Evans himself noted, “Newcastle and Norwich spent more than £100 million between them on transfer fees in the August window as they chase an immediate return to the Premier League.” Although this was actually factually incorrect, his point was still valid as Newcastle and Aston Villa have spent £55 million and £52 million respectively. Other big spenders include Fulham £22 million, Derby County £14 million, Wolverhampton Wanderers £11 million and Bristol City £11 million.

Many managers would use this low spending as an excuse for not meeting their objectives, but McCarthy is made of sterner stuff, saying that he won’t “stamp his feet” over the restricted transfer budget given to him by Evans. Instead, he sees it as his job to get more out of the players he’s got.

That said, he would like his achievements to be recognised: “I’ve done a bloody good job under the terms and conditions. I’ve sold Murphy, I’ve sold Mings, and others, and we’ve stayed competitive.”

Despite this prudent policy, Ipswich reported a £6.6 million loss in 2015/16, a £12.1 million deterioration from the previous year’s £5.5 million profit, though this was almost entirely due to a £11.5 million reduction in profits on player sales. These dropped from £12.2 million in 2014/15, due to the sales of Tyrone Mings to Bournemouth and Aaron Creswell to West Ham, to only £0.6 million.

The wage bill rose by £0.6 million (4%) from £16.0 million to £16.6 million as “further funds were invested in the squad to challenge for the play-off positions.” Other expenses also increased by £0.3 million (6%) to £5.4 million, but player amortisation dropped by £0.5 million (74%) to just £0.2 million.

Revenue slightly decreased by £0.1 million (1%), mainly due to a £0.4 million (9%) reduction in commercial income to £4.4 million, offset by broadcasting income rising by £0.3 million (6%) to £5.4 million. Gate receipts were unchanged at £6.5 million, as the club’s share of receipts from the League Cup tie against Manchester United at Old Trafford compensated for a fall in attendances and the money from the previous season’s play-off appearance.

Although a £7 million loss might not sound overly impressive, it has to be assessed in the context of England’s second tier, where the harsh reality is that most clubs are loss-making, largely as a result of their natural desire to reach the lucrative Premier League.

In this way, none of the Championship clubs that have so far published their 2015/16 accounts has been profitable with some reporting hefty losses: Brighton and Hove Albion £26 million, Hull City £21 million, Reading £15 million and Bristol City £15 million. As Evans lamented, “Wouldn’t it be nice… if you could turn a profit in the Championship, but I’m afraid that’s not the case.”

One way a football club can compensate for operating losses is via player sales, but Championship clubs have struggled to make big money sales with the highest amount reported so far last season being Hull City’s £13 million – and they had Premier League players to offload following relegation in 2015.

However, Ipswich’s profit on player sales of £0.6 million was one of the lowest in the division – in contrast to 2014/15 when their £12.1 million profit was only surpassed by Norwich City’s £14 million. Of course, next year’s accounts will be boosted by the £3 million sale of Daryl Murphy to Newcastle.

Ipswich have only reported a profit once in the Evans era, the £5 million in 2014/15, losing money in the other eight years. However, it is noticeable that the losses have been reducing, effectively capped at £7 million in the past three seasons.

As Milne explained, “In 2012 the annual losses peaked at £16 million and we started to go down a slightly different route.” That was actually the third worst loss in the Championship that year and served as a major wake-up call.

The reason for this large deficit were given by finance director Mark Andrews, “We brought in some experienced players in the 2011/12 season, Paul Jewell’s first season in charge, which kept the playing squad costs high.”

However, Ipswich’s best results in recent times have been boosted by large profits on player sales, as seen in 2014/15. Without the sales of Mings and Cresswell, the reported profit of £5.5 million would have been a loss of £6.7 million, i.e. in line with the £7 million losses in 2013/14 and 2015/16.

It was a similar story in 2011/12 when this activity contributed £10.8 million, largely due to the transfers of Connor Wickham to Sunderland for £8 million and Jon Walters to Stoke City for £2.75 million. Without these sales, Ipswich would have registered another big loss of £14 million.

The owner has said that his funding “would eventually be unsustainable without the benefits of transfer revenues from time to time to offset the club’s running costs.” Interestingly, the club has made more money from cheap, young players rather than experienced professionals. This was acknowledged by Evans: “We lost some good players in the past who were out of contract”, i.e. could leave for very little or even nothing.

To get an idea of underlying profitability and how much cash is generated, football clubs often look at EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Depreciation and Amortisation), as this metric strips out player trading and non-cash items. In Ipswich’s case this highlights the changed strategy after 2012, as EBITDA has improved from minus £9 million in 2012 to minus £6 million in 2016 (though this was a million worse than the previous year).

This might not sound overly impressive, as it is still negative, but it has to be put into the context of the Championship, where very few clubs manage to generate cash. Apart from Blackpool with their “unique” approach to running a football club, no Championship has reported EBITDA higher than £1.5 million in the last two seasons (in stark contrast to the Premier League where in the same period every club enjoyed positive EBITDA, except the basket case that is QPR).

Revenue has fallen by £1 million (6%) from the recent £17.2 million peak in 2011, which was boosted by reaching the Carling Cup the semi-final and a profitable FA Cup match at Chelsea.

All revenue streams have fallen since then, especially commercial income, which is 13% (£0.7 million) lower, though this is partly due to a decision to outsource catering (and thus only including net royalty payments in revenue). Gate receipts have rebounded, even though attendances have fallen, partly due to ticket price increases.

Following the slight reduction in 2015/16, Ipswich’s revenue of £16 million remains firmly in the bottom half of the Championship, a long way behind the top three clubs, who all earned more than £40 million. Of course, to a large extent, this only demonstrates the importance of parachute payments for those clubs relegated from the Premier League.

This is clearly a sore point for Evans, “The average parachute club starts with a £20 million per season head start over the rest of us.” He added, “The lack of parity in the game certainly makes it harder to compete. This season there were nine clubs benefiting from parachute payments and there will be something similar next year. That gives them a massive financial advantage.”

If these parachute payments were to be excluded, the gap would obviously reduce, but Ipswich’s £16 million would still be a fair way behind many other clubs, e.g. Brighton £25 million, Leeds United £24 million and Derby County £21 million. Given these stats, Ipswich’s performance in the last three seasons is worthy of some praise.

The mix of Ipswich’s revenue has changed over the years with broadcasting rising from 13% in 2009 to 33% in 2016 and commercial falling from 41% to 27%. However, match day remains the most important revenue stream at 40%, even though it has declined from 46%.

Unsurprisingly, this means that Ipswich are one of the Championship clubs most reliant on gate receipts. In percentage terms only four clubs had a higher dependency in 2014/15: Nottingham Forest, Charlton Athletic, Brighton and Millwall.

Gate receipts were flat at £6.5 million in 2015/16, even though average attendance fell by 644 (3%), as this was offset by one additional home cup game. Nevertheless, Ipswich’s match day revenue is the 9th highest in the Championship, though still around £3 million lower than Brighton £9.4 million and Leeds United £9.2 million.

Ipswich’s average attendance of 18,959 was actually the 8th best in last season’s Championship, but a fair way behind clubs like Derby County (29,663), Brighton (25,583) and Middlesbrough (24,627).

Ipswich’s attendances had been on a declining trend for a number of years, but the charge to the play-offs resulted in an upswing in 2014/15. However, they have started to fall again since then with a further slump this season to 16,789, which means that Ipswich have lost a third of their crowd since the recent 25,651 peak in 2004/05.

Evans is acutely aware of the reduction in spectators: “We can’t deny that attendances have been falling away somewhat this season – an indication of the disappointing results we have had this year.”

He said that the club was “looking at creative ways of getting supporters back to Portman Road.” These include low prices for youngsters (e.g. the season ticket for under-11s has been held at just £10 for nine successive years), interest-free direct debit monthly payment scheme and discounts with local businesses. If Ipswich are promoted to the Premier League, the season ticket will be upgraded at no extra price plus the holder will be given a free season ticket.

However, fundamentally Ipswich’s ticket prices are among the most expensive in the second tier. According to the BBC’s Price of Football survey, no other fans in the Championship pay more for the most expensive season ticket, while Town’s prices for the cheapest season ticket are only surpassed by three clubs (Brighton, Newcastle and Norwich City).

From 2003 to 2013 season ticket prices had remained frozen for seven out of the 11 years. However, prices have gone up every year since 2014/15, including a 1.5% increase for the 2017/18 season (in line with the retail price index).

Ipswich’s broadcasting revenue rose 6% (£0.3 million) to £5.4 million in 2015/16, which was attributed to an increase in the Football League basic distribution. In the Championship most clubs receive the same annual sum for TV, regardless of where they finish in the league, amounting to around £4 million of central distributions: £2.1 million from the Football League pool and a £2.3 million solidarity payment from the Premier League. There are also payments for each live TV game: £100,000 home; £10,000 away.

However, the clear importance of parachute payments is once again highlighted in this revenue stream, greatly influencing the top nine earners in 2014/15. Nevertheless, it should be noted that these payments are not necessarily a panacea, e.g. Middlesbrough secured promotion last season, even though their broadcasting income of £6 million was less than half the size of those clubs boosted by parachutes.

Looking at the television distributions in the top flight, the massive financial chasm between England’s top two leagues becomes evident with Premier League clubs receiving between £67 million and £101 million in 2015/16, compared to the £4 million in the Championship. In other words, it would take a Championship club more than 15 years to earn the same amount as the bottom placed club in the Premier League.

The size of the prize goes a long way towards explaining the loss-making behaviour of many Championship clubs. This is even more the case with the new TV deal that started in 2016/17, which will be worth an additional £35-60 million a year to each club depending on where they finish in the table.

Even if a club were to finish last in their first season in the top flight and go straight back down, their TV revenue would increase by an amazing £95 million. They would also receive a further £71 million in parachute payments, giving additional funds of around £166 million. If they survived another season, you could throw in another £120 million.

Of course, if they did go up, Ipswich would also have to spend more to strengthen their playing squad, but the net impact on the club’s finances would undoubtedly be positive, as evidenced by the improvement in the bottom line for those clubs promoted in the past few seasons.

As we have seen, parachute payments make a significant difference to a club’s revenue and therefore its spending power in the Championship. From this season, these will be even higher, though clubs will only receive parachute payments for three seasons after relegation. My estimate is £83 million, based on the percentages advised by the Premier League (year 1 – 55%, year 2 – 45% and year 3 – 20%), including around £40 million in the first year. However, if a club is relegated after only one season in the Premier League, it will only benefit from parachute payments for two years.

There are some arguments in favour of these payments, namely that it encourages clubs promoted to the Premier League to invest to compete, safe in the knowledge that if the worst happens and they do end up relegated at the end of the season, then there is a safety net. However, they do undoubtedly create a significant revenue disadvantage in the Championship for clubs like Ipswich, as Evans has often stated.

It is worth noting that if Ipswich were to be promoted, then they are contractually bound to make additional payments to players, coaches, staff, players’ former clubs, season ticket holders and certain convertible loan note holders. This is not quantified in the latest accounts, but was given as £8.2 million in 2013.

Commercial income fell by 4% (£0.4 million) to £4.4 million in 2015/16, though this is a little misleading, as the match day public catering operation was outsourced whereby the club now receives a royalty based on turnover.

Corporate sales and sponsorship were also slightly down on last year, however merchandise sales exceeded 2014/15, further building on the success of the change of kit supplier to Adidas in 2014 (a four-year deal). This was the first time Ipswich had worked with the German supplier since the glory days 35 years ago when they won the FA Cup and UEFA Cup under Bobby Robson.

The shirt sponsorship is with the Marcus Evans Group, who originally signed a five-year deal in 2008 worth a reported £4 million in total and have subsequently extended this each season.

There is clearly room for improvement in the commercial area, though to be fair only two Championship clubs (QPR and Leeds United) generate more than £10 million a season. This is basically down to results, as Evans admitted: “We work very hard maximising revenues for the club on a commercial basis, but ultimately our product is about what the team delivers on the pitch. And, like any business, if your product is of good quality, you’ll make more money and sell more of your product.”

Ipswich’s wage bill increased by 4% (£0.6 million) to £16.6 million, as full-time headcount was up from 142 to 149, leading to the wages to turnover ratio rising from 97% to 102%.

This was the second year in a row that wages have climbed, a necessary evil for Town, as explained by Ian Milne when commenting on the 2014/15 figures: “The wage bill has gone up this season quite appreciably. People say ‘where has the Tyrone Mings and Aaron Cresswell money gone?’ Well that’s where it is being ploughed into.”

Nevertheless, wages are still 8% below the £18.0 million peak in 2012, when the wages to turnover ratio was as high as 119%. Milne again: “We’re not paying under the market value, but the important thing is that we’re not paying over the market value either – which is something we have done in the past. Back in 2012 (when the club made a loss of £16m) we were paying some very high salaries.”

Clearly, the business model is still not ideal if revenue is not sufficient to cover the wage bill, let alone any other expenses, but almost every club in the Championship has a dreadful wages to turnover ratio with over half of them being more than 100%. In fact, Ipswich’s 102% looks positively reasonable compared to clubs like Brentford 178%, Nottingham Forest 170% and Blackburn Rovers 134%.

The £17 million wage bill was also firmly in the bottom half of the league, underlining the challenge in reaching the play-offs. In particular, it was significantly lower than the likes of Cardiff City, Fulham, Reading, Hull City, Blackburn Rovers and Nottingham Forest, whose wages were all above £30 million. This season it will be even worse with the arrival of big spending Newcastle United and Aston Villa in the Championship.

As Milne observed, “We certainly aren’t the highest spenders in terms of wages. We are paying more than we were, but I suspect it is still quite a bit less than some of the clubs that surround us.”

Of course, a high wage bill is no guarantee of success and it is also true that clubs have been promoted with a low wage bill, e.g. Burnley, but Ipswich’s relatively low wages certainly do not make it any easier.

Other expenses rose by £0.3 million (6%) to £5.4 million in 2015/16, largely as a result of a restatement of the Football League pension fund deficit (in accordance with Financial Reporting Standard FRS102) and general cost increases, but this was still on the low side, compared to clubs like Brighton £16.0 million, Fulham £13.4 million and Leeds United £12.6 million.

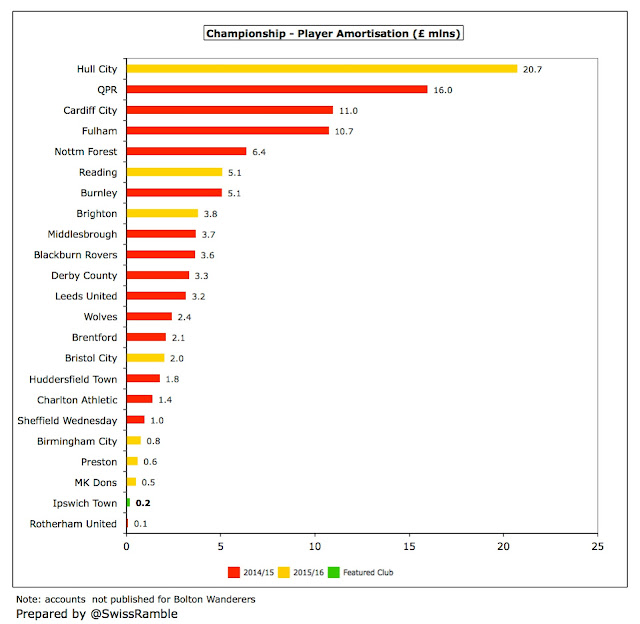

The recent lack of spending in the transfer market has been reflected in Ipswich’s profit and loss account via player amortisation, which has fallen from £5.1 million in 2009/10 to just £0.2 million in 2015/16.

In the same way, the lack of big money buys from other clubs has impacted the balance sheet with the value of player (intangible) assets decreasing from £6.4 million in 2010 to £0.3 million in 2016.

The accounting for player trading is fairly technical, but it is important to grasp how it works to really understand a football club’s accounts. The fundamental point is that when a club purchases a player the transfer fee is not fully expensed in the year of purchase, but the cost is written-off evenly over the length of the player’s contract, e.g. Grant Ward was bought from Tottenham for a reported £600,00 on a three-year deal, so the annual amortisation in the accounts for him is £200,000.

To place this into perspective, Ipswich’s player amortisation of £0.2 million is one of the lowest in the Championship, only ahead of Rotherham United. The highest player amortisation is obviously found at clubs recently relegated from the Premier League, namely Hull City £21 million, QPR £16 million, Cardiff City £11 million and Fulham £11 million.

Net debt fell by £0.7 million from £87.2 million to £86.5 million, as gross debt was reduced by £1.6 million from £88.2 million to £86.6 million, but cash also dropped by £0.9 million from £1.0 million to £0.1 million. Nevertheless, debt has shot up from the £36 million in 2008, which was largely taken on by Evans when he bought the club.

Almost all the debt is owed to various Marcus Evans’ companies, mainly through a mixture of loans and convertible loan notes. There are also £8 million of preference shares, which pay a fixed dividend of 7% per annum (provided there are profits available for distribution). To date, the club has accrued £4.8 million for these dividends. Against that, interest has not been charged on the Loan Notes 2026 from July 2014.

Of course, many clubs in the Championship have built up substantial debt, but Ipswich’s £87 million is only surpassed by five other clubs: QPR £194 million, Brighton £171 million, Cardiff City £116 million, Blackburn Rovers £104 million and Hull City £101 million.

The club has emphasised that it is not in debt to any financial institution, as explained by finance director Mark Andrews, “''Most Championship clubs are carrying debt but the majority of debt carried at Ipswich Town is not external, it is owed to the Marcus Evans Group.”

Milne added, “Marcus is very happy with the debt level – it’s all owed to him, none of it is owed to banks or anything like that. He, like a number of owners, doesn’t expect to get any of it back unless we get in the Premier League.”

This is indeed true, but there is still a degree of risk associated with such an arrangement, as the annual accounts noted: “the club remains dependent upon ongoing financial support from its principal shareholder.”

From a cash perspective Ipswich basically balance the books, but only because Evans increases his loan each year, as the cash flow from operating activities remains stubbornly negative. In the last decade Evans has provided £46.3 million via £32.8 million of loans and a £13.5 million increase in share capital. Financing has also come from £7.4 million of net player sales and a £1.5 million reduction in the cash balance.

However, the lack of investment over the last eight years is striking with just £0.2 million being spent on infrastructure improvements in the Evans era, i.e. virtually nothing on the stadium. Instead, almost all of the funding has been used to simply cover the club’s operating losses.

Former chief executive Simon Clegg explained Ipswich’s dependency on the owner a few years ago, “We only survive because Marcus Evans can afford to put in £4 million or £5 million of his own money every year to keep the club afloat”, while Evans repeated the mantra last December, “I am committing sums of £5 million and more per annum, at the start of each season towards the annual budget.”

That was certainly true in the past, but the cash flow statement shows that only around £400,000 of additional loans were received by the club in each of the last two seasons (net £250,000 after loan repayments), as the difference was largely compensated by player sales.

That may have changed this season, but Milne noted in a slightly worrying statement that, “You can’t keep expecting the owner to keep throwing money at things.”

Either way, Ipswich’s cash balance as at 30 June 2016 was down to just £91,000, one of the lowest in the Championship, though in fairness none of the clubs is sitting on a cash mountain.

One accusation against Evans’ ownership is that there has been a lack of transparency around the club’s affairs, epitomised by HMRC issuing a winding-up order in February 2016 for non-payment of tax, though this was subsequently dismissed – and described by Milne as “a storm in a tea cup”.

Yet the main charge is that the owner lacks ambition. The man himself has argued that this is not the case, effectively laying the blame at the feet of Lady Luck: “When I took over here I was hoping we would get to the Premier League in five years. I never had a firm expectation though. I realised that in football there are so many factors outside of your control.”

In fairness, Evans’ cautious approach has to be considered preferable to that applied by some owners (Bolton Wanderers, for example), especially for a club like Ipswich Town that experienced administration in the not too distant past.

"Hard to Berra"

In any case, he cannot simply buy success, as Ipswich need to comply with the Financial Fair Play (FFP) regulations. Evans had been a keen supporter of this initiative, “It is a key objective of the Board to reduce ongoing losses in order to meet the Football League’s FFP rules.”

However, he has become increasingly disillusioned, “FFP, which was brought in to level an increasingly uneven playing field hasn’t worked.” This is not just due to the advantage that parachute payments bring to clubs facing a cap on losses, but the application of the regulations.

Evans again, “At the moment it appears to be a total farce. However, let’s wait and see if the Football League does its job. I appreciate that legal wheels sometimes grind very slowly.”

Under the new rules, losses will be calculated over a rolling three-year period up to a maximum of £39 million, i.e. an annual average of £13 million, assuming that any losses in excess of £5 million are covered by owners injecting equity. A higher loss one year can be compensated in later years, e.g. via player sales, or might even become irrelevant (if the club is promoted).

"No Tears for Sears"

Basically, the allowable losses have increased, which is likely to encourage Ipswich’s rivals to spend even more, making the division even more competitive. For Ipswich to challenge, Evans would have to inject equity to maximise allowable losses.

It should be noted that FFP losses are not the same as the published accounts, as clubs are permitted to exclude some costs, such as depreciation, youth development, community schemes and any promotion-related bonuses.

These barriers help explain Ipswich’s focus on youth development, as explained by Evans: “I am 100% committed to the Academy and have recently invested over £1 million in new infrastructure and additional staffing. I believe our efforts of the last years are starting to pay off.”

Despite failing to secure the coveted Category One status, a number of talented players have emerged from the Academy over the last couple of years, e.g. Andre Dozzell, Teddy Bishop, Josh Emmanuel and Myles Kenlock. Furthermore, Town had three players in the England squad at last summer’s U17 European Championship.

"Teddy Picker"

Evans recently underlined his commitment, to Ipswich Town “I will continue to do everything I can to ensure that the success we want is just around the corner and that we are promoted.” However, he put his finger on the main issue in the very same statement, “There are those that feel my investment plan has no chance of success.”

This is a reference to the feeling that it is unlikely that a club like Ipswich could be promoted to the Premier League without the benefit of substantial investment, particularly in a world of ever more lucrative parachute payments to clubs relegated from the top flight.

It would indeed be a major surprise if Ipswich were to go up, especially given their current lowly position. Stranger things have happened, but not too often.

0 comments:

Post a Comment