This has been a pretty good season for teams promoted from the Championship with Swansea City and Norwich City attracting many plaudits, so it is a little strange that Queens Park Rangers have not received much praise, especially as they actually won that division last year, playing some thrilling football en route to the title. In many ways, this is understandable, as they have been involved in a relegation battle for much of the season, but there’s more behind the lack of warmth than results on the pitch.

For many years, QPR were well regarded by neutrals, not least in the 70s when a team featuring the mercurial talents of Stan Bowles, Gerry Francis and Dave Thomas finished runners-up in the old First Division, only losing out to Liverpool by a single point. However, a succession of deeply unsuitable owners has tarnished the club’s image over the years, even alienating sections of its own support.

This season alone, the club’s long-suffering fans have already seen yet another change in ownership, as Malaysian entrepreneur Tony Fernandes took control in August. This was not the end of the moves, as Neil Warnock, the manager who took QPR into the Premier League for the first time in 15 years, was dismissed in January to be replaced by Mark Hughes, a man who notoriously questioned Fulham’s lack of ambition when he left them after less than 12 months.

"Mark of success?"

Although Hughes is an easy man to dislike, he did manage to save Blackburn Rovers from relegation when they found themselves in a similar predicament to QPR, and three successive home wins against Liverpool, Arsenal and Swansea have given hope that he can repeat the trick at Loftus Road.

One advantage that he will have compared to previous QPR managers is an owner that seems willing to support him, not just financially, as seen by the relatively high spending in the January transfer window, but by providing the stability that has been missing at the club for the best part of a decade.

The previous owners had also been welcomed into the club when they arrived in November 2007, as they saved QPR from “certain administration.” The consortium included some seriously affluent individuals: Flavio Briatore, Renault’s Formula One team principal (worth £150 million); Bernie Ecclestone, the F1 supremo (worth around £2 billion); and Lakshmi Mittal, the steel magnate (Britain’s richest resident, worth north of £20 billion).

The initial purchase price of less than £20 million must have seemed like small change to them. Briatore paid £540,000 for 54% (later selling a 20% stake to Mittal for £200,000), while Ecclestone’s 15% holding cost £150,000. In addition, they covered £13 million of debt and pledged £5 million in convertible loans to fund player purchases.

"England is mine and it owes me a living"

Although some believed that the acquisition would deliver untold riches, this was far from the case, as Ecclestone was quick to clarify, “QPR isn’t a wealthy club. It’s a club that’s owned by some wealthy people. No-one is going to be lashing out loads of money.” Unlike Roman Abramovich at Chelsea and Sheikh Mansour at Manchester City, the owners did not pour big money into the club, though in fairness they did bankroll some hefty losses.

Their motivation for buying into QPR was never clear. In fact, Ecclestone admitted that he first thought that Briatore was offering him an opportunity to invest in a restaurant. Mittal is thought to have invested in order to please his son-in-law, Amit Bhatia, a keen football fan, who took the family’s seat on the board of directors.

However, the new owners slowly went from heroes to villains, with fans giving Briatore and Ecclestone the wonderful nickname, “Tango and Cash.” All was revealed to the world at large in the amazingly candid documentary, “The Four Year Plan”, which in particular painted Briatore as an irritable buffoon prone to interfering in team selection and tactics.

"Briatore and Ecclestone - it takes two to tango"

As one caretaker manager, Gareth Ainsworth, diplomatically explained, “He’s the chief investor and he loves taking an active part in how his investment is going.” That’s one way of putting it. Briatore’s desire to get involved resulted in the club going through no fewer than six managers (plus two caretakers), most of whom he described as “idiots” in the documentary.

The club’s reputation as a laughing stock was “enhanced” by a series of embarrassing episodes: Briatore threatening to sell the club if he did not receive the names of thousands of fans that heckled him at one game; the sight of supermodel Naomi Campbell sporting a QPR scarf, while appearing bored stupid in the directors’ box; and the club’s traditional badge being replaced by a tacky new version. At one stage, Briatore’s status as a “fit and proper person” to own a football club was brought into question following the F1 ban for his part in “crashgate”, when he was accused of instructing one of his drivers to seek advantage for the team by deliberately crashing.

Even last season’s promotion party was soured when QPR were found guilty of fielding a player, Alejandro Faurlin, who was owned by a third party, which was strictly forbidden after the Carlos Tevez affair at West Ham. Fortunately, the club was only fined, instead of suffering a points deduction, but it reflected badly on management, especially the controversial chairman, Gianni Paladini.

"Faurlin - Don't cry for me, Argentina"

Fans were equally dismayed at the lack of funds provided for transfers with Warnock complaining that he had only been given £1.25 million to strengthen the squad, but they were incandescent with rage at the massive rise in ticket prices that followed the elevation to the Premier League, which seemed like a real slap in the face to people that had stuck with the club through thick and thin.

This was just one of the decisions that led to Bhatia’s departure, though he was also unhappy at the removal of his friend Ishan Saksena as chairman. In addition, the rejection of his bid to buy out the partners must also have played a part in his reasoning. This was a blow to the club, as he had been one of the few to emerge from the documentary with any credit.

However, even though the broadcast was cringeworthy, it is important to note that they did actually deliver on the primary objective, namely promotion to the Premier League within four years. In fact, without the money that Briatore and Ecclestone put in, it is possible that the club might not be here at all. As Warnock said, “When they came in, the club was in a mess. We shouldn’t forget that altogether.”

"Anton Ferdinand - he's not heavy, he's my brother"

The truth is that QPR had been in financial difficulties ever since their relegation from the Premiership in 1996, which meant that they missed out on the boom years in the world’s most lucrative domestic league and were hit by the collapse of ITV Digital.

The club went into administration in 2001 under music mogul Chris Wright as it dropped into the third tier and were only saved by a £10 million loan from the mysterious ABC Corporation, a company registered in Panama, though this came at a price, as the interest rate was a whopping 11.76%. The annual charges of more than a million were crippling for a club whose 2003 turnover was around £7 million. It was also surprising that the loan was so high, as Wright was only paid £3.5 million in full settlement for his loans.

The injection of cash did help QPR secure promotion back up to the second tier, but the sting in the tail was that the lenders were also given the option to acquire the stadium (used as collateral to secure the loan) for £10 million if the club failed to repay the debt, even though it was valued at more than twice that amount.

"Paladini - suits you, sir"

Our old friend Gianni Paladini arrived in 2005, when he introduced Antonio Caliendo, like him a former football agent. Although Caliendo’s reputation was hardly unblemished, having been convicted of corruption in Italy, the club somehow managed to keep its head above water, albeit hit by numerous scandals, such as the memorable court case when seven men were acquitted in a court case after Paladini had alleged that he had been threatened at gunpoint before a match against Sheffield United.

Nevertheless, Paladini’s services were retained by Briatore, proving that he was supremely adept at the art of survival, if nothing else. The finances remained unstable, as seen by the auditors comments in the 2009 accounts, which noted, “the existence of material uncertainties regarding the group’s ability to continue as a going concern… unless sufficient funding (was) forthcoming.”

This was not the first example of the auditors expressing concern, as the accounts published for the 2004/05 financial year had been shown to be different from those approved at the annual general meeting.

These were symptoms of QPR’s underlying financial problems, amply demonstrated by the club’s growing debt, which rose from £14 million in 2006 to £56 million in 2011, including £22 million in the last 12 months alone. This was largely funded by various loans from shareholders, including £15.8 million from Sarita Capital Investments (believed to be a Briatore vehicle), £12.3 million from Sea Dream Ltd (a company owned by the Mittal family), £11.4 million from Ecclestone; and £10 million from Amulya Property Ltd (a company connected to Briatore and Bhatia).

The Amulya loan replaced the infamous ABC loan “at a more favourable rate of interest”, though it is worth noting that the interest rate was still on the high side at 8.5%, before being extended in 2010 at zero interest. It also still gave the lenders the option to acquire Loftus Road on the cheap in certain circumstances. More positively, the other shareholder loans were all made at zero interest with both Ecclestone and Mittal advancing a further £10 million apiece in 2011.

QPR had also used £4.9 million of their £5 million overdraft facility with Lloyds Bank, while £2.1 million of the debt was unexplained. As a technical aside, the analysis of net debt in Note 24 of the 2011 accounts does not equal the figures listed in the Creditors Notes (15 and 16), either in total or the split between debt due within one year and after one year.

Of course, this is all largely irrelevant, as Tony Fernandes and his partners have since bought a majority shareholding (66%) in the club. The Mittal family retained a 33% stake and Amit Bhatia was brought back as vice-chairman.

"Wright-Phillips - chip off the old block"

The purchase, reportedly costing £45 million in total, included the re-assignment of the loans made by Briatore and Ecclestone to Tune QPR Sdn Bhd, a company controlled by Fernandes, and the repayment of the bank overdraft. This was nowhere near the £100 million that the previous owners had been seeking, but largely covered the money that they had put in.

Bhatia confirmed that the gruesome twosome were no longer involved with QPR, “They have no ties with the club left. Balance sheet, debt, amounts owed – all of it.” That included ownership of the stadium. The takeover also resulted in Paladini’s eight-year association with the club ending three months later.

New chief executive Philip Beard announced, “The reality is that the club has no debt”, but he must have meant that it had no external debt, as the shareholder loans have simply been taken on by the new owners.

"Fernandes - come fly with me"

The arrival of Fernandes hopefully heralds a new dawn. The affable founder of Air Asia and principal of the Lotus Formula One team has a good business record and has already been much more communicative with the fans than his predecessors, making good use of his Twitter account. Although perceived as a nice guy, he is not afraid of taking tough decisions, hence his replacement of Warnock with a man he considered more likely to avoid the dreaded drop.

That said, QPR fans should not be expecting Fernandes to be a benefactor like Abramovich or Mansour, as he said, “I’m not someone who can whip out the cheque book like them. That’s Disneyland stuff. I’m not a sugar daddy. Maybe a sugar baby.” He continued, “This is not a black hole of Calcutta or a trophy asset. This has to be run as a business.” That might sound like pie in the sky, but he likened the situation in football to his other sporting experience, “I got into Formula One when the cost cutting came in. And you know, crazy budgets were slashed into much, real profits.”

The extent of his immediate ambition is to survive in the Premier League, which he deemed “realistic”. Bhatia added that they needed to achieve this aim “without throwing large amounts of money at it.”

This all sounds rather admirable, but Briatore said much the same thing after his arrival, “These deals will allow QPR to move towards our objective of ensuring that QPR is financially self-sufficient”, which was subsequently followed by three years of considerable losses.

This culminated in a deeply worrying £25.4 million loss in 2011 (in QPR Holdings Limited), which was £11.7 million (85%) higher than the previous year’s £13.7 million deficit, meaning that the club lost nearly £500,000 a week. It actually would have been £2 million worse without the reinstatement of a provision for a liability that was in place due to the sale of the club to a previous owner.

Unlike many clubs, the figures are not really impacted by profits on player sales, which were only £0.5 million last year. Indeed, the highest recorded in the last six years was only £2.1 million in 2008, largely as a result of the sale of Lee Cook to Fulham.

Clearly, these accounts are the last before the Fernandes takeover, so next year’s figures will be very different. In particular, promotion to the Premier League will mean significantly higher revenue (and expenses).

There’s certainly room for improvement, as it is ages since QPR achieved break-even. The losses really exploded in the Briatore/Ecclestone era with £58 million being racked up in the last three years alone. Even the relatively small 2008 loss of £6 million was artificially boosted by Caliendo waiving £4 million of his outstanding loans. Excluding this once-off factor, there would have been another double-digit loss in 2008 of £10 million. In fact, excluding all exceptional items, the total loss under the previous owners amounted to a colossal £70 million in four colourful years.

Of course, the vast majority of clubs in the Championship lose money with only three of the 24 contenders making money in 2010/11 (Watford, Scunthorpe United and Leeds United) and nine losing more than £10 million. This is partly a result of low TV money in England’s second tier, but also due to many clubs over-spending in order to reach the promised land of the Premier League.

QPR obviously managed to clear this hurdle, but their £25 million loss was by far the biggest in the Championship. As a comparison, Norwich City and Swansea City were also promoted, but made much smaller losses, £7 million and £11 million respectively.

The reason for QPR’s huge loss is blindingly obvious if we look at the factors behind their worsening deficit in the last five years, when the loss widened by £22 million from £3 million in 2006 to £25 million in 2011. In this period, revenue only grew by £7 million, but wages surged by £23 million. Other costs (£6 million) and player amortisation (£3 million) also increased, but the real damage was done by the booming wage bill.

Although QPR’s revenue grew 13% in 2011 from £14.4 million to £16.2 million, this was only mid-table in terms of the Championship. Leeds United were top of the tree with £33 million, due to very high gate receipts (thanks to Ken Bates’ ticketing policy) and a prosperous commercial operation. The next three clubs in the revenue league (Burnley, Middlesbrough and Hull City) all benefited from £15 million parachute payments after relegation from the Premier League.

Based purely on revenue levels, QPR did well to secure promotion, though Swansea’s achievement in doing the same on turnover of less than £12 million is even more remarkable.

One area where Briatore and Ecclestone should be applauded is the new commercial deals that they negotiated in 2009, which increased revenue by 60% from £9.2 million to £14.8 million. Even that pales into insignificance compared to the growth this season in the Premier League, when I estimate revenue will rise around 240% to £55 million, almost entirely due to the TV deal which should deliver at least £40 million on its own.

Unhelpfully, QPR stopped providing an analysis of their revenue after the 2008 annual report, so I have estimated the split since then using various assumptions. The accounts inform us that ticketing was 34% of total revenue in 2010 (42% in 2009), which would give £4.9 million match day revenue. Strangely, the same accounts also state that match day revenue is £2.5 million in the Business Review, but this seems very low. However, I have used the increment for this figure in the 2011 accounts of £0.4 million (£2.9 million less £2.5 million) as the basis for 2011 match day income of £5.3 million. This year assumes a 25% increase in the top flight.

The TV revenue is mainly per the distributions made to all clubs in the Championship, e.g. in 2010 this was £3.8 million, comprising central distribution of £2.5 million plus a £1.3 million solidarity payment from the Premier League. In 2011 this increase to £5.2 million, as the solidarity payment rose to £2.2 million and each club was given an additional £0.5 million as their share of the parachute payments for Newcastle and WBA, because they went straight back up to the top tier. The remaining TV money is for live broadcasts and progress in the cup competitions.

That just leaves commercial income as the balancing figure in years 2009 to 2011 with 2012 growth in the Premier League estimated at 25%, which does not seem unreasonable.

Of course, this season is all about the revenue from the Premier League’s TV deal. Many people refer to promotion being worth around £90 million, which is a little misleading, as it is not all received in one fell swoop, but it’s still a magnificent prize. Even if QPR do come straight back down, they would receive £40 million TV income plus £48 million parachute payments over the next four years (£16 million in each of the first two years, and £8 million in each of years three and four) plus additional gate receipts and commercial revenue.

Furthermore, if Rangers finish higher in the Premier League, they would receive even more TV money with every season survived adding another £40+ million to the coffers. Given the spectacular difference in revenue compared to the Championship, it is understandable why clubs like QPR push themselves to the absolute limit to secure promotion, though it’s a dangerous game, as only three clubs go up every year, leaving another 21 disappointed.

One concern is that the club might eat into that higher revenue by increasing wages and other costs, but the net effect is still likely to be positive. If we look at the three teams that were promoted to the Premier League in 2009/10, we can observe this phenomenon with Newcastle United, WBA and Blackpool, as all three clubs dramatically improved their operating profitability, even though wages increased.

Although £55 million revenue must seem like a huge sum to QPR, after averaging around £15 million for the last three years, it is still relatively low in the Premier League, e.g. only Blackpool and Wigan Athletic generated less revenue last season. For some perspective, QPR’s recent defeat to Manchester United was against a team whose £331 million revenue is six times as much as their own. As Sky used to say, “it’s a different ball game.”

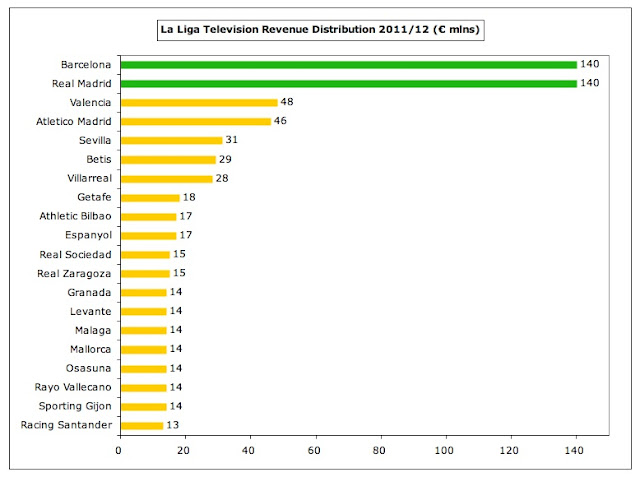

Nevertheless, the allocation of TV money is reasonably equitable, ranging from £40 million to £60 million, with 50% of the domestic rights (£13.8 million) and 100% of the overseas rights (£17.9 million) shared out equally. Facility fees are allocated based on the number of matches shown live on TV (minimum of ten for each club), while the merit payment is worth £757,000 for each place.

Match day revenue of around £5 million is QPR’s real Achilles Heel. Clubs like Manchester United and Arsenal generate more revenue in just two games than QPR achieve in a whole season. This is partly down to Rangers’ low crowds with last season’s average attendance of 15,635 being only the 14th highest in the Championship.

This actually represented something of a recovery, as the previous season the average had only been 13,349. In fact, during the darkest days QPR’s crowds fell below 13,000. Although attendances have increased this season to over 17,000, this is still the smallest in the Premier League, even behind Wigan Athletic, whose crowds are notoriously low.

Part of the problem is the capacity at Loftus Road, which is only 18,360. This was one reason why QPR raised their prices so much following promotion, as the lovable Paladini explained, “QPR is a small ground, so we could not survive if we did not put prices up.” However, this did not make much sense, given the relatively small sums involved, especially as this increase understandably caused so much ill will among the supporters.

Season ticket prices were raised by around 40%, but the real increase was even higher, as there are four fewer matches in the Premier League, while match day prices doubled. This was the ghastly result of Briatore’s desire to create a “boutique stadium.” In fairness, most promoted teams do increase ticket prices, but this was excessive.

At least it presented Tony Fernandes with a PR open goal and he duly thumped the ball into the back of the net by quickly revising the pricing structure, so season ticket holders were given “significant” refunds; a cheaper match day pricing category was introduced; and under-eights were allowed in free of charge if accompanied by an adult.

Although Loftus Road can be an intimidating arena for visiting teams, it is far from ideal for a club with aspirations of competing at the top level. Given the current ground’s proximity to nearby housing, it would be too difficult to expand it, so a move to a new stadium has been mooted. Although it is not clear how this would be funded, Fernandes seems enthused by the idea and Philip Beard has emphasised its importance, “Football will be the bedrock of that stadium and a place where we can generate additional revenues from other activities so that the business plan for the club is sustainable.”

The club would like to stay close to where they are, as Fernandes explained, “It makes no sense to move out from where the fan base is.” Aided by the possibilities opened up by the BBC’s relocation to Salford and the massive Westfield shopping development, the club has reportedly identified three possible sites in the White City area.

However, the obvious question is whether Rangers would be able to fill a new stadium. Fernandes’ “gut feel” is for a 40,000 to 45,000 capacity, even though that would be more than twice the current attendance. That’s a big ask, especially with so many other teams on the doorstep.

"Running up that Hill"

Some of the costs might be reduced with a ground share, especially as QPR have plenty of previous here. Not only did Fulham share Loftus Road for two seasons between 2002 and 2004 while Craven Cottage was being redeveloped, but Wasps rugby union club also played home matches there for a while.

QPR’s commercial income of £5-6 million is not too bad, comparing favourably with many established top flight clubs like Bolton Wanderers and Blackburn Rovers, though it is only half of the £12 million generated by neighbours Fulham. Indeed, the club has stated that it “believes that its Premier League status will help it to significantly increase its commercial revenue.”

The previous owners had already demonstrated commercial acumen by making once-off payments in 2008 to extricate themselves from “poor value” sponsorship agreements with Car Giant and Le Coq Sportif. These were replaced by a three-year deal with Gulf Air worth £2.3 million a season and a five-year kit supplier agreement with Lotto Italia worth £20 million, which was a record for the Championship, though the full value would only be attained with promotion to the Premier League.

Last summer a joint shirt sponsorship deal was signed with Malaysian Airlines for the home kit and Air Asia for the away kit and third jersey for the next two years. The value was not divulged beyond a “multi-million pound deal”, though the respected Sporting Intelligence website estimated £2.3 million a year in line with the previous sponsor, while the Malaysian press estimated that it could be as much as £3 million. Beard said that “attracting two major Asian companies to come on board shows the global appeal QPR has as a brand”, though his argument is weakened by the fact they are both part-owned by Fernandes.

In any case, the money is not too bad at all, though it is still a fair bit less than the £20 million earned by Liverpool from Standard Chartered, Manchester United from Aon and (reportedly) Manchester City from Etihad. If the £4 million a season for the kit supplier are accurate, that’s even more impressive, e.g. it would be higher than Aston Villa’s new deal with Macron, but again it is small beer compared to the £25 million deals for Liverpool with Warrior Sports and Manchester United with Nike.

Of course, the burning issue at QPR has been the wage bill, which has more than quadrupled in the last five years, rising from £6.3 million in 2006 to £29.7 million in 2011. This has resulted in a dreadful wages to turnover ratio of 183%, significantly higher than UEFA’s recommend upper limit of 70%. To place that into context, big spending Manchester City’s ratio is “only” 114%.

In fact, QPR’s ratio has been above 100% in each of the last four years, which they partly ascribe to the imposition of transfer windows, claiming that this means they have to recruit a larger squad. In addition, the figures have been inflated by numerous termination payments to former managers.

While the wage bill looks awful, a couple of points should be acknowledged: (a) the 2011 figures have been inflated by bonus payments for promotion; (b) this is far from unusual in the Championship, where nearly half the clubs have a wages to turnover ratio over 100%.

Nevertheless, QPR’s wage bill of £29.7 million was easily the highest in the Championship last season (having pro-rated Middlesbrough’s figures, as their last accounts covered 18 months). Only three clubs in that division had a wage bill over £20 million, while QPR’s payroll was £11-12 million higher than the other two promoted clubs. Put another way, it was almost twice as much as clubs like Leicester City, Nottingham Forest and Leeds United.

However, before we stray too much into “shock, horror” territory, it was still a lot lower than every Premier League club in 2010/11 with the exception of Blackpool. Clearly, the wage bill will have increased this season with the likes of Joey Barton, Djibril Cissé and Nedum Onuoha being recruited on £60-80,000 a week, but this is unfortunately the price of dining at the top table. As the 2001 accounts put it, “The Group operates in a highly competitive market for talent and the market rate for transfers and wages is, to a varying degree, dictated by competitors.”

The other expense impacted by investment in the squad is player amortisation, which has been on the rise, but only reached £3.2 million in 2011. For those unfamiliar with this concept, amortisation is simply the annual cost of writing-down a player’s purchase price, e.g. Shaun Wright-Phillips was signed for around £6 million on a 3-year contract, but his transfer will only be reflected in the profit and loss account via amortisation, booked evenly over the life of his contract, so £2 million a year (£6 million divided by 3 years).

In this way, amortisation will rise significantly in the next couple of seasons in line with the recent higher expenditure in the transfer market. That said, QPR will still have a long way to go to match Manchester City’s £84 million.

Over the years, QPR have hardly been big spenders. Indeed, they had net sales proceeds of £1.2 million in the five years up to 2007. Only £14.8 million was spent during the four years under Briatore, as the club largely relied on free transfers and loans. Even in the promotion season, Warnock’s net spend was just £1.5 million.

However, things have changed since Fernandes’ arrival with £20.6 million being splashed out in the last two transfer windows, including £11 million in January alone on Bobby Zamora, Cissé and Onuoha plus loans for Samba Diakité, Federico Macheda and Taye Taiwo.

As the Malaysian said, “We have made a significant investment in relation to bringing new players to QPR.” In fact, only four clubs have spent more in that period (Chelsea, Manchester City, Manchester United and Liverpool), though Fernandes was at pains to emphasise that they had only been spent as much as “half a Man City player.” To an extent, the expenditure is predictable, as explained by Beard, “We are new to the Premier League. To stay up, we have had to invest in the squad.”

QPR’s balance sheet is not very robust with net liabilities of £40 million, having enjoyed net assets up to 2006 (as high as £10 million in 2000), though player values are under-stated in the books at £8 million, when their worth in the real world is much higher. The Transfermarkt website estimates the current value to be £70 million, taking into consideration the recent influx.

This deficit explains the need for support from the club’s shareholders and creditors, which is further demonstrated by the cash flow statement. In the last four years, this shows net cash outflow from operating activities of £47 million, rising to £68 million after interest payments and investment in players and infrastructure. This deficit required £64 million of new financing, made up of £30 million additional share capital and £34 million new loans.

It is therefore crucial that Fernandes and Mittal continue to provide support. Some concern has been expressed over the fact that Fernandes is not a QPR fan (he supports West Ham), though he did actually grow up in the area. Mittal could be seen as a somewhat reluctant owner, but Beard’s understanding is that the shareholders are “100% committed to this club in the short, medium and long term.” Bhatia has also said that his family “remains passionate about QPR.”

In any case, Fernandes has explained that apart from the emotional pull of owning a football club, he was also attracted by good, old-fashioned business reasons, especially QPR’s strength as a marketing vehicle for his companies. “Many people do not realise the power of sport to market a brand,” he said. “You can spend £40 million on advertising and have nothing like the same effect. Around the world, everybody watches Premier League football.”

Fernandes even believes that QPR could be profitable one day: “Yes, without a doubt. Otherwise I wouldn’t have got involved.” That makes sense, as he is reportedly worth “only” £200 million, which is big money for the likes of you and me, but does not go very far in high-level football. This is why he is so committed to the idea of the club finally paying its own way. As he neatly summarised, “It can’t be about one benefactor. I might be hit by a bus.”

"Shaun Derry - All cats are grey"

In the long-term, there are ambitious plans to build a new training ground, which would help improve the youth system. Fernandes said, “I’m keen to create a good academy, so that there’s a constant supply of players. We’re in a fantastic part of London and we should be bringing kids through.”

More immediately, the objective is clear, “The main thing is to avoid relegation.” Even though the blow would be softened by parachute payments, there would still be a tremendous financial hit, especially as it is rumoured that some top earners do not have relegation clauses in their contracts. Older fans would need no reminding that the last time that happened it took 15 years for QPR to get back...

Maintaining Premier League status for a couple of seasons would also provide some badly needed stability at the club, which might just loosen Mittal’s purse strings. Even if not, it would make QPR a more attractive opportunity for other investors.

"That's Zamora"

QPR fans have endured enough drama to last a lifetime, but there is potential here, especially under the guidance of Fernandes, who achieved a spectacular turnaround with Air Asia. When he bought that company, it was “a kind of unpolished diamond” with just two planes and a lot of debt, but he transformed it into a success story with 100 aircraft and profits of $400 million.

Could he achieve something similar at QPR? History would suggest not, but Fernandes has already beaten the odds once in his career, so it’s not impossible that West London’s version of Hoop Dreams could become reality. Westway to the World? Time will tell.