-

This is default featured slide 1 title

Go to Blogger edit html and find these sentences.Now replace these sentences with your own descriptions.This theme is Bloggerized by Lasantha Bandara - Premiumbloggertemplates.com.

-

This is default featured slide 2 title

Go to Blogger edit html and find these sentences.Now replace these sentences with your own descriptions.This theme is Bloggerized by Lasantha Bandara - Premiumbloggertemplates.com.

-

This is default featured slide 3 title

Go to Blogger edit html and find these sentences.Now replace these sentences with your own descriptions.This theme is Bloggerized by Lasantha Bandara - Premiumbloggertemplates.com.

-

This is default featured slide 4 title

Go to Blogger edit html and find these sentences.Now replace these sentences with your own descriptions.This theme is Bloggerized by Lasantha Bandara - Premiumbloggertemplates.com.

-

This is default featured slide 5 title

Go to Blogger edit html and find these sentences.Now replace these sentences with your own descriptions.This theme is Bloggerized by Lasantha Bandara - Premiumbloggertemplates.com.

Monday, August 10, 2015

Juventus - From A Whisper To A Scream

Thursday, January 5, 2012

Juventus - Black Night, White Light

As the Italian league entered its winter break, Juventus could look back on a highly successful campaign so far. Not only were they were joint leaders along with Milan, but they were the division’s only undefeated team, having won nine and drawn seven of their matches. In their best start for many years, the bianconeri have beaten both of their rivals from Milan and look poised for a return to their former glories.

Juventus have won a record 27 domestic league titles, not including two that were lost after the events of the 2006 Calciopoli match-fixing scandal, and have triumphed six times in Europe (two Champions League, three UEFA Cups and one Cup Winner’s Cup), so the current team has a long way to go before it can be mentioned in the same breath as its illustrious predecessors, but the early signs are promising.

However, nobody is taking anything for granted in Turin, especially as Juventus also started well last year before fading badly over the second half to finish seventh for a second successive season, which meant that they failed to qualify for Europe. In fact, by their own lofty standards, this has been a particularly barren period for Juventus, as they have not won a trophy for five long years.

"Conte - Shout to the top"

This season somehow feels different following the appointment of former Juventus captain Antonio Conte, who replaced Luigi Delneri in May. Although relatively inexperienced at the top level, Conte has managed to lead two clubs (Bari and Siena) to promotion to Serie A. Described by president Andrea Agnelli as “the first piece in the jigsaw to return to winning ways”, Conte has “brought a new mentality to the club”, according to the tenacious midfielder Claudio Marchisio.

The emphasis is on the team with every player working his socks off, though Conte has also impressed with his willingness to change tactics depending on the opposition. Although he is famed for his intense, attacking style, the young manager has also tightened up his side’s defence, largely with the same personnel as last season.

That said, there has been a lot of activity in the transfer market with general manager Beppe Marotta responsible for a major overhaul of the playing squad since his arrival from Sampdoria in May 2010. Although the club’s fans may have been disappointed that no major star arrived this summer after talk of Sergio Aguero, Giuseppe Rossi and Alexis Sanchez, this was compensated by the arrival of some very capable players.

"Lichtsteiner - Run, Forrest, run"

Midfield experience was recruited in the shape of Andrea Pirlo from Milan and Michele Pazienza from Napoli, while the exciting young Chilean Arturo Vidal from Bayer Leverkusen has provided much energy to the engine room. The weakness at full-back was addressed by the signing of the athletic Swiss Stephan Lichtsteiner from Lazio, while Mirko Vucinic from Roma has added some attacking guile.

The other major change this season has been the new stadium, where the fans are much closer to the action and can provide the proverbial 12th man. It is not clear how many points this has been worth to Juventus, but their record at home since the move has been strikingly good.

So this is in many ways a “Newventus”, but there are still a few important links to the club’s past. In the dressing room, this is provided by club captain, Alessandro Del Piero, who is in his final season, while the Agnelli family has long played an important custodial role. Andrea’s late father Umberto was also president between 2003 and 2005, while his uncle Gianni (“l’avvocato”) is a legendary figure at the club.

Although Juventus have shown a significant improvement on the field of play, it’s a different story off the pitch, as they reported a huge loss of €95 million for the 2010/11 season, a dramatic worsening from the previous year’s €11 million loss, when the club actually made a small €2 million profit before being hit with a hefty €13 million tax charge.

Unsurprisingly, this is the largest loss in Juventus’ history and it was described as “intolerable” by Agnelli, though he did add that these accounts were “the fruit of a desire to maintain Juve’s competitiveness.” That’s a fairly standard excuse from a director of a football club, but in fairness Juventus have paid the price for their attempts to transform the club, both through the investment in the new stadium and particularly the many changes on the staff side.

Up to this year’s annus horribilis, Juventus had made a pretty good job in balancing their books, recording profits before tax in three of the preceding four years, even when they were demoted to Serie B in 2006/07. That year, they were forced to offload many players in order to trim the wage bill, which also had the benefit of delivering outsize profits on player sales of €40 million.

"Marchisio - Black & White Boy"

Last season this activity produced €17 million profit, which is lower, but still not too bad. The real damage was done at the operating level, largely due to expenses of €195 million being considerably higher than revenue of €154 million, leading to negative EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxation, Depreciation and Amortisation) of €41 million, which was exacerbated by very large non-cash flow expenses of €61 million.

On the face of it, these are indeed disastrous figures, but a closer analysis of the reasons for the increase in the size of the loss provides some cause for optimism, as much of it is due to once-off factors that should not be repeated to the same extent in future years.

Of course, there are also some fundamental factors behind the larger loss, most notably the double whammy in television income, which has dropped by €43 million from €132 million to €89 million. The reduction was split evenly (more or less) between the move to a centralised sale of Italian TV rights and the failure to qualify for the Champions League, which was only very slightly offset by participation in the Europa League group stage.

Although total wages slightly increased by €2 million to €140 million, the underlying player wage bill was actually cut by €9 million, which was disguised by a €3 million rise in bonus payments and higher leaving incentive, which grew €8 million from €4 million to €12 million, thanks to pay-offs to Mauro Camoranesi, David Trezeguet and Jonathan Zebina in order to get them off the payroll.

Other once-off staff costs include a €6 million increase in the write-down of player values from €6 million to €12 million, partly for players that have already left (Tiago and Zdenek Grygera) and partly for those who no longer figure in the club’s plans (Amauri). There is also a €12 million provision for dismissed staff and a €12 million increase in the cost of purchasing temporary player rights from €3 million to €15 million (mainly Quagliarella €4.5 million, Pepe €2.6 million, Matri €2.5 million and Marco Motta €1.3 million).

Exceptional items have increased by €10 million year-on-year, as last season’s €3 million credit for the transfer of the commercial area around the new stadium has been replaced by a €7 million provision for a tax inspection for the years between 2001 and 2008. Finally, it should be noted that the 2011 figures were “boosted” by the tax charge being €11 million lower than the previous year.

All in all, this set of accounts represents a classic example of a company cleaning house, so it would be surprising if the expenses were as high the next time around, even though there may still be a few once-off charges to process.

Of course, most football clubs do make losses and Italy is no exception, e.g. in 2009/10 (the last year when we have published accounts for all the clubs), only four clubs in Serie A managed to break-even: Fiorentina €4.4 million, Catania €2.5 million, Livorno €1.8 million and Napoli €0.3 million.

So, it is perfectly understandable that Juventus made a loss, but it is the sheer size of the loss in these accounts that came as a bolt from the blue, especially as over the previous two seasons (2008/09 and 2009/10) Juventus had looked like a good example of sustainability with aggregate losses of just €4 million. That was a drop in the ocean compared to the losses suffered by the other big clubs in the same period: Milan €77 million and Inter (an astonishing) €223 million.

However, the tables have well and truly turned and it is now Juventus that have the dubious honour of the highest loss in Serie A in 2010/11 with their €95 million surging ahead of Inter €87 million and Milan €70 million.

Much of this unfortunate reversal is clearly due to the steep revenue reduction. In 2009/10 Juventus’ revenue of €205 million was not far behind Inter’s €225 million, about the same as Milan’s €208 million and importantly comfortably ahead of all other Italian clubs with Roma the next closest with just €123 million, but this was no longer the case in 2010/11. In particular, Roma’s revenue of €144 million, aided by their Champions League run, was only €10 million below Juve’s €154 million.

This will also impact Juve’s seat at Europe’s top table. In 2009/10 they were placed tenth in Deloitte’s European Money League, which would be the envy of many clubs, but is a long way short of their peers abroad. For example, the Spanish giants, Real Madrid and Barcelona, generate around €400 million, which is twice as much as Juventus, as they continue to benefit from substantial individual TV deals.

Both Manchester United and Bayer Munich also earn around €100 million more, the English taking advantage of significantly higher match day revenue, while the Germans’ commercial expertise puts Italian clubs to shame. This vast revenue discrepancy will make it difficult for Juventus to achieve their stated objective of “being a leading club in Europe”. Indeed, the revenue reduction in 2010/11 is likely to mean that they will fall out of the top ten in next year’s Money League.

Juve’s challenge is not helped by the underlying problems in Italian football. Andrea Agnelli went so far as to complain of “a penalising regulatory situation for the top teams in Italian football” where government regulations were “to the detriment of investment.”

His views were supported by a report from the Italian Football Federation (FIGC) this year that concluded, “The current business model is difficult to sustain and not very competitive.” Its president, Giancarlo Abate, noted that in particular match day income, sponsorships and merchandising were in need of urgent attention to reduce the reliance on TV money. Juve’s courageous move to construct a new stadium is very much the exception to the rule with other clubs’ revenue growth potential significantly restricted by the fact that their grounds are owned by the local council (to whom they have to pay rent).

These problems have been reflected in the lack of revenue growth of Italian clubs. In 2005 Juventus were as high as third in the Money League, but their revenue has actually declined by 33% (€75 million) since then. Milan’s revenue also fell during that period, while Inter’s growth of 32% is less than half that achieved by other leading European clubs, e.g. Barcelona 115%, Manchester United 99%, Arsenal 96%, Real Madrid 74% and Bayern Munich 69%.

Even more striking is the absolute difference between the clubs. As an example, in 2005 Juventus’ revenue of €229 million was around €20 million better than Barcelona, but it is now nearly €300 million less. In fact, this year’s revenue is only 9% higher than they generated in Serie B in 2006/07 (lower if you include profit on player sales).

The reality is that Juve’s revenue has essentially been flat for many years, only really growing when they qualify for the Champions League. The driver for the investment in a new stadium is obvious when looking at the club’s revenue mix, which shows match day income at a pitiful 8% of total revenue. That is by far the lowest of any team in the top 20 clubs in the Money League with the next lowest being the other Italian clubs (Milan 13%, Roma 16% and Inter 17%).

In 2009/10 Juventus earned an impressive €110 million from their domestic TV rights deal, which was the highest in Italy, even more than Milan €96 million and Inter €89 million, and considerably more than all other Italian clubs, e.g. Napoli, Lazio and Fiorentina only got around €40 million, which was just over a third of Juve’s income.

Years of protest at this lack of a level playing field finally led to a new collective agreement being implemented at the beginning of the 2010/11 season. There is a complicated distribution formula, which still favours the bigger clubs, though the result is a clear reduction at the top end. Under the new regulations, 40% will be divided equally among the Serie A clubs; 30% is based on past results (5% last season, 15% last 5 years, 10% from 1946 to the sixth season before last); and 30% is based on the population of the club’s city (5%) and the number of fans (25%).

Juventus had forecast that this would result in a revenue reduction of €9 million in a presentation to analysts in March 2011, but, as they admitted in the latest accounts, there was “an additional penalisation compared to what was expected” and the actual difference was a massive €23 million.

There has been much discussion over how the number of fans (worth 25% of the deal) would be calculated, but this was resolved in November. An article in La Gazzetta dello Sport suggested that this would produce an additional €4 million revenue for Juventus, but the net reduction would still be a painful €19 million.

The decrease would have been even higher if the total money negotiated in the new collective deal by media rights partner Infront Sports had not been approximately 20% higher than before at around €1 billion a year. This cemented Italy’s position as the second highest TV rights deal in Europe, only behind the Premier League, but significantly ahead of Ligue 1 and La Liga. In fact, Italy’s deal is worth twice as much as the Bundesliga.

That’s particularly impressive, given how little is received for foreign rights, though it was recently announced that the incumbent rights holder, MP & Silva, will pay an additional 30% for these rights for the three years starting from the 2012/13 season (up from €90 million a year to €115-120 million). It is still not completely clear what will happen with the 2013-15 deal for domestic rights, but €2.5 billion has already been secured from Sky/RTI for 12 of the 20 Serie A clubs, so this is likely to show a small increase as well.

One of the key risks identified in the Juventus annual report is failure to qualify for the Champions League, which “could potentially have an adverse impact on the company’s financial position and income statement.” In truth, there’s no doubt about this, e.g. in 2010/11 Juventus earned just €1.8 million from the Europa League, while the previous season they received €21.5 million from their adventures in the Champions League, leading to a €20 million fall in revenue.

The prize money for Europe’s flagship tournament increased last season, so Roma received €30 million for reaching the last 16, while Inter got €38 million for going a round further. The same is true for the Europa League, but the highest pay-out there was only €9 million. Those are just the television distributions, but there are also additional gate receipts and bonus clauses in various sponsorship deals.

Juve’s failure to qualify for this season’s Champions League will again hurt them financially, which is why it is imperative that they achieve that goal this time around. Unfortunately, their task is even more difficult now, as the Italian league has lost a place to the Bundesliga, due to lower coefficients. From this season, only the top two teams in Serie A will be assured of direct entry, while the third-placed team goes into the preliminary qualifying round. Ironically, this has been Italy’s best season in the Champions League for a while with three teams reaching the last 16 (Milan, Inter and Napoli).

Although the most popular club in Italy, Juventus have struggled to convert this support into meaningful match day revenue. This is an issue for all Italian clubs, but especially Juventus, where this revenue stream fell from €17 million to €12 million last year, largely due to €3.2 million lower fees from friendly matches. This is just behind Roma’s €19 million, but is far below Inter (€33 million) and Milan (€31 million), who generate much more revenue at San Siro.

The comparison is even worse when looking at leading clubs abroad, which is perhaps best illustrated by a comparison with Manchester United and Arsenal, who earn €126 million and €108 million respectively. This works out to around €4 million revenue a match, which is over ten times as much as Juventus (€0.4 million).

Not only do Juventus have the lowest average attendance of the top European clubs in the Money League at around 22,000, partly because many of their fans are located in the south of Italy, but this was only the 10th highest in Serie A last season, lower than clubs like Palermo and Genoa. In comparison, Inter’s average crowd was over 58,000, while Milan and Napoli averaged 50,000 and 45,000 respectively.

Of course, Juventus were limited by the capacity of their old ground, which was very low at 28,000, and this also suffered from having hardly any premium seats or corporate boxes, which are the money spinners elsewhere. This is why Juventus decided to move to a new stadium that could maximise their revenue earning potential.

A splendid inauguration ceremony took place on 8 September including a friendly match against Notts County, the team who gave Juventus their famous black and white striped shirts in 1903. The new 41,000 capacity stadium has been built on the site where the reviled Stadio Delle Alpi once stood and features 8 restaurants, 24 bars and 4,000 parking places.

"All my colours"

The atmosphere and visibility are far superior to the old ground, as the closest seats are just 7.5m from the pitch. Although not as large as some modern stadiums, chief executive Aldo Mazzia explained, “We believe that it’s better to have a stadium that’s a bit smaller but almost always full and closer to the team than to have a much bigger one that only gets sold out for a few games.” Indeed, every game to date has been a sell-out, though there have been quite a few empty seats, due to ticket agencies unable to fully sell their allocation.

The cost has increased to €150 million, including €15 million for the Juventus Museum that is scheduled to open in the first half of 2012, but it has largely been financed by two important initiatives.

First, Sportfive acquired the stadium naming rights for a guaranteed minimum of €75 million, of which €42 million has already been paid to the club and the remaining €33 million will be paid over the next 12 years in equal annual installments of €2.75 million. From 2011/12, this will be booked as €6.25 million annual revenue. Although a sponsor has yet to be identified, this is only an issue for the broker and does not affect Juventus financially. Second, Juventus sold the commercial land adjacent to the stadium for €20 million to Nordiconad, who will build a shopping area called Area 12.

"Money don't Matri 2 night"

This meant that Juventus only had to take on additional debt of €60 million, which was provided by Istituto per il Credito Sportivo. As at 30 September 2011, €52 million of this had been loaned to the club.

The new stadium looks the business in both senses of the word, as it will be a seven-day a week operation, hosting numerous events and guided tours of the museum. Indeed, the club has estimated that match day revenue will increase significantly from the current €12 million to €25-35 million, with the number of premium seats being particularly important, e.g. Arsenal make 35% of their match day revenue from just 9,000 premium seats at the Emirates.

The first quarter results for 2011/12 support these claims, as the number of season tickets rose by 61% to 24,137, which is impressive enough, but the revenue increased by 183%. Although there have been some teething troubles with the safety inspections, Mazzia predicted that the new stadium would give it a competitive advantage over its Italian rivals of “at least four or five years”, which makes sense if you consider that Juventus signed their stadium agreement with the city of Turin way back in July 2003.

Commercial revenue is not too bad at €54 million, though it is €2 million lower than 2009/10, mainly due to performance clauses linked to Champions League participation. In Italy, Inter have now caught up, while Milan still do better commercially. Perhaps of more relevance is the fact that Juventus are a long way behind leading clubs abroad, e.g. Bayern Munich earn an astonishing €173 million.

This is one of the problems of being tainted with Calciopoli, as Juve’s commercial income has not yet reached the heights they achieved before those events (€75 million in 2006). In 2005 Tamoil signed a five-year shirt sponsorship deal that was believed to be the highest in football history at €22 million a season with a possible five-year extension worth even more. This was more than twice the size of any other deal with an Italian club, but was cancelled in the light of the scandal.

These days, Juventus have adopted an innovative dual shirt sponsorship strategy with BetClic paying €8 million for the first team shirt and Balocco €3.5 million for the second shirt and youth sector. Both of these deals are in their last season, so there is an opportunity to sign better deals, though Juventus have cautioned that the “current economic situation has a negative impact on the sport sponsorship market.” In contrast, the long-term partnership with kit supplier Nike has been extended until 2015/16 for an impressive €12.4 million a year.

On the plus side, Juventus’ sponsorship deals compare favourably with those at other Italian clubs: (a) shirt sponsors: Milan – Emirates €12 million, Inter – Pirelli €12 million, Napoli – Lete €5.5 million and Roma – Wind €5 million; (b) kit suppliers: Milan – Adidas €13 million, Inter – Nike €12 million, Roma – Kappa €5 million and Napoli – Macron €4.7 million.

However, the issue is that these agreements are worth much less than those at foreign clubs. For example, the following all have shirt sponsorships worth more than €20 million a season: Barcelona, Bayern Munich, Manchester United, Liverpool, Manchester City and Real Madrid.

Like all football clubs, the most important expense for Juventus is their wage bill, which was €140 million in 2010/11, split between players €127 million and other personnel €13 million. They have admirably managed to hold this at around the same level for the last three years. In fact, last season they actually cut underlying player wages by €9 million, though this was off-set by leaving incentives.

Nevertheless, the important wages to turnover ratio has worsened from 67% to 91%, due to the substantial revenue reduction. This takes it way above UEFA’s recommended upper limit of 70%, so Juve need to either grow revenue or cut costs.

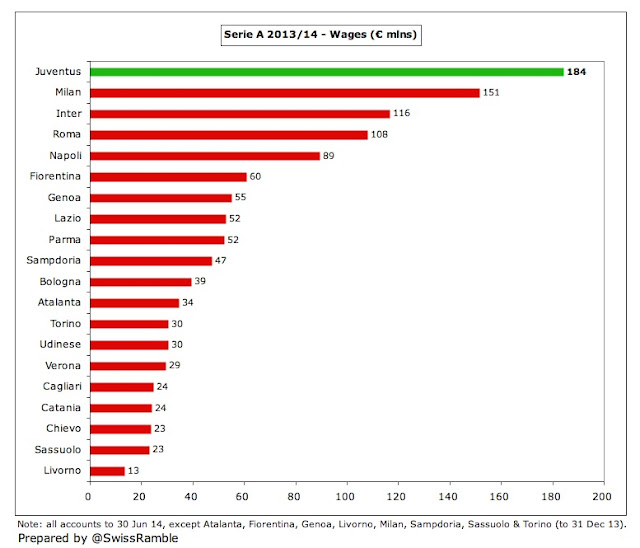

Despite their efforts, their wage bill remains one of the largest in Italy, albeit a long way behind Milan and Inter, who cut theirs to “only” €190 million in 2010/11, thanks to lower performance bonuses. An analysis by La Gazzetta dello Sport this summer of salaries for the first team squad reinforced Juve’s third place in the wages league with €100 million, behind Milan €160 million and Inter €145 million, but it’s far from certain that their figures are accurate.

The other major element of player costs, namely amortisation has been on a rising trend, up from €22 million in 2007 to €35 million in 2011, though it is still less than the €52 million reported by Inter last season.

Amortisation is the annual cost of writing-down a player’s purchase price, which is booked evenly in the accounts over the length of his contract, e.g. Milos Krasic was signed for €16 million on a 4-year contract, so his amortisation works out to €4 million a year.

The growth in amortisation would imply that Juventus have been active spenders in the transfer market and this is indeed the case. Apart from the year that they were relegated to Serie B, they have been very much a buying club. In fact, over the last three seasons their net transfer spend of €129 million is the highest in Serie A with only Napoli coming anywhere close with €98 million. The next highest is Roma with €35 million, while both Inter and Milan have actually had net sales proceeds in this period.

This summer alone they splashed out nearly €90 million, though €37 million of that was due to exercising options on players such as Matri €15.5 million, Quagliarella €10.5 million, Pepe €7.5 million and Motta (yes, really) €3.75 million. In addition, large sums were spent on Vucinic €15 million, Vidal €10.5 million, Lichtsteiner €10 million and Eljero Elia (from Hamburg) €9 million.

This was part of what the club has described as the “profound upgrading of the first team” in order “to return as soon as possible to stably competing at a high level in Italy and Europe.” However, Beppe Marotta has warned that the club will not be making any big money signings in the January transfer window, which probably explains the loan signing of wayward striker Marco Borriello from Roma, though there have been faint whispers of Carlos Tevez arriving from Manchester City.

This high level of transfer activity has contributed to an increase in Juve’s debt, though the main reason is obviously the investment in the new stadium. For the last few years, the club’s focused approach meant that it actually enjoyed net funds, but financial debt was up to €121 million at the 2011 year-end. This comprised €61 million bank loans, €45 million of stadium debt to ICS (a 12-year loan at 4.383%) and €18 million of finance leases to Unicredit (mainly for the Vinovo training ground).

The financial position would have been worse without the phased payment of transfer fees, which means that Juventus owe other football clubs €63 million (though they are, in turn, owed €33 million by other clubs).

That said, they did improve their net debt by €25 million in the first quarter of 2011/12, largely thanks to a €72 million advance payment by Exor, their 60% majority shareholder controlled by the Agnelli family, which was their share of the €120 million capital increase. Exor has also undertaken to pay €9 million corresponding to the rights of LAFICO (the Libyan Arab Foreign Investment Company), the club’s second largest shareholder with 7.5%, but whose stake has been frozen as a result of sanctions applied to the North African country.

The remaining €39 million should be covered by the other, smaller shareholders, though this will require an act of faith on their behalf, as the share price is less than half the €1.30 four years ago when the club launched a similar €105 million recapitalisation. Indeed, it was €3.70 when the company was floated back in 2001.

Assuming that the money is raised, Mazzia said that it would “finance the club’s life for the next five years”, though this must assume a return to a self-financing model. Although recent years have required two sizeable capital raisings and new loans, there have been special circumstances (Calciopoli and the new stadium), so this is not entirely unfeasible, though it will require improvements on the pitch.

However, it is likely that Juventus will still have to rely on the support of Exor, which has always been forthcoming, but their fortunes to a large extent depend on the performance of their other companies, notably Fiat, which is struggling along with all other car manufacturers.

The club’s balance sheet has been weakened by last year’s gigantic loss, so it now has net liabilities of €5 million, as opposed to the €90 million net assets the year before, though it should be acknowledged that player values in the accounts are certainly lower than their worth in the real world.

From now on, Juventus will also have to confront the challenge of UEFA’s Financial Fair Play (FFP) regulations, which will ultimately exclude from European competitions those clubs that fail to live within their means, i.e. make a profit.

Fortunately, the big loss in 2010/11 is not taken into consideration, so all those cost provisions begin to make sense. That said, UEFA will take into account losses made in 2011/12 and 2012/13 for the first monitoring period in 2013/14, so Juve’s accounts need to rapidly improve.

However, they don’t need to be absolutely perfect, as wealthy owners will be allowed to absorb aggregate losses (“acceptable deviations”) of €45 million, initially over two years and then over a three-year monitoring period, as long as they are willing to cover the deficit by making equity contributions. The maximum permitted loss then falls to €30 million from 2015/16 and will be further reduced from 2018/19 (to an unspecified amount).

Although Juventus’ stated plan is “to develop a sustainable business model”, they have also admitted that 2011/12 will show another “significant loss”, though not as bad as that reported last season. Worryingly, the €26 million loss for Q1 2011/12 was actually €8 million worse than the prior year, but that is largely timing, due to fewer games played.

In terms of how their figures will look in the future, the first thing to do is to adjust for all the exceptional items in 2010/11, which would have a €43 million positive impact. This assumes: (a) no further need for provisions for tax and dismissed staff; (b) reducing (but not eliminating) charges for player write-downs, leaving incentives and temporary purchases to more normal levels.

Aldo Mazzia has stated that the revenue from the new stadium will increase to €32 million, including the doubling of gate receipts and €6 million for naming rights. This would deliver an additional €20 million revenue, though there will also be a rise in associated costs, such as new staff. In addition, the club will have to bear depreciation on the stadium investment and interest on the loans, though these are excluded for the purposes of the FFP break-even calculation.

"Vidal - Ears are not enough"

Of course, the major swing factor is qualification for the Champions League, which would be worth around €30 million, maybe more depending on progress. This helps explain the heavy investment in the playing squad, which can be considered a bet on success.

It is difficult to speculate on what will happen to the wage bill. My analysis of the arrivals and departures, based on the gross salary figures published in La Gazzetta dello Sport, suggest that there will be a small fall next year, but it is safer to assume the same level. On the other hand, player amortisation is almost certain to increase (€3 million in Q1), so I have assumed €10 million per annum. In addition, if the club qualifies for the Champions League, then bonuses should rise to previous levels, meaning an increase of €8 million.

Profit on player sales is by its nature lumpy business, but Juventus have been fairly consistent over the past four years, generating €14-17 million a season. It is therefore reasonable to assume that they will produce similar sums in future, though they might struggle to match this in 2011/12, as they reported less than €6 million from the summer transfer window. They might add to this in January, perhaps with the departures of the out-of-favour Krasic and Amauri.

All those adds and drops would produce a far more palatable loss of €18 million, which would be well within the FFP acceptable deviation. For the purposes of FFP, UEFA also exclude some expenses that are considered to represent positive investment, such as youth development (€6 million per the analysts’ presentation) and community (estimated at €2 million), which would bring the figure down to a €10 million loss.

There is yet another get-out clause in UEFA’s regulations that states that clubs will not be sanctioned in the first two monitoring periods, so long as: (a) the club is reporting a positive trend in the annual break-even results; and (b) the aggregate break-even deficit is only due to the 2011/12 deficit, which in turn is due to player contracts undertaken prior to 1 June 2010.

Although the estimates above are by no means a fait accompli, if Juventus do get reasonably close to those figures, my guess is that UEFA would look favourably on their finances, as they would clearly be moving in the right direction and setting the right example.

"Celebrate!"

This is further evidenced by Juventus’ focus on the youth sector, as seen by the money spent on the training centre. The results are clear to see with all but one of their youth teams leading their respective leagues at the end of 2011, including the important Primavera.

This investment is a sure sign that this is intended to be a long-term project. As Conte put it earlier this season, “After three months of work you cannot talk about a finished house with a roof ready.” The return to former glories is a long way off, but there is no doubt that Juventus have taken some important first steps on a long journey.