So, why does Snap present itself as a camera company? I think that the answer lies in the social media business, as it stands today, and how entrants either carve a niche for themselves or get labeled as me-too companies. Facebook, notwithstanding the additions of Instagram and WhatsApp, is fundamentally a platform for posting to friends, LinkedIn is a your place for business networking, Twitter is where you go if you want to reach lots of people quickly with short messages or news and Snap, as I see it, is trying to position itself as the social media platform built around visual images (photos and video). The question of whether this positioning will work, especially given Facebook's investments in Instagram and new entrants into the market, is central to what value you will attach to Snap.

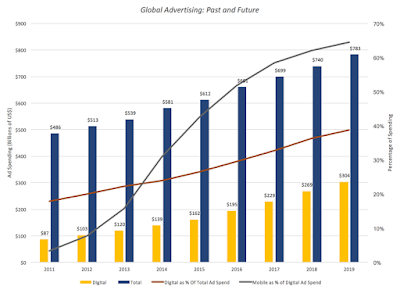

- It is a big market, growing and tilting to mobile: The digital online advertising market is growing, mostly at the expense of conventional advertising (newspapers, TV, billboards) etc. You can see this in the graph below, where I plot total advertising expenditures each year and the portion that is online advertising for 2011-2016 and with forecasted values for 2017-2019. In 2016, the digital ad market generated revenues globally of close to $200 billion, up from about $100 billion in 2012, and these revenues are expected to climb to over $300 billion in 2020. As a percent of total ad spending of $660 billion in 2016, digital advertising accounted for about 30% and is expected to account for almost 40% in 2020. The mobile portion of digital advertising is also increasing, claiming from about 3.45% of digital ad spending to about half of all ad spending in 2016, with the expectation that it will account for almost two thirds of all digital advertising in 2020.

Sources: Multiple - With two giant players: There are two dominant players in the market, Google with its search engine and Facebook with its social media platforms. These two companies together control about 43% of the overall market, as you can see in this pie chart: If you are a small player in the US market, the even scarier statistic is that these two giants are taking an even larger percentage of new online advertising than their historical share. In 2015 and 2016, for instance, Google and Facebook accounted for about two-thirds of the growth in the digital ad market. Put simply, these two companies are big and getting bigger and relentlessly aggressive about going after smaller competitors.

|

| Link to my book |

| Snap | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPO date | 19-Aug-04 | 19-May-11 | 18-May-12 | 7-Nov-13 | NA |

| Revenues | $1,466 | $161 | $3,711 | $449 | $405 |

| Operating Income | $326 | $13 | $1,756 | $(93) | $(521) |

| Net Income | $143 | $2 | $668 | $(99) | $(515) |

| Number of Users | NA | 80.6 | 845 | 218 | 161 |

| User minutes per day (January 2017) | 50 (Includes YouTube) | NA | 50 | 2 | 25 |

| Market Capitalization on offering date | $23,000 | $9,000 | $81,000 | $18,000 | ? |

| Link to Prospectus (from IPO date) | Link | Link | Link | Link | Link |

- Snap will remain focused on online advertising: I believe that Snap's revenues will continue to come entirely or predominantly from advertising. Thus, the payoff to Spectacles or any other hardware offered by the company will be in more advertising for the company.

- Marketing to younger, tech-savvy users: Snap's platform, with its emphasis on the visual and the temporary, will remain more attractive to younger users. Rather than dilute the platform to go after the bigger market, Snap will create offerings to increase its hold on the youth segment of the market.

Source: The Economist - With an emphasis on user intensity over users: Snap's prospectus and public utterances by its founders emphasize user intensity more than the number of users, in contrast to earlier social media companies. This emphasis is backed up by the company's actions: the new features that it has added, like stories and geofilters, seem designed more to increase how much time users spend in the app than on getting new users. Some of that shift in emphasis reflects changes in how investors perceive social media companies, perhaps sobered by Twitter's failure to convert large user numbers into profits, and some of it is in Snap's business model, where adding users is not costless (since it has to pay for server space).

To complete the valuation, there are two other details that relate to the IPO.

- Share count: For an IPO, share count can be tricky, and especially so for a young tech company with multiple claims on equity in the form of options and restricted stock issues. Looking through the prospectus and adding up the shares outstanding on all three classes of shares, including shares set aside for restricted stock issues and assorted purposes, I get a total of 1,243.10 million shares outstanding in the company. In addition, I estimate that there are 44.90 million options outstanding in the company, with an average exercise price of $2.33 and an assumed maturity of 3 years.

- IPO Proceeds: This is a factor specific to IPOs and reflect the fact that cash is raised by the company on the offering date. If that cash is retained by the company, it adds to the value of the company (a version of post-money valuation). In the case of Snap, it is estimated that roughly $3 billion in cash from the offering that will be held by the company, to cover costs like the $2 billion that Snap has contracted to pay Google for cloud space for the next five years.

|

| Download spreadsheet |

|

| Snap Simulation Details |

- The numbers at the high end of the spectrum reflect a pathway for Snap that I call the Facebook Light story, where it emerges as a serious contender to Facebook in terms of time that users spend on its platform, but with a smaller user base. That leads to revenues of close to $25 billion by 2027, an operating margin of 40% for the company and a value for the equity of $48 billion.

- The numbers at the other end of the spectrum capture a darker version of the story, that I label Twitter Redux, where user growth slows, user intensity comes under stress and advertising lags expectations. In this variant, Snap will have trouble getting pushing revenue growth past 35%, settling for about $4 billion in revenues in 2027, is able to improve its margin to only 10% in steady state, yielding a value of equity of about $4 billion.

As I finish this post, I notice this news story from this morning that suggests that bankers have arrived at an offering price, yielding a pricing for the company of $18.5 billion to $21.5 billion for the company, about $4 billion above my estimate. So, how do I explain the difference between my valuation and this pricing? First, I have never felt the urge to explain what other people pay for a stock, since it is a free market and investors make their own judgments. Second, and this is keeping with a theme that I have promoted repeatedly in my posts, bankers don't value companies; they price them! If you are missing the contrast between value and price, you are welcome to read this piece that I have on the topic, but simply put, your job in pricing is not to assess the fair value of a company but to decide what investors will pay for the company today. The former is determined by cash flows, growth and risk, i.e., the inputs that I have grappled with in my story and valuation, and the latter is set by what investors are paying for other companies in the space. After all, if investors are willing to attach a pricing of $12 billion to Twitter, a social media company seeming incapable of translating potential to profits, and Microsoft is paying $26 billion for LinkedIn, another social media company whose grasp exceeded its reach, why should they not pay $20 billion for Snap, a company with vastly greater user engagement than either LinkedIn or Twitter? With pricing, everything is relative and Snap may be a bargain at $20 billion to a trader.

YouTube Video

Link to book

Attachments