So, barring any problems with a medical, Zlatan Ibrahimovic will today sign for Paris-Saint Germain. Many in the football world have been shocked by PSG’s audacious €65 million swoop for the Milan duo of Ibrahimovic and Thiago Silva, but it really should come as no surprise given the club’s massive transfer outlay ever since it was purchased by Qatar Sports Investments (QSI) last summer.

In much the same way as Manchester City did when they signed Robinho after their Abu Dhabi takeover, PSG immediately made a resounding statement of intent when they shattered the French transfer record with the €42 million purchase of Argentine playmaker Javier Pastore from Palermo. They also scooped up the cream of French football, buying Ligue 1 leading scorer Kevin Gameiro and powerful midfielder Blaise Matuidi, while raiding Serie Afor Jérémy Menez (from Roma), Mohamed Sissoko (Juventus) and Salvatore Sirigu (Palermo), and securing the services of the Uruguayan captain Diego Lugano (Fenerbahce).

The spending did not stop there, as new manager Carlo Ancelotti brought in experience in the January transfer window in the shape of Thiago Motta (from Inter), Maxwell (Barcelona) and Alex (Chelsea). This summer, as well as Ibra and Silva, PSG have to date also splashed out €26 million for Napoli’s forward Ezequiel Lavezzi and €12 million for Pescara’s technically gifted young star Marco Verratti. There’s also talk that Kaká might join the French revolution.

QSI, an investment arm of Qatar’s sovereign wealth fund owned by the ruling Al Thani family, bought 70% of PSG from American investment company Colony Capital in May last year, before acquiring the remaining 30% in March in a transaction that placed a €100 million value on the entire club. Right away, they installed Nasser Al-Khelaifi as club president, banking on his sports experience from his role as director of the TV channel Al Jazeera Sports and president of the Qatar Tennis Federation.

"We'll meet again"

Al-Khelaifi spoke of his hopes for this sleeping giant, “It’s a big club with a history and super fans.” Indeed, PSG is only behind Marseille in terms of popularity in France. The year before, their potential had been underlined by no less a person than Arsène Wenger, “PSG is the only club in the world which is based in an area of 10 million inhabitants and doesn’t have any competition (from a rival club).” With spooky prescience, he added, “What needs to be done is to get a group of investors around the table to provide the club with some financial muscle.”

However, there is little doubt that they have been under-achievers since they were founded in 1970 after the merger of Paris FC and Stade Saint-Germain. In fact, they have not won the Ligue 1 title for 18 years, though in fairness they do hold the record for the longest current spell in the competitive French top flight without being relegated.

To an extent, QSI’s investment is nothing new under the sun for PSG. With obvious parallels to the current situation, they were bought in 1991 by TV channel Canal+, who proceeded to invest substantial sums in attracting players of the calibre of David Ginola, George Weah and Rai to Paris, leading to a glorious few years, when they reached a Champions League semi-final, two UEFA Cup semi-finals and two Cup Winners’ Cup finals, winning one of them in 1996 against Rapid Vienna and losing the other in 1997 to Barcelona.

"Ménez - Jérémy spoke in class today"

However, the club ran up huge losses and built up substantial debts, leading to the 2006 sale to Colony Capital (plus minority shareholders Butler Capital Partners, a French investment company, and Morgan Stanley, an American investment bank). On the plus side, this consortium wiped out the club’s debts, but against that they appeared more interested in the property development opportunities at the Parc des Princes stadium and the training centre at Camp des Loges. The supporters’ dissatisfaction with their approach was summed up by a banner unfurled at the ground a couple of years ago: “Colony: a great PSG or get lost.”

Those fans are unlikely to be disgruntled with the ambition shown by QSI, who have promised to spend €100 million a year for the next five or six years in order to build a strong team, before slowing down the investment. Although Al-Khelaifi claimed that this level of expenditure was “normal for a top-ranking club”, only Manchester City have really done anything similar for such an extended period.

The idea is “to invest a lot and immediately” with the objective of joining Europe’s elite. Al-Khelaifi emphasised the European aspirations, “Obviously everyone dreams of winning the league, but our priority right from next season is the Champions League.” As part of their five-year strategy, they hope to compete in the Champions League on a regular basis and be in a position to win the trophy in three years.

"Ancelotti - Hands off, he's mine"

Although PSG’s official statement on the QSI takeover included the usual, bland remarks about looking “to take the club to the next level”, Carlo Ancelotti was in no doubt about the new owners’ targets, “The aim of the club is very clear. They want to build a team to win in the Champions League, not just in France.”

Last season, PSG finished second in Ligue 1, which was enough to qualify them for the Champions League, though it must have been something of a disappointment for QSI, given last summer’s spending spree. Indeed, when PSG were leading the title race before Christmas, Al-Khelaifi said, “Given the league table at present, if PSG are not champions of France at the end of the season, it will be a failure.”

It must have been particularly galling that they lost out to Montpellier, a club whose entire annual budget of €33 million is less than the amount PSG paid for one player (Pastore). It would be small comfort to know that the French league is one of the most unpredictable around, having five different champions in the last five seasons.

Moreover, the club had sacked the unfortunate Antoine Kombouaré to make way for Ancelotti, despite the club stalwart guiding PSG to the top of the table, though his expensive team had just crashed out of the Europa League. The feeling was that Ancelotti was the right man to take the club forward, having won two Champions Leagues and Serie A with Milan plus the Premier League with Chelsea. In addition, his reputation would help PSG attract the calibre of player required to make that big jump in quality, though the high salaries on offer might also help and Paris is not exactly a hardship posting.

Off the pitch, there will be plenty of changes too, as PSG will rack up enormous losses. In fairness, the club has consistently lost money in the past few years, though these will pale into insignificance compared to what is about to hit their books.

In the last published accounts for the 2010/11 season, before the impact of the QSI takeover is considered, they made a tiny loss of €201,000, though this was heavily influenced by exceptional financial items of €27.9 million. These are not explained, though are probably due to movements in provisions, which was the case in 2009/10.

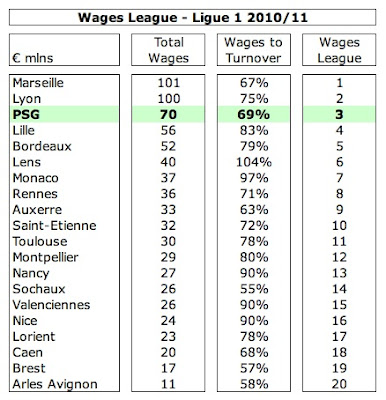

Excluding this adjustment, PSG’s loss would have been €28.1 million, even higher than the €21.9 million the previous season, which was the second highest in Ligue 1. The 2010/11 operating loss was essentially due to €130 million of expenses, including €70 million of wages, being far higher than the €101 million of revenue. Profit on player sales and interest payable were negligible.

In the previous five years, PSG’s loss averaged over €14 million a season, while the cumulative losses since 1998 add up to a colossal €300 million. In those 13 years, PSG have not once reported a profit.

In terms of Ligue 1 profitability, PSG were mid-table in 2010/11, but if the exceptional items were ignored, their underlying loss was about the same as Lyon’s €28 million, which was the worst in the league. This was a repeat of the previous season when Lyon (€35 million) and PSG (€22 million) also reported the largest losses.

The only other club that reported a double-digit loss in 2010/11 was Marseille with €15 million, while half of the 20 clubs were profitable. In fact, the total Ligue 1 losses of €46 million were much improved from the previous season’s €114 million, despite a 3% fall in revenue, as expenses were cut and profits from player trading increased – partly due to PSG’s purchases.

That’s all very well, but it will be a whole new ball game under QSI. The club had originally estimated a loss of €40 million for 2011/12, but this has been revised upwards to €100 million following the signing of new players, the hiring of new staff including Ancelotti and Kombouaré’s pay-off.

The plan for next season assumes a deficit of €70 million, based on €130 million revenue and €200 million expenses, comprising €120 million wages (60%), €40 million player amortisation (20%) and €40 million other expenses (€20 million). This is the first time that any French club’s budget has gone above €150 million and would mean combined losses over the next two years of €170 million, though even that may be under-estimated.

This is not a problem for the Direction Nationale du Contrôle de Gestion (DNCG), the organisation responsible for monitoring and overseeing the accounts of professional football clubs in France. In contrast to UEFA’s Financial Fair Play (FFP) regulations, they allow owners to dig into their pockets to cover shortfalls with their own funds and they are satisfied with the bank guarantees provided by PSG’s directors.

The DNCG president, Richard Olivier, explained their view, “The more famous players there are in L1, the more spectators there will be. The Qatari are great. They’re putting in €200 million and with them we can hope to gain the fourth place in UEFA’s coefficients. They’re filling the stadiums and bring money directly and indirectly.”

"Lavezzi - heading to Paris"

Of course, it’s a very different story with UEFA’s FFP, which will ultimately exclude from European competitions (Champions League and Europa League) those clubs that fail to live within their means, i.e. break even. In particular, clubs will not be allowed to make up for losses via handouts from the owners. The first season that UEFA will start monitoring clubs’ financials is 2013/14, but this will take into account losses made in the two preceding years, namely 2011/12 and 2012/13.

They don’t need to be absolutely perfect, as wealthy owners will be allowed to absorb aggregate losses (“acceptable deviations”) of €45 million, initially over two years and then over a three-year monitoring period, as long as they are willing to cover the deficit by making equity contributions. The maximum permitted loss then falls to €30 million from 2015/16 and will be further reduced from 2018/19 (to an unspecified amount).

In addition, UEFA’s break-even analysis allows clubs to exclude “good” costs, such as depreciation on fixed assets and expenditure on youth development and community, while the first year can deduct wages of players signed before June 2010.

That’s a help, but PSG’s projected losses of €170 million are clearly far higher than the €45 million allowance, so it looks like they will have to rely on one of UEFA’s get-out clauses, namely that an improving trend in the annual break-even results “will be viewed… favourably” (Annex XI). In this way, they might manage to avoid the ultimate sanction of being thrown out of the Champions League.

Indeed, while UEFA’s president Michel Platini has said that he is not a fan of clubs that “buy players left, right and centre”, Andrea Traverso, his head of licensing, has been more circumspect, “Before we apply any penalties, we will look at a club’s financial situation in its entirety.”

Nevertheless, Al-Khelaifi is well aware of this issue and has said that it is QSI’s long-term plan to make PSG into a profitable club, “In five years we want to make money.” The idea is to invest massively in new players in the first few years in order to boost the sporting and commercial potential of the club, so that it is self-sufficient by the time that FFP really begins to bite.

The impact of QSI’s arrival on the club’s activity in the transfer market has been dramatic. In the decade before the takeover, PSG’s net spend was just €27 million, but has been a remarkable €199 million since then. The director of football (and former PSG player), Leonardo, has said, “We want to do something long term and not buy ten Messis straight away. That’s not how you build a team”, but he added that the club was “obliged” to spend big sums if it wanted to compete at the highest level.

Evidently, they are following the playbook used by Chelsea and Manchester City, who spent massively in the first two seasons following the arrival of wealthy benefactors. Ancelotti has argued, “We don’t just want to spend for the sake of it”, though others might beg to differ, as the initial policy of buying proven domestic performers seems to have gone by the wayside in favour of international superstars.

This should lead to a significant competitive imbalance in France, as PSG have spent significantly more than the rest of Ligue 1 put together. The “closest” contenders to PSG’s €199 million net transfer spend since the QSI takeover are Rennes and Marseille, with just €16 million and €11 million respectively.

Not only that, but in that period PSG are the biggest spenders in Europe, ahead of Abramovich’s Chelsea (€127 million) and a rejuvenated Juventus (€117 million). No other club has spent more than €100 million in this period. Traditional powerhouses like Bayern Munich and Manchester United have been left in the shade, while the nouveaux riches clubs like Manchester City, Anzi Makhachkala and Malaga are also in PSG’s slipstream.

Up until the last accounts, PSG did a reasonably good job controlling their wage bill with their 2010/11 wages to turnover ratio of 69% being just within UEFA’s recommended upper limit of 70%. In the last five years, wages have grown in line with revenue, as both have risen around €20 million since 2006.

In fact, PSG only had the third highest wage bill in France of €70 million in 2010/11, a long way behind Marseille (€101 million) and Lyon (€100 million), though more than twice as much as Montpellier (€29 million), who went on to become champions the next season.

The gap to the leading European clubs was even more striking before the QSI takeover. The Spanish giants, Barcelona (€241 million) and Real Madrid (€216 million), had wage bills more than three times as much as PSG, while even the notoriously parsimonious Arsenal (€149 million) paid out twice as much. As an example of the impact of major squad investment, Manchester City’s wage bill has doubled in two years to €209 million.

These huge discrepancies help explain why PSG need to spend if they have any chance of breaking into this select group, though this will be even more of a challenge, given the high tax rates in France, which means they have to pay a higher gross salary than their competitors in other countries to ensure that the net salary is at the same level.

This is reflected in the salaries paid to the new recruits, which are as high as €4 million a year, according to a summary published by the Sportunewebsite (based on figures collected from Le Parisien and France Football) for the 2011/12 season. On top of that, Ancelotti is reportedly receiving €6 million a year, an unprecedented figure for a coach in France. The list adds up to €65 million, but that excludes other players, coaching staff, administration staff, social security and bonus payments, so the total wage bill was actually much higher.

Although reported figures for transfer fees and player salaries are notoriously inaccurate, we can still make a reasonable estimate of the increase in costs arising from the new signings since the 2010/11 accounts.

First of all, we need to understand how football clubs account for transfer fees. Instead of expensing these completely in the year of purchase, players are treated as assets, whereby their value is written-off evenly over the length of their contract via player amortisation. As an example, Kevin Gameiro was bought for €11 million on a four-year contract, so the annual amortisation is €2.75 million (€11 million divided by four years).

In this way, the cost of buying players (in accounting terms) is spread over a number of years, but the table above suggests that the incremental amortisation is about €53 million. Additional wages amount to €78 million, including €25 million for Ibrahimovic (gross cost for €14 million net salary), plus social contributions of a further €20 million, so the total increase in costs should be around €151 million. That enormous figure excludes bonus payments, so the actual rise will be even higher.

It also does not take into consideration the super tax proposed by incoming Socialist president, François Hollande, whereby all income above €1 million would be taxed at 75%, a huge jump from the current 41%. There is some doubt over whether that would apply to footballers, but if it did come into force, it would significantly increase the gross costs to a football club when a player’s contract has been agreed on a net basis. In this case, a French tax expert calculated that the total cost of Ibrahimovic’s mega contract to the club, including social security, would be an unbelievable €70 million.

"Come on, Alex, you can do it"

Obviously, some players have left PSG since 2010/11, including Ludovic Giuly, Gregory Coupet and Claude Makélélé (though he has remained at the club as assistant manager), but the impact on wages would be relatively small.

Clearly, there are other costs besides salaries and player amortisation, but these are by far the most important for a football club, so even with the caveats outlined above, the calculated €151 million increase should give us a good idea of the financial challenge facing PSG. If we add that to the underlying 2010/11 loss of €28 million, we get to a projected loss of €179 million for PSG in 2012/13, which is a lot higher than the club’s budgeted loss of €70 million for that season. The only way that could be reduced is by growing revenue; so let’s explore the possibilities there.

QSI’s plans involve growing revenue from the current €101 million to €130 million in 2012/13 and then to €250 million in 2014/15 – a substantial increase by anybody’s standards. They have a four-pronged strategy to turn PSG into a leading global brand: (a) sporting success – reflected in higher TV revenues from Ligue 1 and the Champions League; (b) gate receipts – higher crowds paying higher ticket prices; (c) sponsors – a significant increase in the amounts paid by each sponsor; (d) merchandising – shirt sales off the back of superstars like Pastore and Ibrahimovic.

PSG’s current revenue of €101 million is the third highest in France, though it is a fair way behind Marseille (€151 million) and Lyon (€133 million). On the other hand, it is significantly higher than Lille, the fourth placed club, whose revenue is €34 million lower. It is again striking that the 2011/12 champions Montpellier had revenue of just €37 million.

Interestingly, PSG has the lowest reliance on TV with that category accounting for 44% of the club’s total revenue, though that is partly due to the lack of Champions League. Against that, they had the highest proportion from match day (18%) and second highest from commercial (38%), only behind Monaco.

Although PSG are not mentioned in Deloitte’s annual money league, their revenue would place them 22 nd in the list, just behind Benfica, and about the same level as Aston Villa. Their stated target of €250 million would give them the same revenue level as Arsenal and Chelsea, taking them into the top five, which demonstrates the extent of their ambition – or, alternatively, how difficult it will be to achieve this goal.

The last season that PSG’s revenue grew substantially was 2008/09, when it rose €28 million from €73 million to €101 million, which was because of two main reasons: (a) success on the pitch – higher league place and progress in the UEFA Cup, which resulted in higher TV revenue (aided by a slightly higher new French TV deal) and gate receipts; (b) different accounting for Nike merchandising – previously the club had only reported net royalties, but from 2009 they included gross revenue (around €8 million) with a similar increase in expenses.

Excluding those factors, annual revenue between 2006 and 2010 averaged around €80 million, though 2011 climbed to €101 million, largely due to television revenue, arising from Europa League participation and a higher position in Ligue 1.

The distribution model for French TV money is relatively equitable with 50% allocated as an equal share, while the remainder is distributed based on league performance 30% (25% for the current season, 5% for the last five seasons) and the number of times a team is broadcast 20% (over the last five seasons). This resulted in €43 million for PSG in 2011/12, €4 million higher than 2010/11, essentially due to finishing higher in the league.

There had been concern that the new four-year TV deal starting in 2012/13 would be considerably lower than the current deal, as one of the existing broadcasters, Orange, decided to withdraw from the bidding process, leaving Canal+ as the only game in town. However, Al Jazeera, whose director is the very same Al-Khelaifi that is president of PSG, helpfully stepped into the breach to take some of the packages, while strengthening their position in French football.

Although this has prevented a financial calamity for many French clubs, who are very reliant on TV money, it should be noted that the annual €610 million from the new deal is still lower than the current €668 million, though their president considered this to be “more than satisfactory in the current economic climate.” That said, Al Jazeera also picked up international rights for six years for €192 million, which works out to €32 million a year, nearly 70% higher than the current €19 million – though that is surely still a bargain, given the stars that are being attracted to PSG.

This is in stark contrast to the Premier League, where the new three-year domestic deal has increased by an amazing 70% to €1.3 billion a year, while the overseas rights are currently worth €0.8 billion a year (and likely to increase). The new French deal means that PSG’s revenue growth possibilities here are extremely limited for the next four years, leaving their TV revenue much lower than their competitors abroad.

If we compare PSG’s TV revenue for Ligue 1 of €43 million with the top two clubs in other major leagues, we can see the problem. Real Madrid and Barcelona earn nearly €100 million more a season from their lucrative individual deals, while the Italian clubs generate around twice as much even after their return to a collective deal. The two Manchester clubs receive €30 million more a year, while even the club finishing bottom in last season’s Premier League, Wolverhampton Wanderers, got €6 million more than PSG with €49 million.

Where PSG could grow their revenue is regular participation in the Champions League. Last season the three French clubs earned an average of €22 million (Marseille €27 million, Lille €20 million and Lyon €19 million), compared to PSG’s paltry €2.4 million from the Europa League. The amount earned is partly due to performance and partly an allocation from the TV pool, where half is based on progress in the current season’s Champions League and half on the previous season’s Ligue 1 finishing place (first club 50%, second 35%, third 15%).

Handily for PSG (and other French clubs), the amount paid to screen the Champions League in France has doubled for the three years from 2012/13, largely thanks to the intervention of (yes, you guessed it) Al Jazeera, who paid €180 million for that majority of the rights with Canal+ picking up the rest. This should mean that TV pool money will double from next season, so PSG can expect to collect around €28 million (and more if they progress beyond the group stage).

There is also plenty of room for growth in match day income. Although PSG’s €18 million is not too bad for France, it is miles behind Europe’s finest, e.g. Real Madrid, Manchester United, Barcelona and Arsenal all generate more than €100 million. PSG will be looking at many ways to (partially) close the gap: boost attendances, raise ticket prices and a better revenue mix (i.e. more premium customers, executive boxes, etc).

The new administration has already made much progress in attracting more crowds, with the average attendance rising an impressive 50% last season from 29,300 to 43,000 and many games being sold out. Admittedly, the previous season had seen a large decline from 35,100 due to former president Robin Leproux’s anti-hooliganism crackdown, following a number of incidents culminating in a death of a PSG supporter. This move towards a “broad family-based audience” initially saw a reduction in the number of attendees, but has now paid off, though the crowd is more gentrified these days. QSI’s ambitious target is to increase the number of season tickets to 40,000 from the current level of around 20,000.

At the same time, PSG will look to increase ticket prices (20% for the 2012/13 season), even though an analysis of the 2010/11 figures suggests that they are already the highest in France. There is a limit to how much the average fan is willing to pay, even when the football on offer is improving, so it will be imperative for PSG to find clever ways to maximise revenue from their premium customers. This can contribute a disproportionate amount of revenue, e.g. Arsenal make 35% of their match day revenue from just 9,000 premium seats at the Emirates stadium.

PSG currently play in the 48,000 capacity Parc des Princes, owned by the council, though they will have to play two seasons (2013/14 and 2014/15) at the nearby 81,000 Stade de France, as their current stadium needs to be renovated for Euro 2016. Although the local authorities have stated that PSG will return to the Parc des Princes for the long-term, there is a belief that PSG would prefer to build a new stadium, maybe on the same site, in a bid to emulate the revenue success of clubs like Bayern Munich and Arsenal, though that would be a longer-term project.

If PSG are going to have any chance of reaching their €250 million revenue target by 2014/15, they are going to have to get most of it from commercial activities. Although their current revenue of €38 million is again pretty good for a French club, it is a lot lower than Europe’s leading clubs with Bayern Munich (€178 million) and Real Madrid (€172 million) earning nearly five times as much as PSG.

They have hired Jean-Claude Blanc, former club president at Juventus, as chief operating officer in order to boost commercial revenue. As a first step, they have terminated the ten-year contract with sports marketing agency Sportfive, so that they can handle negotiations in-house. The strategy will essentially be to have fewer partners, who will pay more.

Long-term shirt sponsor Emirates pays €3.5 million a year in a deal extended to 2014, while Nike reportedly pays €6 million a season. PSG will look to increase each of these to €15-20 million per annum when they are up for renewal, which would be in line with the money earned by the big hitters, e.g. Manchester United receive €25 million from Aon’s shirt sponsorship and €32 million from Nike’s kit supplier deal.

In a sign of things to come, PSG dropped Winamax, as they do not pay enough, while they have signed up Qatar National Bank, who are reportedly paying €2-3 million a season just for a branding presence in the stadium. Some have speculated that his may be paving the way to them becoming main shirt sponsors, as their two-year deal ends at the same time as the Emirates’ contract finishes

Merchandising revenue should also significantly grow, particularly from shirt sales following the influx of top talent. Indeed, Al-Khelaifi said that shirt sales increased by 180% last year. That said, the amount of money earned per shirt is relatively small, so they will have to sell an awful lot to make a meaningful difference on their revenue. According to Nike and Adidas, the top selling clubs are Real Madrid and Manchester United – and even they “only” sell 1.2-1.5 million shirts a year.

Amusingly, the club’s commercial income actually includes a public subsidy. Although this has been cut from €2.3 million in 2008 to €1.25 million in 2012, many are unhappy that mega-rich PSG should continue to benefit from this funding.

"Gameiro - we need to talk about Kevin"

One possibility for PSG would be a mega sponsorship deal, similar to the one Manchester City signed with Etihad for a reported €50 million a year, which included stadium naming rights (even though City do not actually own their stadium). Here, PSG would have to be careful not to fall foul of UEFA’s FFP regulations, which specifically outlaw outrageous deals from “related parties”, so if QSI paid €100 million a season for a super-VIP executive box, this would be adjusted down to “fair value”.

PSG are also likely to make more money from player sales (only €2 million in 2010/11), as they will have to move on players that have lost their place following the new arrivals with candidates including the likes of Mamadou Sakho, Nenê and Clément Chantôme.

Now that we have reviewed PSG’s revenues and costs in detail, we can try to project PSG’s loss for 2012/13. Bearing in mind all the usual health warnings about forecasts never being 100% accurate, this should give us an indication of whether they are close to their target.

Taking the negligible 2010/11 loss as a starting point, we make an adjustment to remove the exceptional financial items, giving a “real” loss of €28 million. As calculated above, the new signings increase costs by €151 million for wages (including social security) and player amortisation. This would be offset by some departures, though given the relatively low salaries paid before the takeover, this would be a small amount, say a €10 million reduction. We should include a nominal €10 million for additional bonus payments, though this might be on the low side.

For revenue, let’s make a few extravagant assumptions. First, PSG will win Ligue 1, so their revenue will rise to €46 million, which is €7 million more than they received in 2010/11. They will also reach the quarter-finals of the Champions League, as Marseille did last year, so will receive €38 million (after the increase in TV rights), which is €34 million more than the €4 million they received from the Europa League in 2010/11.

Following the growth in attendances and higher ticket prices plus more attractive Champions League matches, we’ll go for a gutsy 100% increase in match day revenue, producing an additional €18 million. Similarly, we’ll assume a 50% increase in commercial income, worth an extra €19 million. In the long-term, PSG should earn considerably more here, but they are constrained in the short-term by existing contracts. For good measure, we’ll assume that they can make €10 million more profit on player sales.

"A whole Motta love"

All of that gives us a projected loss of €92 million, which is not too far away from PSG’s budgeted €70 million, but this estimate does include some fairly aggressive assumptions regarding revenue growth. In any case, it is clear that PSG will have to be very persuasive in their FFP discussions with UEFA about how their “project” will ultimately deliver more revenue and help them towards the elusive break-even point.

They would do well to emphasise their investment in PSG’s academy with so much of France’s football talent coming from the Paris area. Historically, this has been under-exploited by PSG, but there have been encouraging signs at both under-19 and under-17 level in recent seasons.

Of course, QSI’s acquisition of PSG is part of a broader strategy for Qatar to use the riches accrued from their vast reserves of natural gas to gain more influence on the global stage. Sport is the ultimate instrument for gaining “soft” power, especially football clubs. Thus, another Qatari investor has bought the Spanish club Malaga, while the Qatar Foundation paid a hefty €170 million to be Barcelona’s first ever shirt sponsor.

"Sirigu - back of the net"

There are also strong trading links between France and Qatar, so it was not exactly out of the ordinary for former president Nicolas Sarkozy to host a dinner with a member of the ruling Al Thani family, nor to invite Michel Platini, given the Qatari’s interest in sport, but the aftermath was positive for all involved, as Platini surprisingly voted for Qatar to host the 2022 World Cup, while PSG secured their much needed investment. Sarkozy, a well-known PSG fan, was described by French newspaper Libération as “the Qatari team’s 12th man”. Incidentally, Platini’s son now works for QSI.

PSG’s plans are very bold, as confirmed by Ancelotti, “I know PSG are not yet at the top level, but our objective is to reach the level of Chelsea, Manchester United, Barcelona and Real Madrid.” There is no doubt that PSG have become what Milan president Silvio Berlusconi described as “ a strong economic force”, but that is not a guarantee of immediate success. As an example, QSI need look no further than Manchester City, who took four years to win the Premier League following their Abu Dhabi takeover.

On a cautionary note, we should remember the old comment from opposing fans that PSG stands for Pas Sûr de Gagner. The club can indeed not be sure of winning, not least financially where it has little room for error in the FFP era, but, if nothing else, this will certainly be an exciting ride with the new signings bringing some much needed glamour to French football.